In 1945, the North Pole was a powerful global symbol. It’s even more potent today.

ANALYSIS: In the wake of World War II, the newly formed United Nations put the North Pole at the center of its flag. Today the pole is an even more powerful symbol of humanity's shared fate.

(Dermot Cole)

NEW YORK — The Uber driver slid onto Columbus Avenue, where not a single moving car blocked our path on a street that normally sees about 1,300 cars at lunch hour.

On Jan. 4, the day the “bomb cyclone” hit New York City, my brother and I had to cross from the Upper West Side to Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital for his chemo treatment.

Something about this felt like a winter day at home in Alaska. The snow fell hard and fast, hiding all evidence of the concrete canyons, shrinking the field of view so much that it seemed we could have been on a deserted country road.

Millions of New Yorkers had heeded the advice to stay off the streets that day because of the storm of the century. My brother said something about how quiet everything seemed.

No angry drivers exercised their horn fingers, blasting other idiots to get the hell out of the way. A foot of snow and 30 mph winds provided a chill pill to the city that never sleeps.

For a few days, every time I watched the news on TV, read a newspaper or checked the headlines, I learned that it was warmer in Alaska than New York, Boston, Houston, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Jacksonville, or fill in the blank. Every place was colder than Alaska, which led to discussions about climate change and the

Arctic and what that means for the world.

Yes, isolated weather events and not the same as climate, but climate is nothing more than a longterm weather pattern. Are the bomb cyclone and the polar vortex evidence of climate change? Yes and no, the experts say.

The rapid increase in the Arctic means that the difference with areas farther south is smaller than it once was, redirecting the jet stream with significant consequences. The full story is yet to be written, but only fools claim that the mountain of evidence compiled so far is irrelevant.

We couldn’t see the names and numbers on buildings as the snow fell that day, which is why the driver let us off a couple of blocks past the hospital entrance. I was glad I had my winter parka on and the hood up as we trudged through the bomb cyclone.

The weather led to a brainstorming session with my brother, a history professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, about plans to start this column in Arctic Today, a site dedicated to a comprehensive look at the region.

I have been writing about Alaska for many decades, usually for a local audience.

The first thing he said was how I should take a look at the flag of the United Nations, which is a view of the world with the North Pole in the center, flanked by two olive branches.

A few days later I made my way to the Lower East Side for inspiration on another cold day.

I walked past the Trump World Tower, which has 90 floors on its elevator displays, but only 72 floors inside. With some people, things are never what they seem.

There is more coherent thinking in the complex of buildings across the street that houses the United Nations. Despite the institution’s failings, it remains our best hope for the future in a world where no one goes it alone.

Admission to the UN today is far more complicated than a half-century ago when I visited as a high school student. I picked up a visitor pass, had my picture taken by security guards across the street and then crossed over for a screening process familiar to anyone who goes to an airport.

The UN emblem is everywhere on the premises, from the water bottles and notebooks in the gift shop to a display just inside the main reception area. Two blue-and-white UN flags posted there are battered and somewhat the worse for wear, poignant reminders of service by those who work to relieve suffering and promote peace.

One of the flags, which has a big tear where Asia should be, got that way from a bomb blast in Baghdad 15 years ago that killed 22 UN workers and injured many more.

On the other side of the hall, another flag under glass once flew in Port-au-Prince until the 2010 earthquake and tsunami killed hundreds of thousands in Haiti. Among the dead were 102 United Nations workers, who came from 29 countries.

The flag design came about as nations gathered near the end of World War II in search of a symbol to embody dreams of a lasting peace.

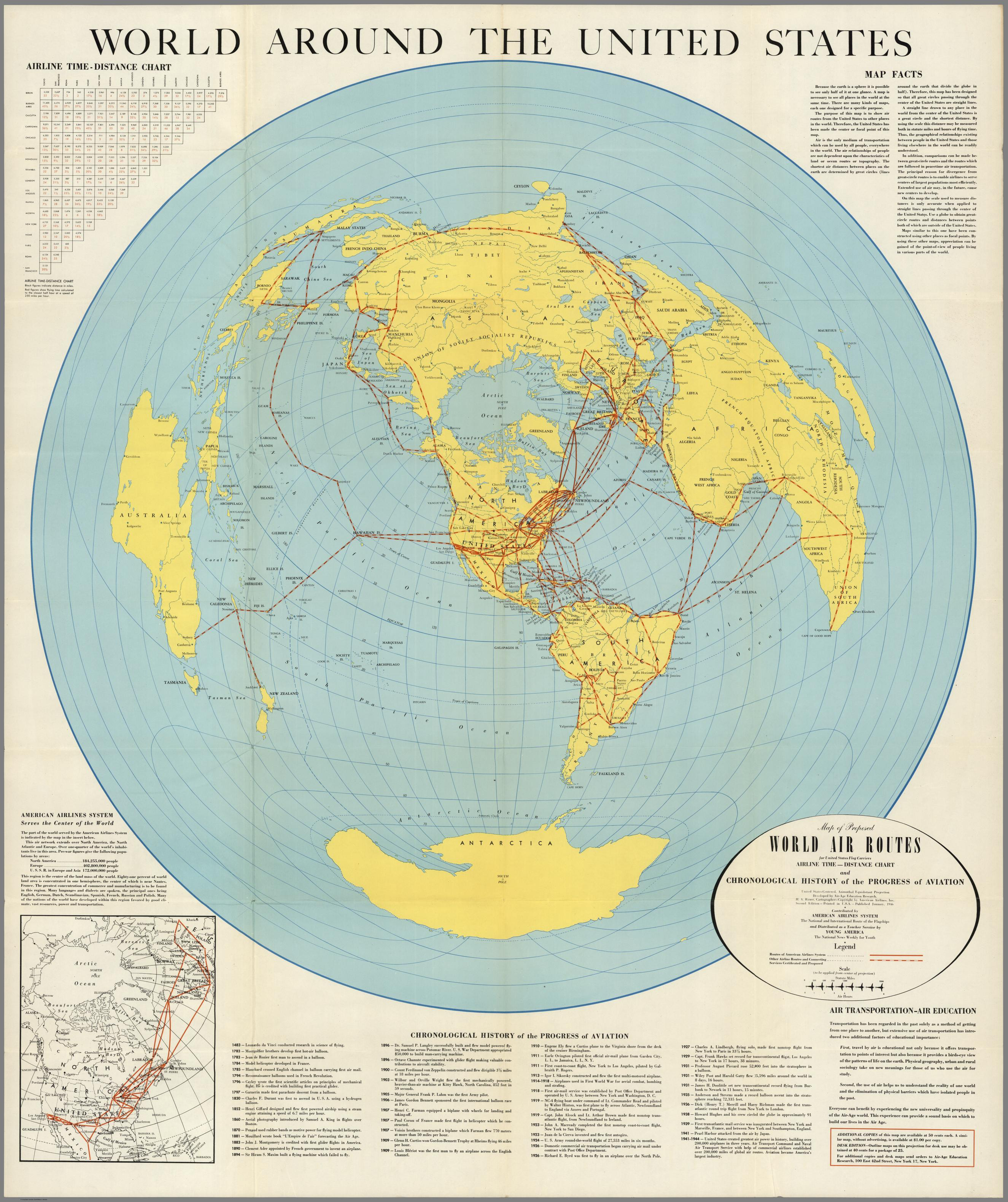

They settled on the “azimuthal equidistant” map that puts the North Pole at the center, an approach to geography that had its roots in the technology of war and peace.

“We were doing charts for air distances for bombing and wherever you went had to be approached via the North Pole,” wrote Donal McLaughlin, chief of graphics for the Office of Strategic Services, a predecessor of the CIA.

As one map expert put it, “The world created by the airplane can best be shown on a map which radiates outward from the North Pole.”

McLaughlin sketched a lapel pin with a polar projection and with some changes it became the UN emblem and the UN flag.

The early design had New York at the lower center with a vertical axis to the North Pole., but later the angle was shifted so that the prime meridian and the international dateline became the center. This had the effect of turning Alaska to the side, at least in the way we are accustomed to imagining the world.

The revised version added Chile, Argentina and New Zealand and also turned the world “so that the map didn’t look upside down to the Soviets,“ McLaughlin wrote. This compromise placed the U.S. on one side, Russia on the other and the North Pole at the center.

If that was a powerful symbol when the nations of the world gathered in 1945 to try to work together, it is much more so today with the rapid changes taking place in the Arctic that solidify the North Pole as a central point, even as the summer ice dwindles, opening the way for new transportation and communication links.

Many nations cross paths in the Arctic, a region where cooperation and understanding is crucial as its world image evolves from “frozen wasteland” to one of the crossroads of the globe.

The rise of the Internet and the development of satellite technology have so enhanced the flow of information and the gathering of scientific data that we can now see the Arctic in ways that were never possible.

The Arctic, once thought to be on the fringes of human existence, has moved to the center of the world with the rise of air power and telecommunications.

Humans are waking up again to this reality now that the ice is melting and control of the ocean is an opportunity for cooperation or confrontation.

I though about all of this as we returned to Alaska, which had been warmer than New York for days.

In this column I’ll examine some of the key political, social and economic developments in Alaska and elsewhere in the Arctic, trying to put them in context as best as I can.

The changes taking place in this region stand to reshape the world in ways that will make the one-day drama of the bomb cyclone fade into insignificance.

Dermot Cole, a veteran Alaska newspaper columnist and author, lives in Fairbanks, Alaska. For more of his writing about Alaska politics and life in the far north, see his Reporting from Alaska blog, at dermotcole.com.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by Arctic Today, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary (at) arctictoday.com.