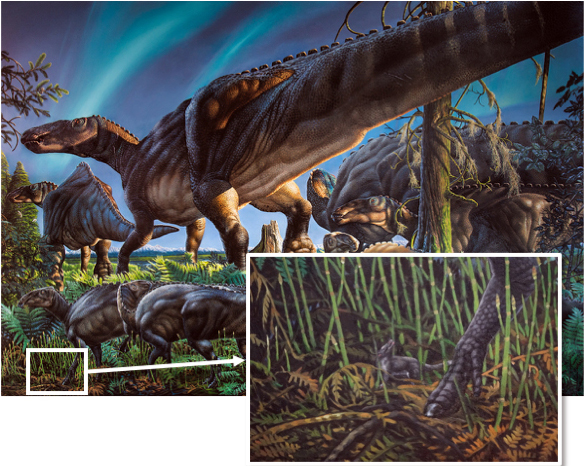

70 million years ago dinosaurs and — a tiny marsupial — called the Arctic home

The marsupial, about the size of a human thumb, is the northernmost marsupial ever discovered.

We don’t think of the Arctic as a former home of dinosaurs any more than we think of it as a former home of distant relatives to the kangaroo and other marsupials.

But the fossil evidence for a distinct group of dinosaurs that thrived above the Arctic Circle is growing stronger by the year and now the remains of a tiny marsupial have been found in northern Alaska, according to authors of a study published last month in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

Most marsupials, of which there are about 330 living species, are found in the Southern Hemisphere.

But that hasn’t always been true.

A new fossil discovery shows a marsupial lived in Alaska’s Arctic nearly 70 million years ago, co-existing with dinosaurs.

The evidence for the existence of a tiny creature dubbed “Unnuakomys hutchisoni,” the northernmost marsupial ever discovered, has been found on a bluff in northern Alaska.

The name Unnuakomys hutchisoni was created by blending the Iñupiaq word for “night,” the Greek word for mouse and the surname of J. Howard Hutchison, a paleontologist who discovered the fossil-rich site.

The “night mouse” had to survive at least four months a year in darkness, probably feeding on insects and small plants.

“This new marsupial is an exciting addition to the growing list of new species of dinosaurs and other animals that we are describing from northern Alaska as part of a bigger project to reveal ancient Arctic ecosystems,” study coauthor Patrick Druckenmiller of the University of Alaska Fairbanks said in an announcement.

Like the Arctic dinosaurs, which developed in isolation and lived nowhere else, the marsupial was probably limited to this region. It probably weighed less than an ounce, was smaller than a human thumb and could have survived winters underground.

We know of its existence because of about 60 fossilized teeth, each about the size of a grain of sand, were found by a painstaking process of looking at ancient river sediments under a microscope.

The teeth, with each species having its own unique markers, were the key to the discovery and identification of the animal.

Pediomys Point is a deposit that ranges from 2 to 15 centimeters in thickness and contains small mammal and dinosaur teeth, about half a millimeter maximum size, and bones up to 10 centimeters long.

Scientists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the University of Colorado pieced together the story of this tiny creature from evidence contained in what is known as the Prince Creek Formation.

More than three decades ago, dinosaurs fossils were first discovered in the geologic formation and ever since paleontologists have been building a more complete portrait of what it was like during the late Cretaceous period.

The site is at 70 degrees North today, but it may have been as far north as 80-85 degrees 70 million years ago, about where the northern edge of Greenland is.

“As the first mammal to be described from the Prince Creek Formation, Unnuakomys hutchisoni indicates the Arctic also hosted at least one endemic species of mammal,” Druckenmiller and five other researchers wrote in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology Feb. 14.

They said that when considered along with discoveries of novel animals from fossils in East Sibieria, there is growing evidence that the evolution of unique species were the rule, rather than the exception in the Cretaceous Arctic.

“Northern Alaska was not only inhabited by a wide variety of dinosaurs, but in fact we’re finding there were also new species of mammals that helped to fill out the ecology,” Druckenmiller, the director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North, said in an announcement. “With every new species, we paint a new picture of this ancient polar landscape.”