A breakthrough in an Alaska cold-case murder shines a light on violence against Indigenous women in the Arctic

Indigenous women and girls face high rates of violence across Alaska. New legislation could begin to address the problem.

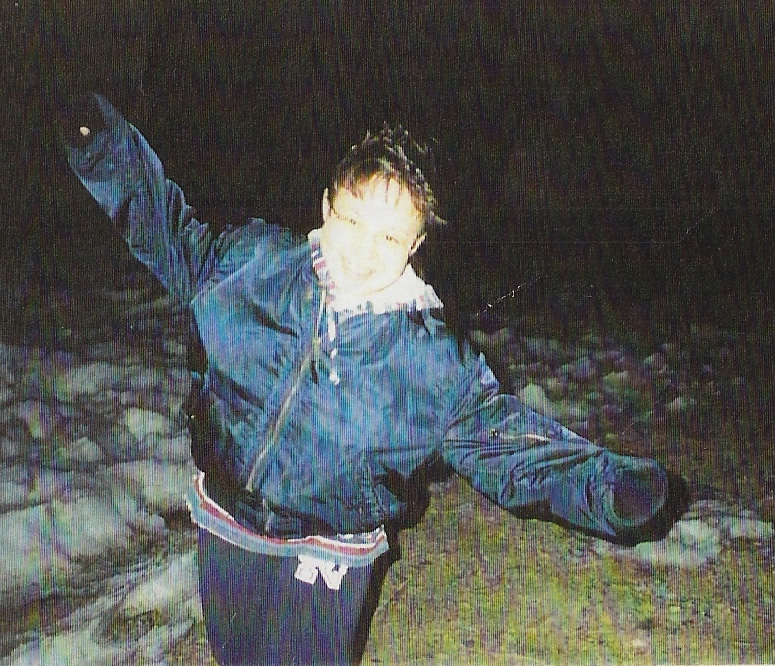

On April 26, 1993, the body of a young woman was found in a bathroom at University of Alaska-Fairbanks. Sophie Sergie, a 20-year-old Yupik woman from Pitkas Point, had been raped and killed. She was visiting friends in their dorm, Bartlett Hall, at the university where she’d been enrolled before taking time off to earn money for orthodontic work.

She was last seen around midnight, when she left her friends to smoke a cigarette. Her body was found in a bathtub the following day.

Her assailant’s trail quickly went cold, and the case remained unsolved for more than 25 years. Until last week.

On February 15, Alaska state troopers announced they had arrested and charged a suspect in the case: Steven H. Downs, 44, of Auburn, Maine.

Inspired by investigators on the Golden State Killer case last year, Alaska’s police had turned to a genealogical database to find leads. Parabon Nanolabs, a company based in Virginia, used a DNA sample found on the crime scene to conduct genetic genealogy research. They were able to identify a likely relative of the suspect — Steven Downs’ aunt.

After the genetic lead, cold-case detectives continued to investigate. Downs was an 18-year-old UAF student who lived in Bartlett Hall at the time of the killing. Investigators had learned in 2009 that Downs owned a handgun similar to the weapon used in Sergie’s murder, although their findings were not conclusive enough to charge a suspect at the time.

Last week, detectives collected a DNA sample from Downs, which matched to the sample found on Sergie’s body. The detectives worked with Maine authorities to take Downs into custody, and he will be extradited to Alaska to face charges related to the sexual assault and murder of Sophie Sergie.

“While an arrest doesn’t bring Sophie back, we are relieved to provide this closure. This case has haunted and frustrated Sophie’s family and friends, the investigators and beyond,” said Colonel Barry Wilson, director of the Alaska State Troopers, in a statement. “However, we did it. Investigators never gave up on Sophie.”

State troopers will likely continue to use this technology when DNA evidence is present in their cold cases. “We hope that we can provide this same closure to other families that have long waited for justice,” Wilson said.

Sergie’s case has been a rallying point for those trying to address an epidemic of violence against Indigenous women in Alaska and elsewhere in the Arctic.

The unsolved murder weighed on Alaska Sen. Lisa Murkowski for years; last fall, the senator invoked Sophie’s story when discussing the high rates of violence Indigenous women and girls face across the United States.

“You don’t ever forget these stories,” she said last November, mentioning Sergie’s case and others.

Murkowski spoke in support of Savanna’s Act, legislation to protect Native women and girls in rural and tribal areas. Originally introduced to the Senate by then-Sen. Heidi Heitkamp in 2017, the act is named for Savanna Greywind, a 22-year-old pregnant woman from North Dakota and member of the Spirit Lake Nation who was murdered in 2017.

Savanna’s Act was unanimously passed by the Senate and sent to the House late last year, only to be blocked by Rep. Bob Goodlatte, a Republican from Virginia who retired at the end of his term.

In January, Murkowski, also a Republican, reintroduced the bill to the Senate with Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, a Nevada Democrat.

“In Alaska many rural communities lack public safety and are often hundreds of miles away from the nearest community with a Village Public Safety Officer or State Trooper,” said Murkowski in a statement when she reintroduced the bill. “Compound that with the fact Alaska lacks a unified 911 system, which makes accessing resources even more challenging in many rural communities.”

Savanna’s Act will enable better partnerships between law enforcement at all levels, Murkowski said, and ensure they are working with more accurate data.

“It will also ensure that law enforcement has the resources and cultural understanding to wholly and effectively address this epidemic,” she said. “We have a duty of moral trust toward our nation’s first people and we must all be part of the solution.”

Last week, Murkowski responded on Facebook to the news of a breakthrough in Sergie’s case.

“Sophie’s case reminds us why we need Savanna’s Act—to focus on improving the federal government’s response in cases of missing and murdered indigenous women,” she wrote.

“I commend the efforts of the investigators and law enforcement for opening up this cold-case and showing the community that these horrific acts will not be forgotten. While we can’t reverse what happened to Sophie and erase the pain that her family has endured—my hope is that finally, Sophie’s family may find justice.”

Although Savanna’s Act would strengthen protections for Native women and girls in rural and tribal areas, it doesn’t address the epidemic of violence in urban areas as well — including the city where Sergie was murdered.

Last November, Murkowski and other senators introduced a new report from the Urban Indian Health Institute highlighting the disproportionately high rates of violence against Indigenous women and girls in cities across the United States.

Researchers combed through official and unofficial reports — from police cases to social media — to count at least 506 Indigenous women and girls who were murdered or went missing in 71 American cities since 1943. About 80 percent of the cases in the report occurred after 2000.

Throughout the United States, there were 75 new cases in 2018 alone.

Often, Murkowski said, violence against Indigenous women is seen as a rural problem — especially in places where it’s difficult to maintain or bring in law enforcement forces.

“But now we are learning in a very clear way,” she said, about Indigenous women killed in urban areas.

“As disturbing as all of this is, it’s probably not surprising,” she said. Nearly three-quarters (71 percent) of American Indians and Alaska Natives live in cities — not on reservations or in remote areas.

According to the report, Anchorage has the third-highest number of cases — 31 in all —among the cities surveyed, and the state of Alaska ranks fourth overall in the United States.

“In Alaska, [in] our largest city, we always say that Anchorage is the largest Native village in our state,” Murkowski said.

She summarized Alaska’s high numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls succinctly: “Small population, huge problem.”

More than half of all Native women will suffer sexual violence in their lifetime — a rate that’s 2.5 times higher than women in the rest of the United States.

“Murder is the third-leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women,” the researchers write in the report, and “rates of violence on reservations can be up to ten times higher than the national average.”

Due to challenges in data collection, Sen. Murkowski said, “we have to assume here that the 506 cases probably under-count the incidence of missing and murdered Indigenous girls in urban America.”

In Fairbanks, for instance, police charged a fee to share records, making it too expensive to include most of those cases in this report.

“Most of the cities in Alaska charged us fees that were too high for us to pay,” said Annita Lucchesi, the report’s co-author.

The Anchorage police force was one of the first to provide data, free of charge, and they didn’t question the project, the researchers said. Other cities across Alaska and the U.S. were less enthusiastic.

Abigail Echo-Hawk, one of the study’s authors, said that “Alaska has the opportunity to lead” on finding data and responding to the epidemic of violence.

“We need to be doing more,” Murkowski said, including providing more resources for law enforcement to pursue cases like Sergie’s.