A climate chain reaction: Major Greenland melting could devastate crops in Africa

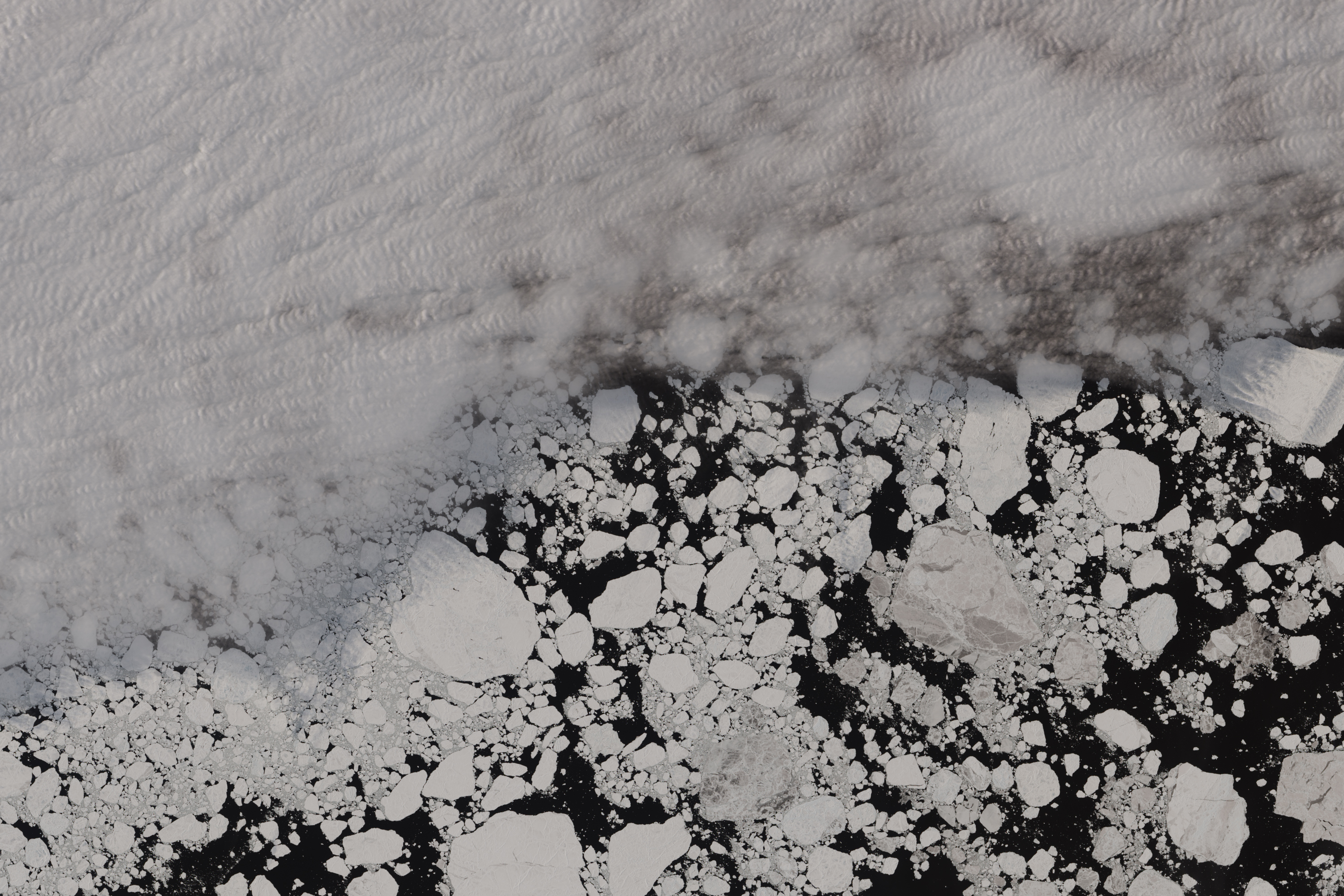

As melting Greenland glaciers continue to pour ice into the Arctic Ocean, we have more than the rising seas to worry about, scientists say. A new study suggests that if it gets large enough, the influx of freshwater from the melting ice sheet could disrupt the flow of a major ocean current system, which in turn could dry out Africa’s Sahel, a narrow region of land stretching from Mauritania in the west to Sudan in the east.

The consequence could be devastating agricultural losses as its climate shifts in the future. And in the most severe possible scenarios, tens of millions of people could be forced to migrate from the area.

“The implications, when expressed in terms of vulnerability of the population in the region are really dramatic, and bring home just how sensitive livelihoods are in this region to climatic change,” said Christopher Taylor, a meteorologist at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology in the United Kingdom and an expert on the West African climate, who was not involved with the new research.

The alarming study, published Monday in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, uses a climate change model to investigate the influence of different amounts of ice loss from Greenland, corresponding to different amounts of global sea-level rise, on the western Sahel’s climate system. Prior studies have suggested that this region may be particularly vulnerable to climatic changes produced by disruptions in the ocean.

The idea is that large volumes of meltwater from Greenland have the potential to slow down a major system of ocean currents known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC. Experts have described it as a kind of giant conveyor belt, which carries warm water from the equator to the Arctic and cooler water back down south. This transport of heat influences atmospheric processes and helps regulate climate and weather throughout the Atlantic region.

As glaciers in Greenland melt, scientists think that the influx of cold, fresh water could disturb this conveyor belt, causing it to slow down. The resulting disruption in the transfer of heat could cause changes in atmospheric patterns throughout the Atlantic and alter weather patterns around the world. In fact, previous modeling studies indicate that ancient periods of ice melt may have caused the West African climate to become drier.

The researchers were interested in finding out whether this might happen again.

To investigate, they assumed a business-as-usual emissions trajectory, which suggests high levels of future global warming and an unclear amount of sea level rise and Greenland melt. The authors modeled scenarios ranging from half a meter to three meters of sea-level rise (1.6 to 9.8 feet), admitting that “the scenario with three meters of sea-level rise is largely above the estimations [predicted] by the glaciologists,” as lead study author Dimitri Defrance, with the Institute Pierre Simon Laplace in France, puts it.

The three-meter possibility was included as an extreme scenario in the study – but climate scientists now think sea-level rise of one or two meters through the end of the century is in the realm of possibility under a high-emissions scenario.

The model suggested that an influx of freshwater from Greenland does, indeed, slow the AMOC, with greater amounts of sea-level rise corresponding to greater effects on the current’s flow throughout the century. And this slowdown has major consequences for western Africa. Under a meter or more of sea-level rise, the result is an immediate and significant decrease in precipitation in the western Sahel, with up to a 30 percent reduction in rainfall between the years 2030 and 2060. At the same time, temperatures in the region are expected to rise as a result of the continued progression of climate change.

These combined changes have potentially grave consequences for agriculture, the researchers suggest. As temperatures rise, many crops will require more and more water to survive, and a reduction in precipitation could be devastating.

The researchers focus on millet and sorghum, two of the region’s staple crops, as examples, projecting that the area of land fit for cultivation in the Sahel could shrink by more than 400,000 square miles throughout the century under a meter or more of sea-level rise. Tens or even hundreds of millions of people, depending on future population changes in the region, could be affected by the agricultural losses, with many potentially forced to migrate to other areas to survive.

“The solution is migration or adaptation,” Defrance said. It’s possible that other less water-intensive crops could help make up for some of the losses, he suggested, but it’s likely that many people would be forced to relocate under these conditions.

Because the study relies on a business-as-usual trajectory, its conclusions are not a definite portrait of the future. Many scientists think that the terms of the Paris climate agreement, in which nations around the world have agreed to curb their greenhouse gas emissions, have set us up for a less severe climate future than the business-as-usual scenario predicts – although the recently announced U.S. withdrawal from the agreement may make its future success less certain.

It’s difficult to say how the study’s results might differ under a slightly less severe warming trajectory, said Thomas Haine, an expert in ocean circulation at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved with the new research. The climate consequences for western Africa could also be less severe, or they might end up being similar. Additional modeling would be required to find out.

Both Haine and ocean physics expert Stefan Rahmstorf of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research also caution that the new study only relies on simulations from a single climate model. To add certainty to the study’s conclusions, they point out, the same simulations should be run with different climate models in the future. As such, Haine suggested that the research conclusions constitute “an interesting provisional result.”

But the general results are credible, according to Rahmstorf, who was also not involved with the research.

“It is well-established by now from past meltwater events in Earth’s history that such events have had major impacts on tropical precipitation, and the physical mechanisms for that are basically understood,” he told The Washington Post by email. “Thus, even without model simulations we would expect important tropical rainfall changes in case of a major slowdown of the Gulf Stream System, because that would change temperature patterns in a major way.”

And, Defrance added, while the new study focuses specifically on the western Sahel, it’s by no means the only place that could be affected. While the impact on agriculture in other places may be less severe, the AMOC influences climate and weather throughout the Atlantic, including Western Europe and the east coast of North America.

“The climate change induced by the ice sheet melting is around the world,” Defrance said.