A new history of the North Pole uncovers its deep significance for modern civilization

The new book ”North Pole: Nature and Culture,” by Cambridge geographer Michael Bravo reminds us that the pole has a long, tangled cultural history.

What exactly is the North Pole? How are we to understand the North Pole’s significance to the world today? has all the mysticism and wonders which so enthralled the early explorers and their eager audiences now completely vanished, reduced to bland insignificance by icebreakers, flags, submarines, tourists and jets in thoughtless shuttle across the polar sky?

Or do we owe the North Pole our respect and recognition, perhaps even our protection, for its part in the build-up of our civilization and intellectual wealth, so urgently needed in an age of climate change and other challenges? Does the North Pole belong to our common cultural heritage as a phenomena we must cherish, even as more entrepreneurial agents zoom in on the pole’s potential for fish, oil, gas and minerals (potential which is, by the way, still undocumented)?

Three nations, Russia, Canada and Denmark — with Greenland — all argue that the rights to the ressources at the North Pole and the seabed surrounding it belong to them. All three have invested substantial time, effort and finances in their quests to provide proof of ownership. Never before has any nation come this close to claiming ownership to the North Pole. Icebreakers, planes, submarines and scores of scientists have been mobilized, but throughout these campaigns the key question of how to understand the cultural, intellectual and historical value of the North Pole has been notably absent.

I know for sure that in Denmark, my own country, nobody at government level has so far aired any thinking on the subject, and I am still to learn of any such contemplation within official circles in Moscow and Ottawa. Should any reader know of such, I would be pleased to receive notice.

The beginning of time

Luckily, those interested in the intricate issues of the intellectual and historical value of the North Pole now have easy access to passionate and expert assistance. In a lucid new analysis of how the North Pole have inspired natural scientists, philosophers, cartographers and others from ancient Greece to our days, Michael Bravo, who is a scholar of the history of science and head of Circumpolar History and Public Policy Research at the Scott Polar Research Institute at University of Cambridge, lights a thrilling path in the dark.

In his recent book ”North Pole: Nature and Culture,” he deftly extinguishes any remaining doubts about the North Pole’s current cultural, historic and phenomenological significance:

“I offer the reader a way to understand why the North Pole truly matters to anyone who knows that our home, planet Earth, is a globe,” he writes. The North Pole, he finds, “has refracted our understanding of the planet on which we live and the quest to master or knowledge of who we are.”

“Spatially, when standing at the North Pole, every direction faces south. Temporally, the North Pole is timeless and has to this day no allocated longitude or time zone. This is no coincidence: The North Pole can be thought of as the origin of time because all lines of longitude, which define time zones, pass through North Pole. Emperors and philosophers through the centuries have recognized the North Pole’s special significance as a point that defines global time, but is not itself subject to it,” Bravo writes and as I talk to him on the phone from Cambridge, he continues:

“Every frontier is a moving boundary, that has two sides. So if economic national expansion is pushing on the northern frontier, what is it pushing against? That is a question for the present day, because the question of what pushes back against expansion, is also a question about the conditions on which we inhabit the Earth today,” he says.

“The North Pole and the Arctic is the temporal and spatial framework in which we understand our economic, geographical, cultural place in the world,” he says. ”So as nation states negotiate new national boundaries and rights to access resources, the North Pole reminds us that we live on a planet with limits. If we talk about going beyond the pole, it becomes a paradox, because you cannot go further than the North Pole. The idea of travelling ’beyond the Pole’ implies a space where the world is transformed. It leads us to understand our human limits in rather different terms. The North Pole shows us the limits of the world we inhabit, but it also challenges us to ask how is it that the world is made whole? How is this an inhabitable world? The North Pole, this placeless place, has been and remains integral to our understanding of our human condition and the way we are bounded to the surface of this planet,” he says.

At the heart of cosmos

In his book, Bravo explains how “for Greek and Arab astronomers, poles were at the heart of the architecture of the entire cosmos.”

I wish I had known earlier. In 2012, I learned of an entirely different approach. I was at the North Pole covering the Danish-Greenlandic attempts to secure proof that the Arctic seabed is irrefutably connected to the bedrock of Greenland and that the rights to the resources on the bottom should therefore belong to Greenland and indirectly to Denmark, which still holds sovereignty over Greenland. Travelling for weeks on an icebreaker, I was told that the North Pole has essentially of no value or significance in our time and age. It is, I learned at that time, basically an irrelevant spot in a bucket of water.

I know now from Michael Bravo’s book that the learned and wise in ancient Persia, Egypt, India and Greece were all deeply preoccupied with understanding the North Pole. Or, more precisely, they were first and foremost preoccupied with the North Pole’s even more revered celestial sister, which they imagined as a fixed entity close to the pole star on the inner surface of the shell that encapsulated the universe. Our earth was the eternal and entirely still center of the universe; solidly positioned on the axis that ran from the celestial North Pole down through the North Pole of our planet.

“Any astrologer worth his salt was on the lookout for divine conjunctions of constellations and stars, and omens or portents of dangers ahead. Hence the importance of the geographical North Pole came about first because of the celestial North Pole and its pole star, and our knowledge of the Earth’s grid of latitude and longitude was a projection derived from mapping the celestial realm,“ Bravo writes.

A new view of the world

In the 15th and 16th centuries the North Pole again took on a lead role in the evolution of a new view of the world and in the development of our ability to navigate the globe.

“Without poles there could be no geography and crucially, no system of orientation for navigation,” Bravo writes.

The creation of new ways to understand the architecture of the globe spun around the North Pole, and facilitated new empires, colonization, trade routes and other features of early globalization.

“Thus the North Pole provided one of the main keys to help unlock the basic question of human orientation — to know where we are at any moment in time and to know on what course we are heading,” Bravo writes.

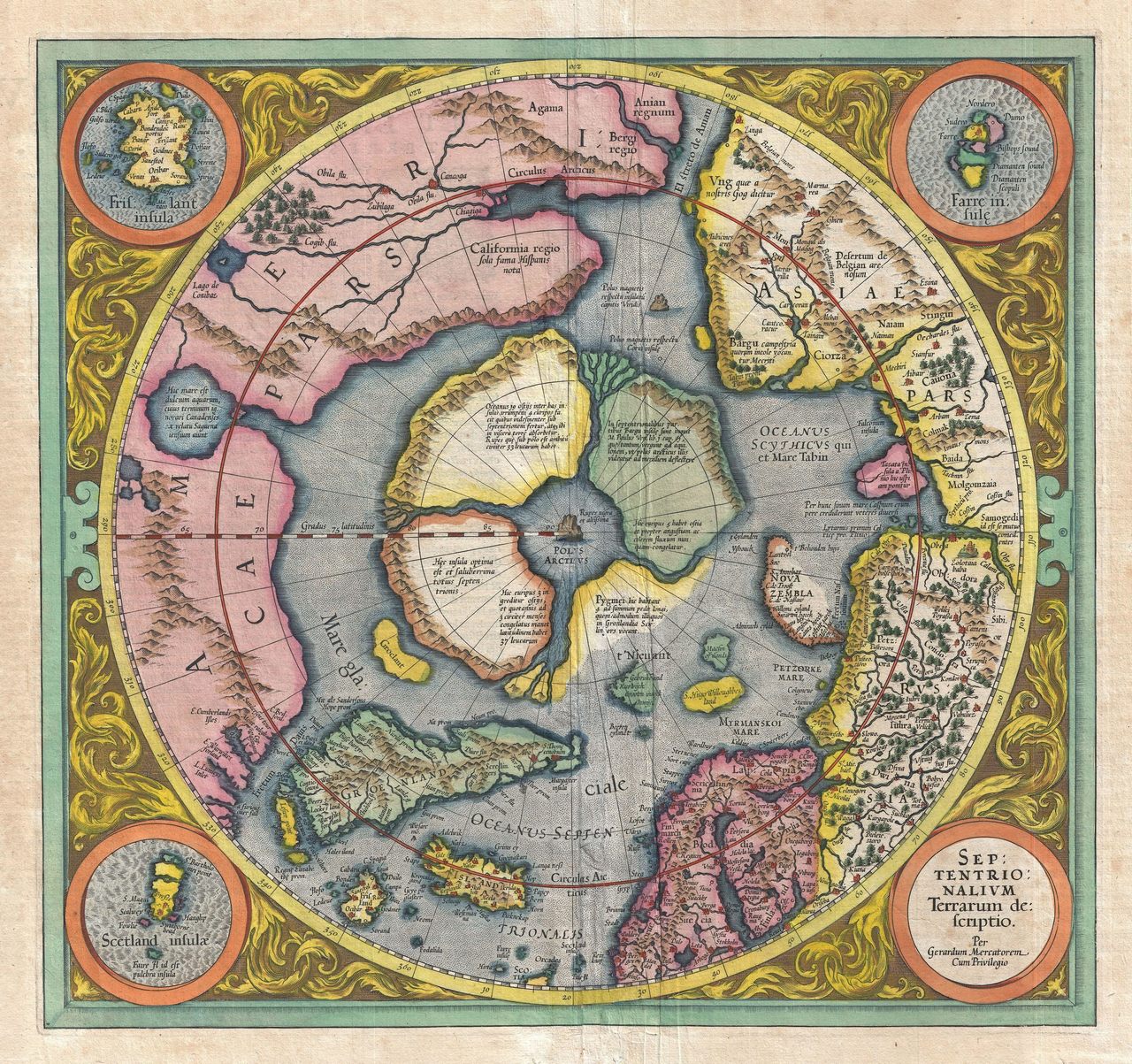

Renaissance artisans, mathematicians, cosmographers and cartographers, in Vienna and Venice not the least, created beautiful immaculate globes and maps on which the North Pole shone as the center of new illuminations of our divine connections. Suddenly Europeans were learning to see the world in an entirely new light. They were taught how to see themselves and the planet they inhabited from above; a completely new perspective, which was particularly helpful in an age where many struggled to comprehend the astonishing voyages of the likes of Christopher Columbus, Vasco da Gama and Ferdinand Magellan.

“These special polar maps conferred beauty and prestige on atlases in a unique way. These projections acquired an aesthetic significance and prominence that became synonymous with a new way of viewing the world, as though gazing down on the world from the celestial pole,” Bravo writes. In this way and with the North Pole very much in the center of things, cartographers like Peter Apian (1495-1552) and his successors helped much of Europe to an intellectual leap, long before any European had been anywhere close to the North Pole.

”For philosophers of the enlightenment like Kant, the human condition was one of being anchored to the Earth, like ants unable to escape the limitations of a field of vision placed very close to its surface,” Bravo writes. Cosmographers like Apian and his successors made the globe and its positioning in the universe easier to fathom and rulers and emperors like the Habsburgs in Austria and others with imperial visions readily adopted these tools for visualization of their ambitions. The North Pole’s significance grew and grew along a wide spectrum of sciences and the arts.

“It is the story about a wider circle of Europeans, mathematicians, cartographers, cosmographers not far removed from the contemporary circle of Renaissance artists and architects like Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo da Vinci. The idea of looking on Earth from above is intimately connected to the story of the invention of linear perspective, which is much better known and celebrated in the world of art history of course,” Bravo tells me.

Paradise at the North Pole

In the 18th and 19th centuries much of the world followed with growing excitement how seafarers and explorers of many kinds travelled, at great peril, closer to the North Pole by ship, sledge, foot or balloon. Michael Bravo describes in detail how the narration of these endeavours, many of which did not achieve what they set out to do, became still more elaborate, and also how the idea that the North Pole was intimately connected to its celestial sister in Heaven continued to inspire more fantastic interpretations for a long time, including the one that Paradise was originally located at the North Pole.

“Safe from prying eyes, the Earth’s polar axis and poles possessed a strong appeal as places for locating narratives and symbols of absolute sacredness and purity,” Bravo writes. Even the colossal amounts of ice at the pole could be explained. With the fall of Eden, of course, man had called the freeze upon himself. The Boston University’s first president, William Warren (1833-1929), an esteemed professor of comparative religion, collected evidence from the new field of anthropology, from linguistics, archeology and from his own research into religious thought in Iran, China, Japan and elsewhere. He described in conclusion an antediluvian continent in the north with an unusually tall mountain centered at the North Pole. This he designated as the original site of Paradise and the very cradle of the human race.

In “Paradise Found” (1885) Warren explained how this antediluvian continent was first submerged by the biblical deluge and then by an ice sheet animated by an abrupt shift in the Earth’s polar axis and subsequent cooling. In Warren’s telling, refugees from these calamities fled south and soon established the first communities of white Aryans.

Today, Warren’s views would be subject to criticism because of his commitment to defending creationism against evolutionary theory. And even in his own time, his use of racial theory to explain historical migrations was controversial and widely contested. Michael Bravo, however, describes how North Pole variants of the history of Paradise penetrated far into a number of ethnonationalist movements in many countries, including strands of Hinduism in which a large Mount Meru at the North Pole plays a significant mythical role.

Powerful agents in Nazi Germany, such as Adolf Hitler’s close associate Rudolf Hess, also made use of North Pole Aryan mysticism in their Thule Gesellschaft, a influential private society that forged key elements of Nazi thinking.

“For National Socialism, the polar origins served as a repudiation of the traditional orientation of geography towards the sacred sites of the Judaic Mediterranean,” Bravo writes.

An American North Pole

He also uncovers how the polar projection of the North Pole emerged after World War II as though it were a surprising new projection:

“American writers in the 1940s began to write about polar projections and the view over the North Pole as though it were a new idea, adopting it to illustrate a new post-war vision of the world as a smaller connected global village. America’s rethinking of its position in relationship to the whole globe made the North Pole important once again. Making the pole a symbol of American and Soviet foreign policy meant writing out its longer and more complex historical narratives,” he says.

Today, a few decades later, we talk more often about the North Pole as an object in the quests by Russia, Canada and Denmark/Greenland. The submissions by the three nations for the rights to the resources on the seabed of the Arctic Ocean are dealt with by the Commission on the Continental Shelf of the UN, and most observers expect the issue to be resolved peacefully within a decade or two, perhaps finally through direct negotiations between the three governments, since the commission is not mandated to solve the problem, if two or more nations have overlapping, valid claims.

In this elaborate diplomatic process, however, the more difficult question of the cultural value of the North Pole is not dealt with at all. The UN’s expert commission will not ask whether the dispute over potentially recognizing rights to the North Pole seabed as belonging to a single nation’s jurisdiction will somehow damage a phenomenon that is presently valuable to the whole of humanity. Will a precious gem of world heritage lose its thrill and value through this type of handling? Will whatever magic and substance that still remains be lost for future generations? Or is the cultural and historic value of the North Pole, now so thoroughly documented by Michael Bravo, perhaps immune to all we do today?

Wisely, Michael Bravo hardly comments on the current efforts or ambitions of the three states involved, and neither does he make suggestions as to whether a protective zone around the North Pole or the like would be desirable. His is the scholarly contribution, a rich and detailed account of the history and intellectual discovery of the pole, and we must then make up our own minds where this should all lead.

A view from Greenland

In the Danish Kingdom, only one key decisionmaker has ever made cohesive comment on the cultural value of the North Pole, namely the former Prime Minister of Greenland, Kuupik Kleist.

Not that the North Pole traditionally played any particular role in Greenland. Way back, the people of the very north of Greenland named the North Pole Qalasersuaq, the great navel. It lay far from the lands of humans, where only shamans could travel, and it was not a nice place, but rather a dangerous deep with no hunting to speak of. Since then, Qalasersuaq became a neutral, almost bland designation for the very point at 90 degrees North. As Michael Bravo explains in his book, the pole star was also never very significant as a means of navigation in the Arctic. This far north, the pole star shines too high in the sky to be very useful for laying a course.

Even so, Kuupik Kleist took a stand in Nuuk back in 2007: ”I believe that it is in the interest of Greenland that the North Pole and adjacent areas should not be given to any single state, but remain an area of common responsibility,” he wrote.

In 2010, after taking office as Prime Minister in Greenland’s Self Rule government, his views became known in Copenhagen when I interviewed him for a book, and it was not much appreciated by the Danish government. Nervousness arose that the delicate talks with Canada and Russia about the Arctic seabed might be disturbed, and within a day Kuupik Kleist explained to the public that his view was “private” and not that of Greenland’s government.

In May this year, however, he explained to me that he is still of the firm conviction that the North Pole and some section of its surrounding waters ought to be somehow protected for its cultural significance. “The North Pole is something special,” he said. But now he is no longer in politics and his view seems to have found no other real friends.

Martin Breum is a Danish journalist and author, based in Copenhagen. In 2012 he covered the Danish-Greenlandish LOMROG III expedition to the Arctic Ocean and North Pole. He writes regularly on Arctic affairs for ArcticToday.com. Find him at www.martinbreum.dk.