A new oil well is too close to Norway’s Lofoten Islands for environmentalists’ comfort

No drilling is allowed in the waters nearest Lofoten, but a new well was begun earlier this month near the edge of the excluded area.

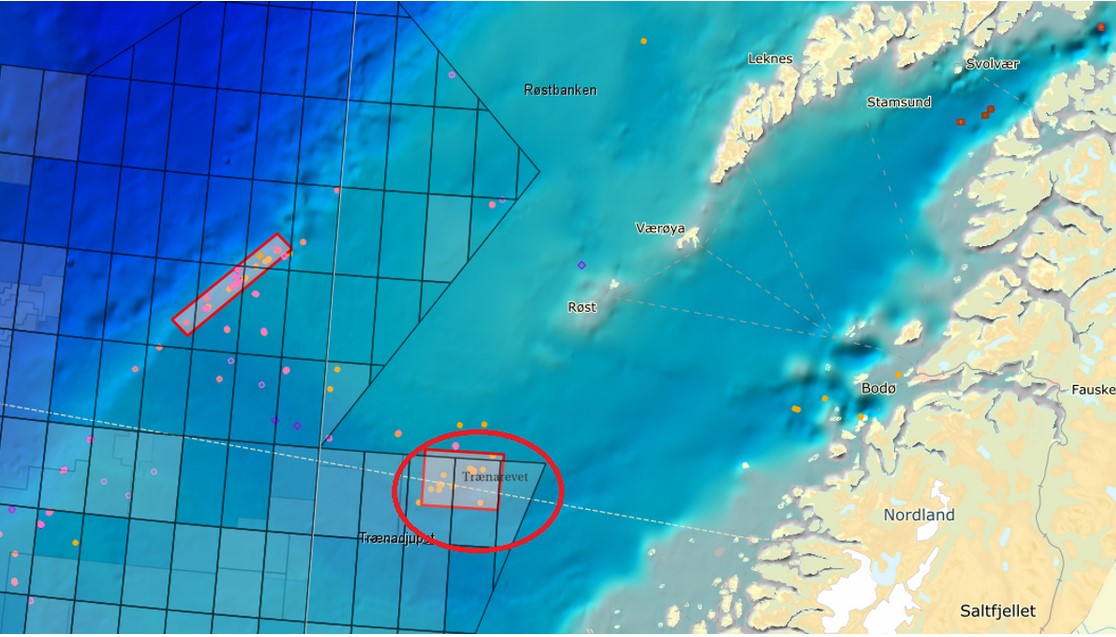

The closest thing to drilling in the oil-rich waters around the Lofoten Islands these days is licence block 896 of the exploration area known as Nordland V. Oil exploration is currently not permitted in Lofoten, and, depending on your view, block 896, which is located adjacent to the archipelago, is either dangerously close to spoiling its fishing and tourism industries, or tantalisingly close to tapping into the 1.3 billion barrels of oil its waters are estimated to contain.

Despite protests from Bellona, a Norwegian environment group, Wintershall Dea, which won the license in 2017, began drilling in block 896 at the beginning of November and is expected to finish by the end of the year.

Norwegian officials are aware that not everyone is comfortable with the location and they have sought to allay what fears they can by requiring Wintershall Dea live up to stricter guidelines than operations elsewhere, including by forcing the company to halt operations in the spring, when fish and birds are breeding. The extra requirements reportedly add as much as 20 million kroner ($2 million) to the price of an operation expected to cost 300 million kroner.

Should Wintershall Dea find as much oil as it expects, those extra costs will be worth it: the company’s estimates suggest that block 896 contains, between 500 million and 1 billion barrels of oil. Although it projects the chances of drilling a commercially viable well are only 30 percent, that figure is twice the industry average.

Likewise, Wintershall Dea’s studies of currents in the area suggest that any oil released during drilling would, in most instances, be carried away from Lofoten. In the event that a spill did travel towards the archipelago, the company calculates it would likely take six days for the oil to reach land — during which time crews could work to disperse the oil while authorities took measures to prevent it from reaching land.

Such explanations have done little to ease the concerns of environmental groups. Chemical dispersants, they admit, do help break up a spill, but they cause it to sink and would likely do harm to coral reefs.

[Oil drilling in part of Norway’s Arctic just became a lot less likely]

Another concern is the effect a spill would have on fish. Biologists with Norway’s Institute of Marine Research (HI), suggest that even though fisheries would start recovering five years after spill, they would could be affected for as long as 50 years, not the 10-15 years suggested by previous studies.

In a paper, published in the March 29 edition of Frontiers in Marine Science, HI scientists concluded that such long-term changes would likely be seen even if only 10 percent of fish were to die in an spill — though they also looked at what would happen in scenarios where 50 and 90 percent of fish were to be killed. The resulting changes, they found, would have significant impacts on individual species, fisheries in general and surrounding communities.

“The fact that an incident like this can have such long-term, negative impacts on an ecosystem shows the importance of the precautionary principle,” said Erik Olsen, HI’s head of research.