A new tusk analysis reveals the life-cycle of an ancient Alaska woolly mammoth

University of Alaska Fairbanks researchers were able to use the tusk to recreate key moments in the life of "Kik," who roamed Alaska's Arctic some 17,000 years ago.

ANCHORAGE — A woolly mammoth that roamed Alaska 17,000 years ago covered enough ground in its 28-year lifetime to nearly circle the globe twice, an analysis of one of its tusks suggests.

The findings, detailed in a study published Thursday in the journal Science, show how the male mammoth went through infancy and youth as part of a herd, but died alone from starvation in Alaska’s northernmost mountains.

“This really is one of the very first insights into the life history of an Arctic woolly mammoth,” said Matthew Wooller of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, co-lead author of the study of the now-extinct ancestor of the modern elephant.

The mammoth’s movements were traced through analysis of isotopes in one of its well-preserved tusks.

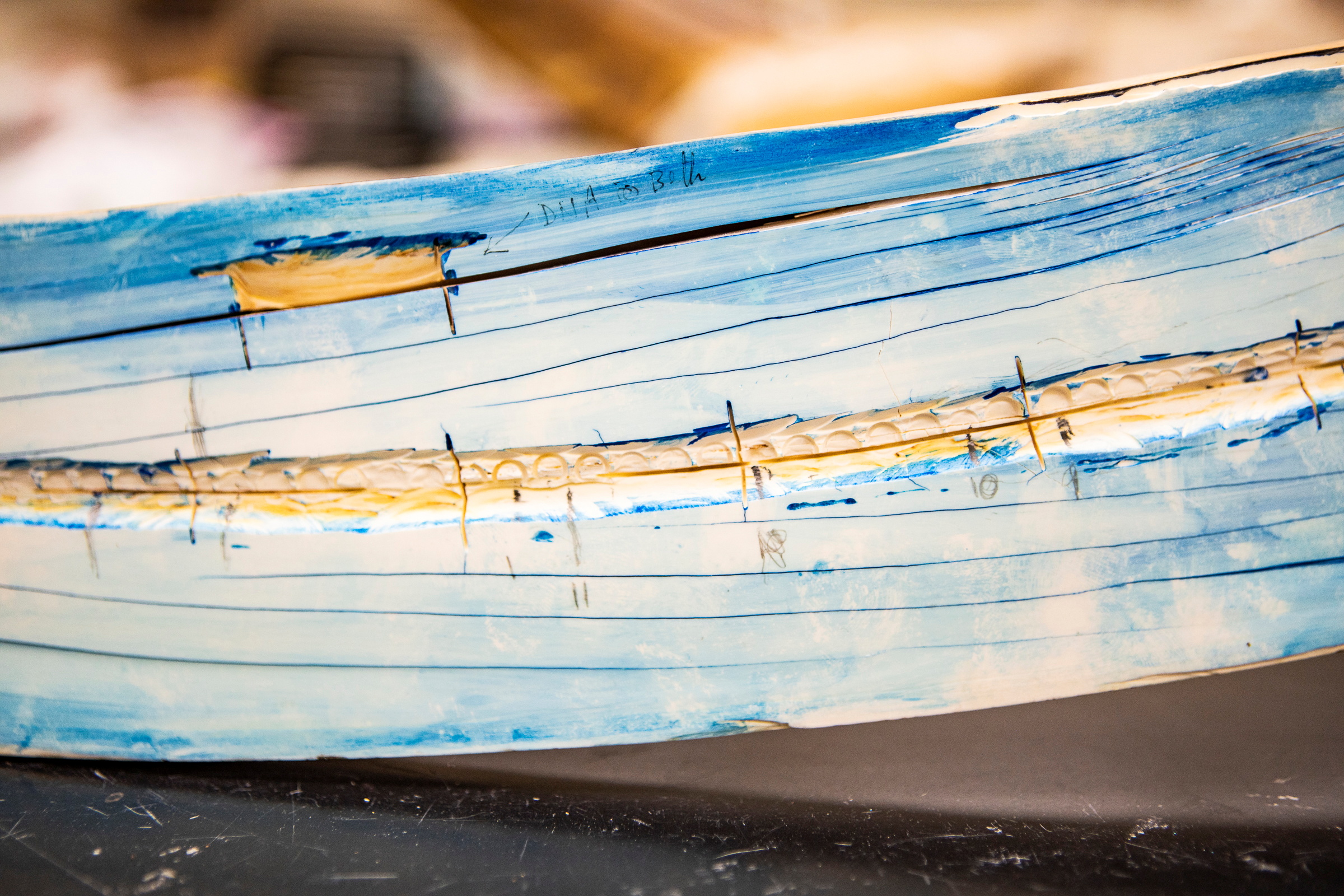

To generate more than 400,000 data points for the study, the scientists sliced open the tusk, exposing the layers that were added as the animal grew. Those layers, Wooller said, are like “sugar ice cream cones stacked one inside of each other.”

In its early years, the mammoth — named Kik by researchers after the river where its remains were found — moved around the area that is now the Lower Yukon River region, Wooller said.

Though glaciers extended far south at the time, much of Alaska, including that region, was glacier-free. Alaska areas that are now boreal forest were grassy steppe-like terrain, ideal for grazers such as woolly mammoths, he said.

“It was probably hanging out with the herd, with its mother and other members of the herd,” Wooller said.

At age 15 or 16, the mammoth dramatically increased the distance and range of its travels, heading periodically to points much farther north and higher in elevation.

It’s likely that the mammoth left the herd then, Wooller said. Its behavior mirrored patterns in some modern elephant herds, in which maturing males are “encouraged — and I would put inverted commas around that word,” to strike off on their own, he said.

In its later years, the mammoth roamed some routes that caribou use today, Wooller said. It is possible that the mammoth, as it traveled seasonally to find food, shared migration paths with ancient caribou, he said.

Its demise likely came at the Arctic gravel bar where its remains were found in 2010. The combination of two tusks and a partial skull there “gives us pretty good confidence that that’s where it died,” Wooller said.

At the end, it endured nutritional stress, the tusk analysis showed. “It looks like in its last year of life it slowed down to not much moving around,” Wooller said. “We have kind of a smoking gun of what killed it.”

The study does more than just satisfy curiosity about extinct Ice Age creatures. It is relevant to species living in today’s rapidly changing Arctic, Wooller said.

“Our work helps shed a light on environmental concerns we have about modern animals like polar bears and caribou that live in the Arctic today,” he said.