A Quebec couple sparked outrage by fleeing to a remote Yukon village to escape COVID-19

Remote communities such as Old Crow are especially vulnerable to pandemics like the coronavirus outbreak.

The young couple sold their possessions, picked a spot on the map, and started driving across Canada.

They traveled 3,400 miles from their home in Quebec to Whitehorse, Yukon, and then boarded a 500-mile flight to Old Crow, a Vuntut Gwitchin community of about 250 people, north of the Arctic Circle and not connected to the North American road system.

The couple, about 35 years old, had no food, no cold-weather gear, no lodgings booked — and, the community hopes, no virus hidden in their bodies.

On Friday, when the two landed in Old Crow, they were met by Paul Josie, the community’s emergencies officer, who was handing out pamphlets about COVID-19 at the airport. He didn’t recognize them, and immediately ushered them into isolation in the only hotel in town — a few rooms above the local cooperative store — until they could fly back out on Sunday.

“They thought they could come to Old Crow and find a job and find a place to live,” Josie told Vice.

But remote communities in the Arctic are especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

In neighboring Alaska, such communities have also imposed strict travel restrictions due to the vulnerable populations and limited medical capabilities in Alaska Native villages. Elsewhere in the Arctic, Greenland banned travelers from leaving the capital Nuuk for more remote communities, while several hamlets in Nunavut acted to limit visitors even before the territory did so.

Yukon declared a public health emergency, along with Northwest Territories and Nunavut, on March 19. Yukon imposed non-essential travel restrictions in and out of the territory on March 22.

In a media briefing on Monday, Dr. Brendan Hanley, Yukon’s chief medical health officer, said that the couple exposed a loophole in Yukon’s travel restrictions. Travelers from outside the territory are required to self-isolate for 14 days after reaching their destination. But there was no requirement that the couple do so before arriving in Old Crow.

“They did not contravene an order and therefore will not and could not be charged,” Hanley said. “The order as it stands is for visitors or travelers to Yukon to self-isolate, but it also allows for people to reach a safe place of self-isolation.”

“Of course, it was not intended in this case to be Old Crow, and Old Crow took appropriate measures as a chief and council and community,” Hanley said.

Going forward, he said, airlines will have scripts to read during check-in about restricted travel in remote areas, and flights will be met by greeters like Josie to make sure no one from outside the community arrives. Old Crow, which is a fly-in community, also requires written permission to enter the community.

“I really commend the levelness and the thought that went into the measures that Old Crow is taking,” Hanley said. “It is certainly a particular community in Yukon at risk because of their isolation from road access.”

Though the couple was “misguided,” Hanley said, “to me this is a very human story.”

“It’s a story of two people who were afraid, who wanted to seek refuge, and who thought they were going to a safe place,” he said.

“And although there were already measures in place to guide to guide their behavior, clearly, some of those measures could be stepped up and those measures are being stepped up.”

Although he declined to say where the couple is now, they are safely in self-isolation, he said.

While Old Crow does not have any confirmed cases of COVID-19, Quebec had 3,430 cases and 25 deaths from the coronavirus by Monday. Yukon announced its fifth case on Monday — four of which have been linked to the same cluster of cases.

Communities such as Old Crow are particularly vulnerable to the coronavirus for several reasons. Other respiratory illnesses are common, while medical services are extremely limited. About one-fifth of the residents are elders.

Old Crow already has a housing shortage, and the pandemic has delayed construction of new residences. But close living quarters can allow the virus spread more easily.

“We do not have the capacity to deal with a very robust outbreak of the COVID-19,” Dana Tizya-Tramm, chief of the Vuntut Gwitchin, told Politico. “Our community, albeit remote, is not a life raft for the rest of the world.”

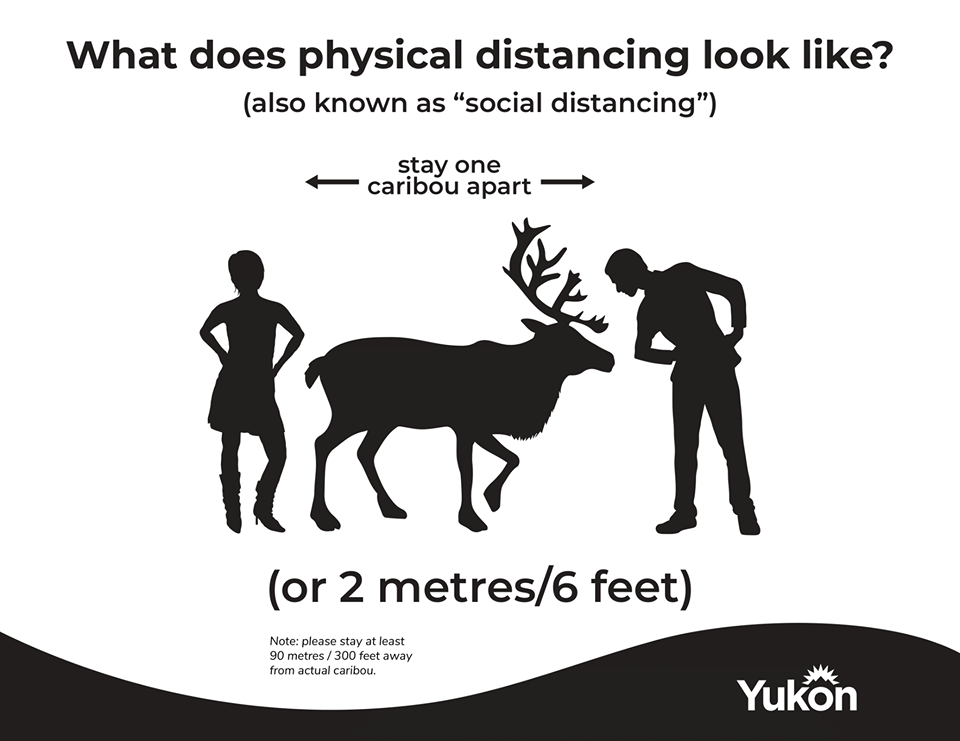

Hanley stressed Yukon’s long-term planning to address the coronavirus pandemic. Restrictions like physical distancing and travel limitations may be in place for months to come, he said.

“Let’s not underestimate how brutal a war this could be if we let down our defenses,” Hanley said.

“Protecting the North is Canada’s duty and our responsibility. When COVID tries to make its way in, we must not only flatten that curve. We need to beat it to the ground.”