A simmering Aleutian volcano could provide the breakthrough geothermal energy project Alaska has been waiting for

Large-scale geothermal energy hasn't worked out yet in Alaska. Makushin Volcano, near Unalaska/Dutch Harbor could change that.

Arctic renewable energy has the potential for a global impact, but stories of energy transformation in the region are often overshadowed. For the month of September, ArcticToday is launching a special focus on renewable energy in the Arctic and this piece is part of that coverage. Find the full series here, or subscribe to our daily newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter to be the first to read new installments.

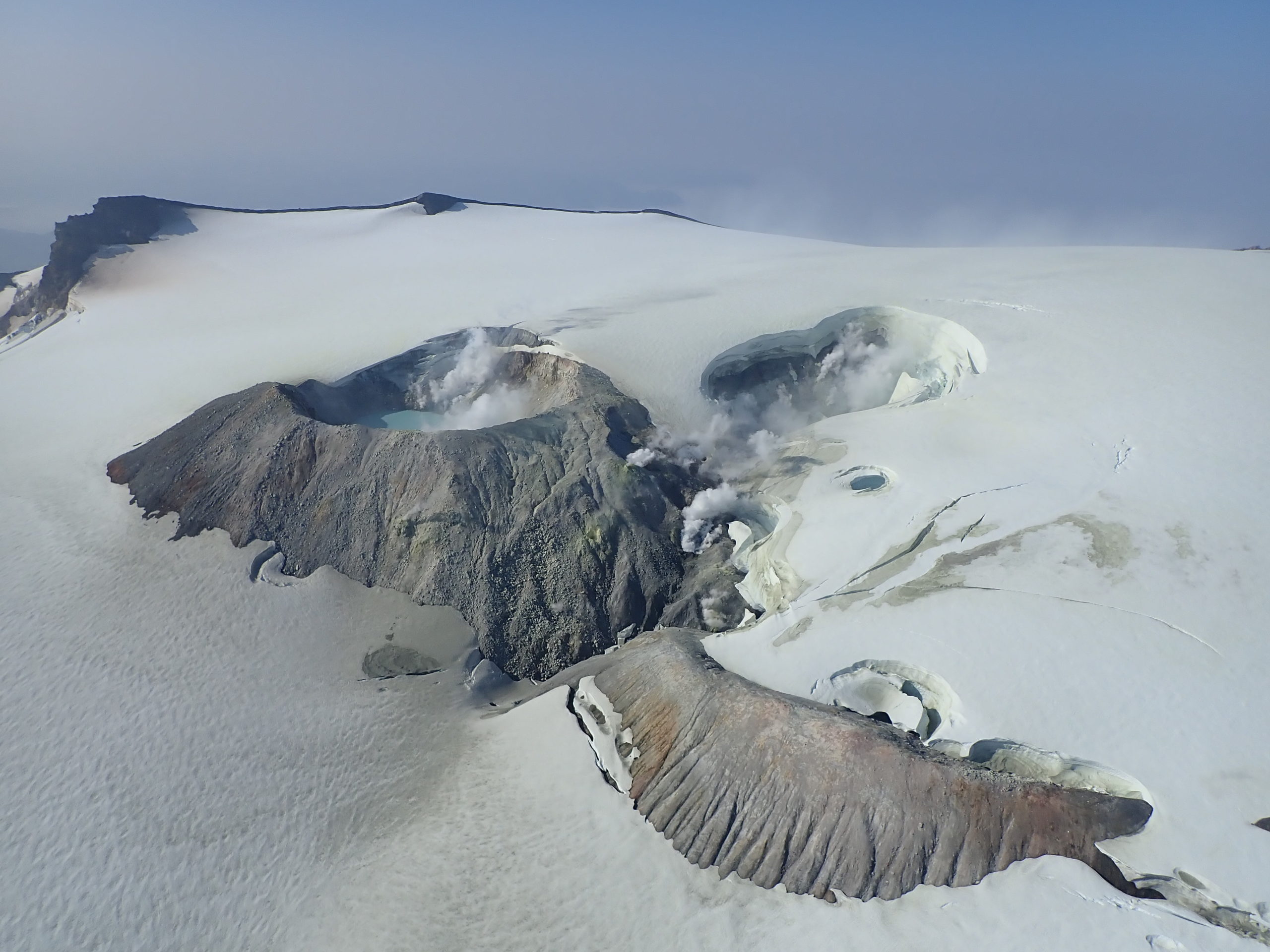

Makushin Volcano, which rises to 5,906 feet and looms over Unalaska/Dutch Harbor, the nation’s top-volume commercial fishing port, has long inspired awe and imagination.

An Aleut legend about the frequently steaming mountain on the northwest corner of Unalaska Island tells of some ill will between it and a volcano on Umnak island to the southwest. Long after the battle between them, the volcano continued to be simmer in anger, but the neighboring volcano, now known as Recheshnoi, settled into meek quietude, according to the legend.

Gavril Sarichef, a Russian navigator who mapped Unalaska and many other Aleutian islands at the end of the 18th century, was also impressed with Makushin, calling it “Ognedyshushchaya Gora,” meaning “burning mountain”

The travel publication Fodor’s Travel recently put Makushin as ninth on a list of the 10 most dangerous U.S. volcanoes. It last erupted in 1995, but a swarm of earthquakes that started in mid-June shook Unalaska and prompted scientists to issue an advisory about a possible eruption to come.

Now, renewable energy enthusiasts hope, Makushin will shake up Alaska in a different way.

A new partnership is seeking to use heat from the volcano to power Unalaska/Dutch Harbor, including the giant plants that process some of the nation’s biggest seafood harvests — freeing the Aleutian port from its reliance on imported diesel fuel that is burned in a powerhouse that dates back to World War II.

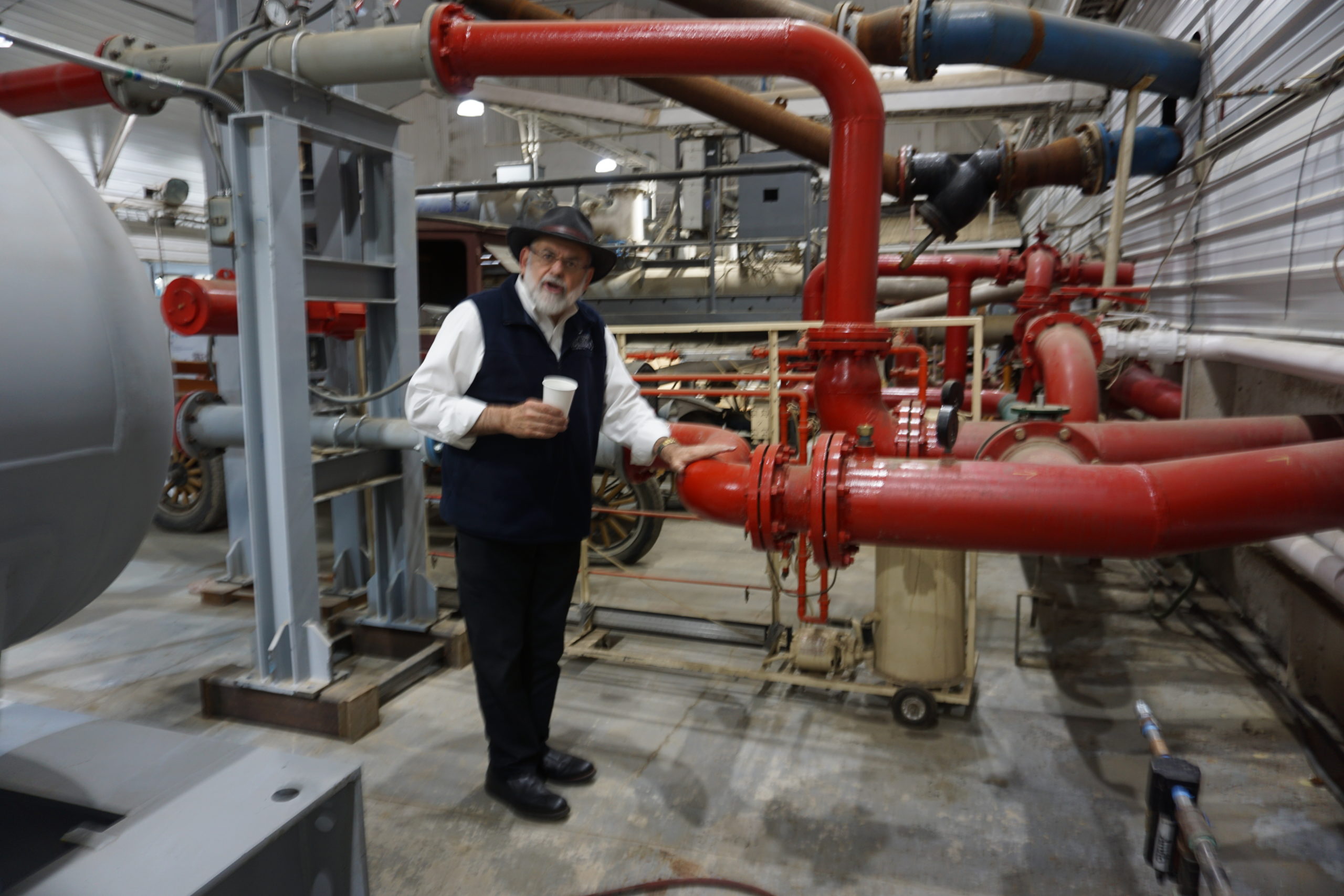

“They’ll be the first community, I believe, with zero smokestacks anywhere,” said Bernie Karl, longtime proprietor of Chena Hot Springs near Fairbanks and Alaska’s best-known geothermal-energy success story.

The Makushin partnership pairs Chena Power LLC, an offshoot of Chena Hot Springs, with the Ounalashka Corp., the local Alaska Native corporation formed under the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

Chena Hot Springs has been able to power its entire operation, including year-round refrigeration of an ice hotel, with energy from the hot springs that flow into the resort’s pools. Makushin promises to be a much more significant accomplishment, Karl said. “Chena Hot Springs will take a back seat to this,” he said.

The plan is for the Ounalashka Corp.-Chena Power partnership to build a plant at the base of the volcano to convert its heat into power and transmit that to the town about 15 miles to the east, where it would be used by Unalaska’s approximately 4,500 year-round residents, its massive seafood plants and its several thousand visiting fishery and maritime workers.

Makushin has been long identified as one of Alaska’s most promising sources of geothermal energy. Proposals for using the volcano to supply power to Unalaska go back decades. In 1984, for example, there was a hard look at the concept of a hybrid geothermal-diesel system. Another proposal fizzled out in 2015 for lack of funding.

This time around, things are different, proponents say.

Unlike in the past, Karl said, there is an alignment of sponsors with strong incentives to make it work. A critical element is the involvement of Ounalashka Corp. as a partner, he said. Ounalashka now owns title to the land where the power plant and associated facilities would be built, which Karl describes as a legal formality that recognizes cultural reality. “It’s been the native people’s land over the last 10,000 years,” he said. The practical effect is that Ounalashka’s land ownership streamlines the process of planning and building the project, he said.

With the city’s official blessing, the partnership could secure a loan of up to $500 million from the U.S. Department of Energy.

Karl has some ambitious ideas that go beyond supplying energy to Unalaska’s homes, businesses and huge seafood plants. The volcano’s heat would be channeled through a 30-megawatt plant for use in greenhouses sprawled over 40 acres that will grow vegetables and fruit to feed Unalaska — and beyond.

“It’ll take care of food security for the entire state,” he said. The port already supplies more fish than any other in the nation, he noted. “How about if you had all the food to go along with the fish?” he said.

Karl has experience in that area; at Chena Hot Springs, he combined his passion for gardening with his passion for geothermal energy and has overseen what amounts to a mini-farm that produces food and flowers for use at the resort and for sale in the greater Fairbanks area.

Perched directly on the seismically restless and frequently erupting Pacific Ring of Fire, Unalaska might seem natural for geothermal energy. And Unalaskans, political leaders and city residents, have expressed a lot of support for the Makushin geothermal project.

But economics remain challenging. Among the biggest hurdles is the need for a 30-year commitment from the city, a tough financial call for local officials to make.

After a period of study and back-and-forth negotiation, the city decided to take that leap of faith. On Aug. 31, it signed a 30-year power-purchase agreement with Ounalashka-Chea Power.

The signing had been approved by the Unalaska City Council. Council members on Aug. 25 voted for a resolution endorsing the agreement, concluding that the risks were worth taking.

“Sometimes you have to take risks and sometimes you have to go out on a limb because that’s where the fruit is,” said council member Shari Coleman.

Potential rewards include enhanced attractiveness for the seafood industry — which could market its fish in the future as being powered by “green energy” — and economic diversification, council members said.

The modern Makushin plan is more advanced than those considered in the past, but there is only a narrow pathway to making it economic, consultant Mike Hubbard has advised the city.

Along with the right size — in the range of 30 megawatts — the project needs the right mix of peak load and customer base to pencil out, Hubbard said at a June 23 meeting where he presented findings from a detailed report on the economics. It is imperative to expand the user base beyond the city, he said. Making the project work requires some kind of commitments from the island’s bottom-line focused seafood processors, and that could be a hard sell, he said. And it still needs to compete with diesel, now in a price slump, he said.

Even in the best of circumstances, the project’s power would be more expensive than that coming from the current diesel-burning system — in at least the first years — according to his analysis.

Hubbard’s calculations showed the need, even in the best-case scenario, for a 3-cent-per-kilowatt surcharge in those early years, which might be considered a worthwhile price to ensure the switch to geothermal energy. “It’s not like 3 cents is the end of the world or anything. It still might work if people are willing to pay a little in the early years,” he said at the June 23 meeting.

The Makushin project is just one of several geothermal-energy ideas that have emerged in Alaska.

One that was seriously pursued before sputtering out would have been at 11,070-foot Mount Spurr, the active volcano that is the closest to Anchorage, less than 80 miles to the west. Spurr has a history of explosive eruptions. The most recent, in 1992, threw ash on the state’s biggest city and surrounding communities.

In 2008, the Alaska state Division of Oil and Gas sold leases on about 36,000 acres at Spurr to Nevada-based Ormat Technologies, which was investigating the possibility of sending energy from the volcano to Anchorage. Ormat spent several years exploring the geothermal resources at Spurr but ended up dropping the project. The division continues to solicit interest in further work at Mount Spurr, and it called for applications last year.

There are other potential sources around the state for geothermal-fueled power, some being studied by the Alaska Center for Energy and Power at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

One is at Pilgrim Hot Springs, about 50 miles northeast of Nome, a one-time spa used by Gold Rush-era miners relaxing from their toils. After its tenure as a recreational retreat for miners, Pilgrim Hot Springs became the site of a Catholic Church-run orphanage serving children who had lost their parents in the 1918-19 influenza epidemic. In those days, the hot springs’ energy was used to heat greenhouses that produced food for the orphanage residents, an early version of Karl’s agricultural vision for Unalaska.

Pilgrim Hot Springs is now something of a tourist attraction and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. But it could be more than that, according to studies; the site holds a capacity for a 20-megawatt power system and could ship some of its energy to Nome or to mining operators, according to the Alaska Center for Energy and Power.

There have been some successful uses of energy stored in the ground to heat homes and buildings, notably by the Cold Climate Housing Research Center in Fairbanks and the Anchorage-based Cook Inlet Housing Authority. Though different from the traditional geothermal energy associated with volcanoes or hot springs, those building-heating systems fall in the general geothermal category.

In Unalaska, the Makushin geothermal sponsors believe that despite past false starts and current risks, their project will be the next breakthrough that switches out fossil fuels for geothermal energy.

Chris Salts, chief executive officer of the Ounalashka Corp., made that pitch at the June 23 council meeting. He spoke about his children, who’ve grown up there in “the most beautiful area of the world, the most rich fishing community of the world.”

“I cannot look at them in the eye and tell them that I did not try to clean up our mess, our diesel mess,” he told the council. “This is the time, this is the place to do this.”

If geothermal doesn’t work out, Unalaska has a potential backup. Since 2003, it has been investigating the prospects for a different source of renewable energy — wind power. That work became more serious starting in 2017, when the city hired a wind-energy contractor. In December, the council approved another $75,000 payment to the contractor, on top of about $270,000 already authorized. The contractor is using meteorological towers to gather wind data that would be used to design the appropriate turbines for the island.