A tough strategy of isolation has protected Greenland from coronavirus — so far

Greenland's geography seems to have helped it contain COVID-19. But the country still faces serious challenges from the pandemic.

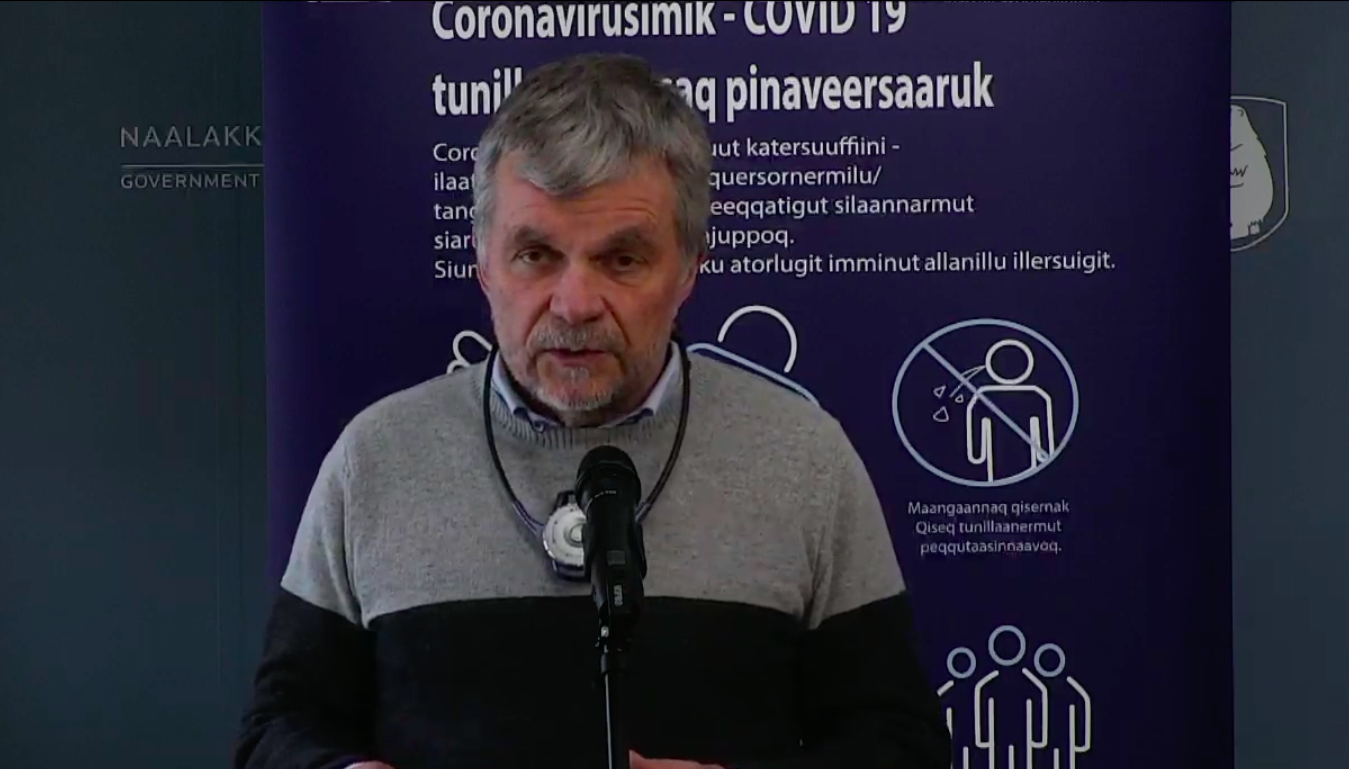

Imagine the audacity it takes to close off the largest island on Earth from the rest of the world. An impossibility, a baffling paradox, you would think, but then with coronavirus, it seemed the only way to prevent disaster. Greenland’s Chief Medical Officer Henrik L. Hansen was right in the thick of it, providing the crucial pieces of advice on a strategy of almost total isolation to the government in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital.

“Until further notice, the strategy in Greenland is to pursue a complete containment of the virus to win time,” Hansen tells me over the phone from Nuuk. “The situation outside Greenland is still completely unpredictable, and since we cannot be sure to that we can get the necessary assistance from outside, all factors at this moment say that the most sensible thing to do is to win time. It may not be sustainable in the long run. It is not likely that we can keep the disease away from Greenland for always, but that is the strategy for now.”

You are forgiven if you believed that such a strategy would be less dramatic, because Greenland is so remote anyway and not really part of the global currents of people, power and politics. But this is not so.

Greenland is very much part of the global mainstream, intricately linked to the rest of the world by the rapid movement of many people, by high-speed internet, finance and politics. You may take Greenland’s central role in U.S. security politics as just one example. Thule Air Base at the very north of Greenland is a crucial element of U.S. missile defense and it was only last year that president Donald Trump aired a wish to buy Greenland, lock and stock and people from Denmark, which still holds sovereignty over this otherwise semi-autonomous nation.

[Greenland stays optimistic while bracing for a long fight against the coronavirus]

Greenland is an important and very, very large nation of vast and open spaces, for millennia a land of wandering people who came from North America and later also from Europe. From the early days a home of intrepid nomads and today a globalized exporter of valuable seafoods, precious minerals and adventure tourism; an attraction for scores of U.S., European and Asian businessmen and tourists on planes, cruise ships, dog sleds or in trekking boots.

Its 57,000 people are dispersed over more than 2.1 million square kilometers and more than 70 towns and villages — none of which are connected by railways or roads. The upper tip of Greenland is closer to the North Pole than any other piece of land on the globe. So isn’t Greenland sufficiently protected from the pandemic simply by its remoteness? Not at all.

When the news of the coronavirus pandemic came, the authorities in Nuuk struck hard and efficiently, or, as it says on the Chief Medical Officer’s website:

“The strategy pursued by the authorities is to reduce and delay the spread of the novel coronavirus/COVID-19. The authorities will test suspected cases of COVID-19. If someone becomes infected, the source of the infection will be identified and potential disease carriers will be contacted by the health authorities.”

The strategy has been implemented in apparently fluent concert between the relevant authorities in Nuuk, encompassing Naalakkersuisut, Greenland’s self-rule government, the police and the relevant departments and officials, including Hansen, from Greenland’s small but modern health service, which is 100 percent publicly owned and financed.

The red ships of Royal Arctic Line, the national shipping company, still bring vegetables and other necessities from the south. Essential supplies continue, but for the first time ever all normal travel by ordinary people in or out of Greenland is prohibited, all normal internal air traffic have been shut down, and the authorities have extended their stern advice that all citizens who can avoid it should remain at home, not travel from one town to the other, whether on snowmobiles or dog sleds, not go from one district to the other unless absolutely necessary or with special license from the police or from Greenland’s Epidemiological Commission until at least April 30.

Nuuk, the capital, is completely shut off from the rest of Greenland. No ordinary people are allowed to enter or leave town without special permission, not even on private boats or snow scooters. Since Easter, schools outside Nuuk are gradually opening, alcohol is once again on sale in Nuuk after several weeks of prohibition, but all the main restrictions on the movement of people are still in place.

[After 11 COVID-19 infections, Greenland plans to slowly reopen Nuuk]

In consequence, Greenland now belongs to a very rare group of nations: Those without any known active cases of coronavirus.

As I type this, not one person in Greenland is believed to be infected with COVID-19, nor has anyone has been hospitalized for the illness. Since the beginning of the pandemic,11 people have tested positive in Greenland, all in Nuuk, and all 11 were quarantined and have since recovered. More than 1,000 people have been tested, but outside of Nuuk, not one person has tested positive from covid-19. The lockdown is proving impressively effective, and for now there is no plans to change tack.

Hansen, who has a staff of four, readily admits that it will of course be impossible to keep Greenland fenced off in the long run. The costs to the business community, to Greenland’s tourism industry, to its service industry, to basically every line of normal economic activity could be devastating. Greenland’s minister of finance, Vittus Qujaukitsoq, tells me over the phone from his isolation in Nuuk that he is “cautiously optimistic.” Greenland’s all-important fishing industry, which provides more than 90 percent of Greenland’s export revenues, is still intact and operating, he confirms, but sales and prices on the world market are beginning to weaken.

“Eventually everyone of us will be affected by the epidemic — especially if this goes on over the summer,” he says.

[Greenland is well-placed to weather COVID-19’s economic storm, economists say]

The strain on civil society also continues, but even when if I ask several times, I cannot make Hansen provide any predictions as to when it will be advisable to lift the isolation in earnest:

“I don’t make these kind of predictions. It makes no sense to me to try to picture how things will develop as long as there are so many unknowns. We have seen how much can change in just a week,” he says about the pandemic.

Development of a so called herd immunity, where many members of society get infected, survive and build up immunity so that it amounts to a national defense against the virus that finally protects the weaker and more vulnerable from infection, is not part of the strategy in Greenland:

“No, not with the knowledge we have to today,” says Hansen. Instead, he is looking at scenarios where COVID-19 dies out and disappears on its own, as happened with the Spanish flu in 1918, or scenarios where a vaccine against COVID-19 or better means of treatment are developed.

Twelve months?

Earlier this month, as I wrote here, a former head of Greenland’s health services, Ove Rosing Olsen, told me why fighting coronavirus takes special efforts in Greenland:

“Our capacity to deal with respiratory insufficiency is limited. If the system is overrun by too many patients with severe symptoms, many who could have been saved with the right treatment, will die. Instead of allowing the virus to spread, it is all about keeping it at bay until a vaccine is available. I believe we will have to have very little contact with others for a longer time, perhaps for another twelve months,” he said.

Hansen tells me that many elderly people in Greenland still vividly remember earlier epidemics. Hepatitis A hit hard in the 1970’s, smallpox took its toll in the 1950’s, and tuberculosis was recurrent in Greenland throughout the first half of the 20th century. Greenland’s history is ripe with diseases brought from the outside, killing scores of people, so it is perhaps not surprising that many readily embrace the strategy to isolate and stamp out the new scourge.

“For once it is to our benefit that we live so isolated,” Sara Olsvig, head of program for United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, in Greenland tells me.

“We live on 2.1 million square kilometers and we are only 57,000 so we are vulnerable but in this case we have turned it to our advantage. When you close our air traffic and the few passenger ships you have more or less closed the country completely. The authorities have also made it clear that one should refrain from travelling from one place to the other even with one’s own dog sled or boat and it seems as if people do what they are told,” she says.

Olsvig is the former leader of Inuit Ataqatigiit, Greenland’s largest opposition party, and former chair of the The Standing Committee of the Parliamentarians of the Arctic Region. She is often critical of the ruling Greenlandic government, but not right now:

“The strategy of hard containment of the virus has been really smart. An epidemic would be very difficult to handle, because our health system was under pressure even before corona,” she says from Nuuk.

Only four beds

Greenland’s only main hospital in Nuuk commands a total of four beds in its intensive care unit; Greenland’s only such intensive care options. A few more can be mobilized in an emergency, but the total number of beds, where patients can be kept alive with ventilators for any length of time is four under normal circumstances.

Add to this Greenland’s tough logistics. If a patient from any of Greenland’s many small villages outside the main towns needs intensive care, he or she must be flown to the nearest town by helicopter and then by plane to Nuuk along with the necessary medical staff — and all of this is only possible when the weather allows.

In addition, Hansen presently faces a new unexpected challenge that strengthens his resolve to keep Greenland in lockdown for now. With short notice, a surprising number of nurses and other health care workers from Denmark have cancelled arrangements to work in Greenland. To Hansen it is therefore the threatening shortage of personnel, and not the limited intensive care facilities, that presents the greatest challenge to fighting a potential coronavirus outbreak in Greenland.

“It is beginning to look critical, in particular when we talk anaesthetics and intensive care,” he tells me.

Also, he is uncertain if it will be possible in an emergency to transfer patients to Denmark if capacity in Greenland should prove insufficient, as would normally happen. He is wary of potential new — and more restrictive — regulations of air transfers of coronavirus patients from IATA, the International Air Transport Association.

Meanwhile, a new laboratory in Nuuk, established in record time, is a welcome improvement. When I call him, Hansen is just back from the new facilities that will enable testing for the virus in Greenland. So far, all tests have had to go to Copenhagen for analysis, a time-consuming process that can now be eliminated. Testing is crucial for the continued pursuit of the key goal: Total containment of COVID-19 in Greenland.