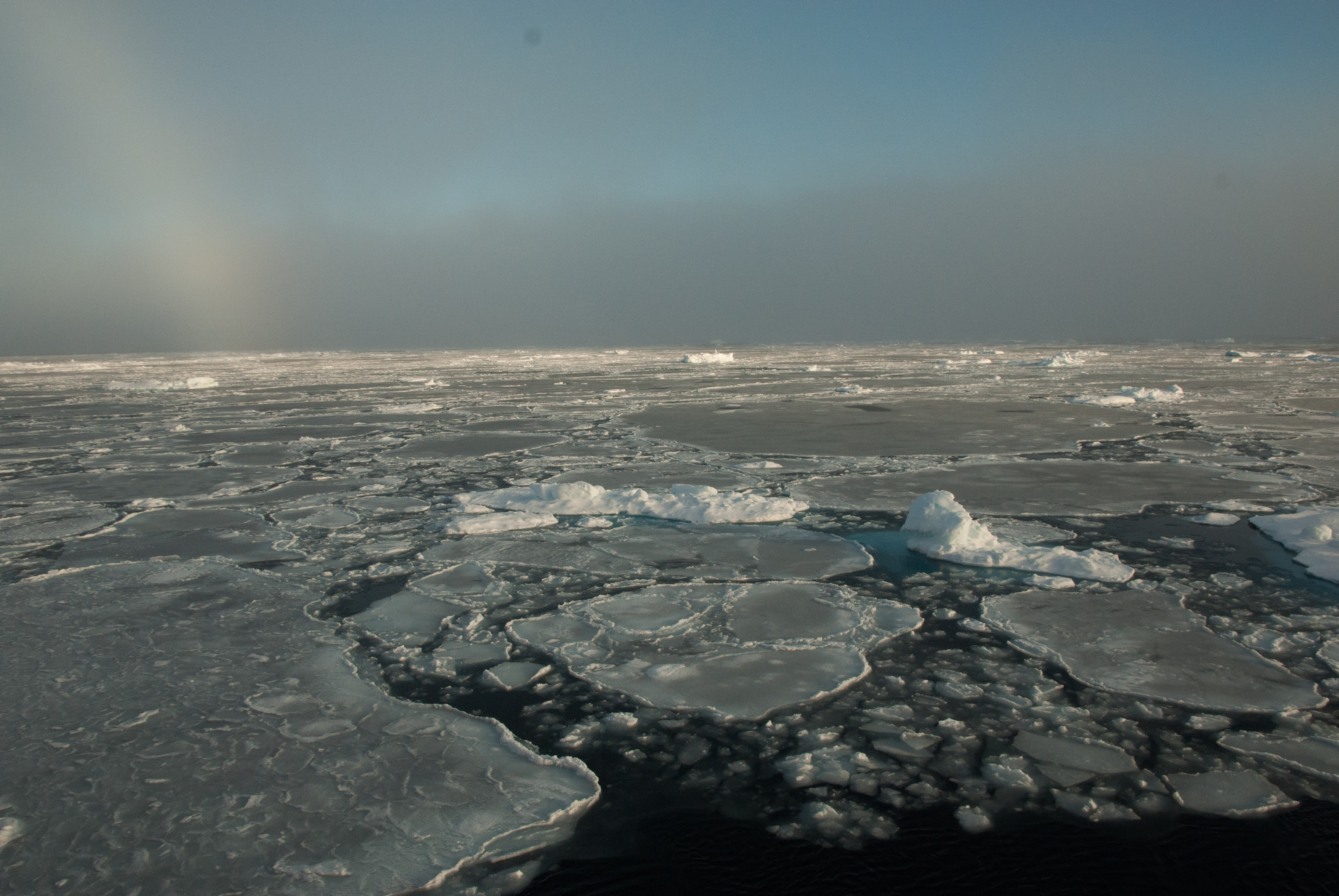

A warmer Arctic appears to be the new normal, says annual agency report

(Alek Petty / NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)

The past year, with dramatic warming in the air, in the water and on land, was a continuation of a “new normal” in the Arctic, said an annual report issued Tuesday, offering little hope the region will return to a past in which it was “reliably frozen.”

Around the north, there were “pervasive changes in the environment” over the past year, said the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s annual Arctic Report Card.

“While fewer anomalies were recorded this year, we see no sign of the Arctic returning to the stable conditions we saw in the past,” said Jeremy Mathis, director of NOAA’s Arctic research program, at a press conference unveiling the report at the annual gathering of the American Geophysical Union in New Orleans.

“Changes that are happening in the Arctic will not stay in the Arctic,” Mathis said. “These changes will impact all of our lives. They will mean living with more extreme weather events, paying higher food prices and dealing with the impacts of climate refugee.”

Arctic warming affects lower latitudes as melting ice sheet threatens to trigger “catastrophic sea level rise,” while a warmer Arctic atmosphere and ocean can disrupt the jet stream, which drives weather patterns far south of the Arctic.

“The Arctic is going through through the most unprecedented transition in human history, and we need better observations to understand and predict how these changes will impact everyone, not just the people of the north,” Mathis said.

Marine waters warmed, wide swathes of sea ice vanished, plankton bloomed in far-north waters in far greater densities than in the past, green plants proliferated over the tundra and temperatures of frozen soil beneath the earth’s surface inched up closer to the thaw point, said the report.

The report, the work of 85 researchers in 12 countries, analyzes environmental conditions in the Arctic, a region warming twice as fast as the global average. It examines conditions in the ocean, the pace of melt on ice sheets, the extent of summer green-up on the Arctic tundra and other aspects of the rapidly changing natural environment.

That analysis revealed numerous record or near-record measurements around the Arctic in 2017.

Above Latitude 60, the average surface air temperature from October 2016 to September 2017 was the second warmest ever measured since 1900 — second only to the temperature recorded the year before.

The maximum extent of Arctic sea ice, formed after a full winter of freeze, was the lowest in the satellite record that goes back to 1979, the report noted. While melt of summer sea ice was slowed by some cool weather, 2017 still had the 8th lowest annual minimum in the satellite record, an extent 25 percent lower than the 1981-2010 average and made up of predominately thin and new ice. Only 21 percent of the 2017 ice cover was more than one year old, compared to 45 percent in 1985, the report said.

In many areas of open water, temperatures shot well above past levels. Warming in the Chukchi Sea off northwest Alaska was especially pronounced, with temperatures up to 4 degrees Celsius warmer than the 1982-2010 average. Warm water temperatures led to prolific plankton blooms and elevated ocean productivity.

Paleoclimate analysis that reconstructs conditions millions of years into the past indicates that Arctic sea ice decline and warming of the Arctic Ocean’s surface is happening at a pace “unprecedented in at least the last 1,500 years and likely much longer,” the report said.

On land, permafrost temperatures at several areas around the Arctic the highest on record, according to 2016 measurements, the most recent data available. The biggest increases were in northern Alaska, Canadian High Arctic and Svalbard, the report said. On Alaska’s North Slope, which holds some of the United States’ biggest oil fields, permafrost temperature readings 20 meters below the surface were the highest ever recorded at all but one of the sites monitored by scientists. Even in interior Alaska, where permafrost temperatures had held steady during the first decade of the 21st century, the below-surface soils are again getting warmer, the report said.

Warming permafrost below ground poses dangers for people who live and work on the ground’s surface, said Vladimir Romanovsky of the University of Alaska Fairbanks and lead author of the report’s permafrost section.

“Warming permafrost is having profound effect on communities where houses are sinking, roads are collapsing and other infrastructure is being severely damaged,” he said. “The other significant effect is that as permafrost thaws, it gives off greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide and methane.”

More greenhouse gases, produced when ancient carbon is mobilized by thaw, add to the load already created by fossil fuel burning and contribute to the layer that holds in the planet’s heat.

Not all 2017 Arctic indicators were on the warm side.

Thanks to some relatively cool weather, the May snow cover extent was the second highest in the satellite record that goes back to 1967, and Eurasia in May and June had its first positive anomalies for snow cover since 2005 and 2004.

There was also unusually slow melt of the Greenland ice sheet. The ice sheet has lost mass at the rate of 264 to 270 gigatons a year over the past 15 years, but this year’s maximum spatial extent for summer melt — 32.9 percent of the ice sheet — was the lowest since 1996.

Arctic Now’s Kevin McGwin contributed to this report.