After a stronger freeze season, melting is again underway for Arctic sea ice

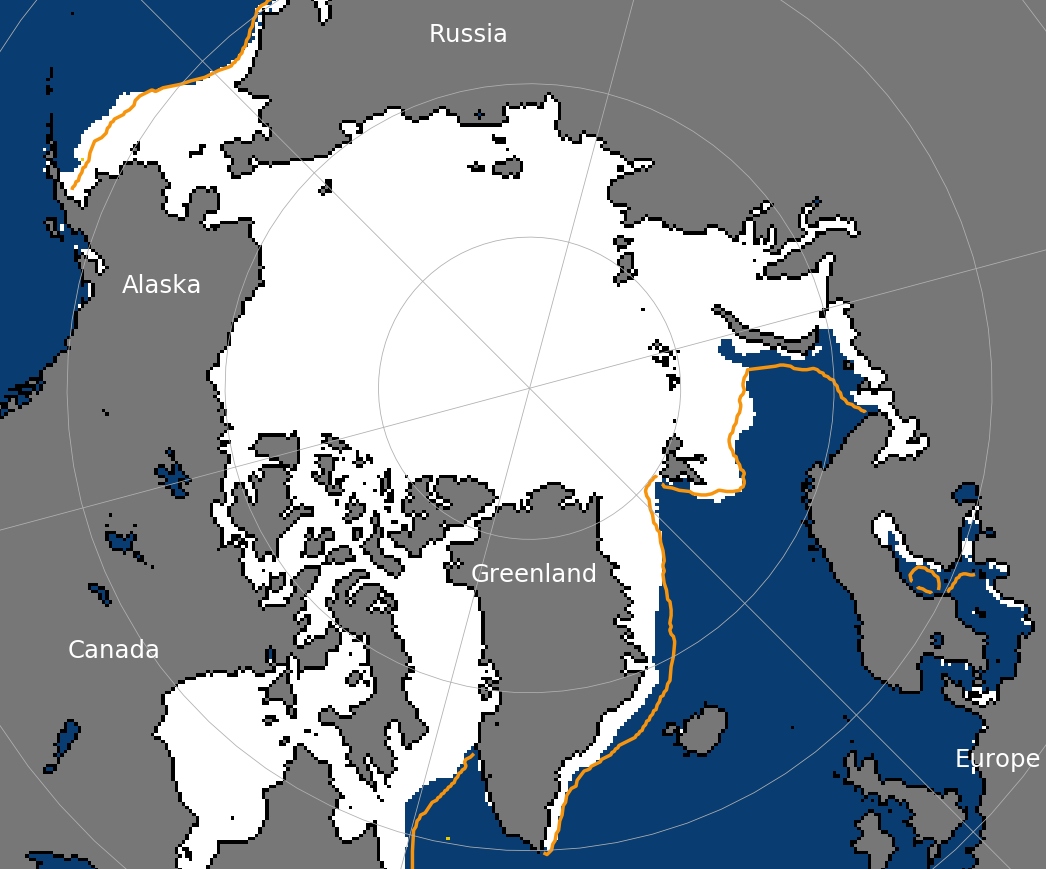

While still below the 1980-2010 average, sea ice was more extensive than it has been for the last several winters.

The 2020 melt season is underway in the Arctic after a winter during which some persistently cold weather that allowed the maximum extent to rebound from recent winter maximums that reached or near record lows.

The maximum freeze extent was likely reached on March 5 and was the 11th lowest maximum extent in the 42-year satellite record, the National Snow and Ice Data reported Tuesday. It was the largest maximum extent since 2013, a change from recent years’ low maximums.

“It’s not an extraordinary year. It’s not a headline year, by any means,” said Walt Meier, an NSIDC scientist.

The 2020 maximum extent was 15.05 million square kilometers (5.81 million square miles), still below the 1981-2010 average of 15.64 million square kilometers (6.04 million square miles) but well above the record-low maximum of 14.41 square kilometers (5.56 million square miles) that was set in 2017, the Colorado-based NSIDC said.

The March 5 maximum date comes a week earlier than the median over the 1981-2010 period, according to the NSIDC.

A persistent positive Arctic Oscillation, with low air pressure centered over the Arctic and higher air pressure over the northern Atlantic and Pacific, kept temperatures cold for an extended period and helped ice extent grow substantially in February.

The departure from the previous years’ low was “just the year-to-year internal variability,” Meier said.

Do not expect this winter’s freeze-up to help predict the summer’s melt, Meier and other NSIDC scientists advise.

While both summer and winter ice extents are trending down over time, there does not appear to be any link between individual winters’ maximum ice extent and the end of the melt seasons that follow half a year later, NSIDC scientists have found.

It might seem that a higher winter freeze would set up for a slower and less extensive melt season, “but it looks like there’s really no correlation,” said NSIDC Director Mark Serreze.

In 2012, for example, the maximum winter freeze extent was high compared to recent years, but after the following summer and fall, extent fell to the lowest level in the satellite record, by far.

At one time, a steady positive Arctic Oscillation pattern like the one that persisted this winter might have indicated events to come in the melt season, Serreze said.

Such patterns used to be followed by big melt seasons and lower ice minimums because of the way they moved ice through the Fram Strait, he said. “In the past, it flushed old ice out of the Arctic Ocean. Well, there’s not a lot of old ice anymore,” he said. “The goalposts are shifting.”

For the Bering Sea, which in past years has had mid-winter melts and low winter ice, followed by extraordinary ecological consequences, this year’s freeze-up was a notable change. Winter freeze extent even exceeded the satellite-era average for a brief period. That is thanks to the lack of southern winds that blew in over the recent winters, Meier said.

But those southern winds have returned in the past couple of weeks, bringing warmth and melt to the Bering. As of March 24, about 30 percent of the Bering’s ice extent had vanished over an 11-day period, according to NSIDC records.

The incursion of warmth and a rapid melt took a toll on the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. Three mushers who were nearing the Nome finish line had to be rescued by helicopter on March 20 near the checkpoint of Safety — the final stop that is 22 miles before the finish of the 1,000-mile race — after they became submerged in deep water that had flooded the trail, surging in from the Bering Sea.

The rescued mushers — Sean Underwood, Tom Knolmayer and Matthew Failor — scratched from the race. For the 11 mushers after them, Iditarod officials re-routed the trail into a longer route that traveled inland. The final musher reached Nome on March 22.