After the latest elections, the Danish Kingdom’s Arctic votes are suddenly decisive

Post-colonial dilemmas are surfacing as the balance of power in Copenhagen hinges on members of parliament from Greenland and the Faroe Islands.

Not since Donald Trump’s flamboyant 2019 vision of a U.S. takeover of Greenland, the world’s largest island, has the Kingdom of Denmark’s unique postcolonial construct demanded so much attention of the Danes themselves.

In 2019, the strength of the union between Denmark and Greenland was tested by the sudden move by then-President Trump. Now, after general elections that were held in Denmark on November 1, the kingdom’s internal relations have once again come under renewed scrutiny.

Since the election, three North Atlantic members of the Danish parliament — two from Greenland, a former Danish colony, and one from the Faroe Islands, a semi-autonomous group of 18 islands in the North Atlantic — have held the power to decide who will lead the government in Copenhagen for the next four years.

I can assure you that this is not a common situation in Copenhagen, the Kingdom’s capital, from where I write, and on the fringes of the furor that this situation has provoked in some quarters, thoughts of possible changes to our constitution are now being aired.

Arctic power

Although the situation is unusual, everything is happening according to carefully elaborated rules and procedures constructed to keep the Danish Kingdom inclusive and operating like a well-oiled machine. Even if there is more than 3,500 kilometers separating Copenhagen from Nuuk, Greenland is still — like the Faroe Islands — a part of the kingdom (unlike Iceland, which severed its last formal ties to the Danish king in 1943 and became a fully independent sovereign republic).

As we digest the peculiar details of the present, many Danes have been forced to revisit our old relations to the Faroe Islands and Greenland and to recount why it is that a tiny number of votes, cast by people who live far away in the Arctic and who speak their own separate languages, can suddenly hold such sway over our national politics.

The basic question, of course is whether it is still fair and good that the peoples of Greenland and the Faroe Islands have such powers?

Are the old rules and procedures, established in another era, still legitimate and sufficiently reflective of our values and ideals?

As one of our former prime ministers, the liberal Lars Løkke Rasmussen quipped on television in the late hours of the election night as he licked his electoral wounds:

“If you look at Denmark — not the Danish realm, but Denmark — there is no red majority. Only because of the way the votes fall in Greenland is there a red majority,” he said.

Others followed suit. Nobody questioned openly the electoral system that allows the North Atlantic members of the Danish parliament their powers, but the electoral campaign had already revealed how Danish politicians will at times lack respect for their North Atlantic counterparts.

One contender for the office of the prime minister, the conservative leader Søren Pape Poulsen, was quoted during the campaign as remarking that “Greenland is just Africa on ice,” a slur allegedly aired during a visit to the U.S. Embassy in Copenhagen. Poulsen had to apologize to the people of Greenland on prime time TV while a roar of dissatisfaction made its way from Nuuk.

Laws and tradition

Many Danes would be unable to remember the full explanation as to why voters in the Faroe Islands and in Greenland can suddenly wield such influence over the political process in Denmark.

As our constitution was put in place in 1849, the Faroese were considered part and parcel of Denmark’s cultural and historic realm. There were less than 10,000 people living on the islands at the time. Moreover, the islands were steered by Danish officials, the islanders spoke (and still speak) a Nordic language, and as a new parliamentary system was established on the basis of the Kingdom’s new constitution, the Faroese were guaranteed the right to elect two members of parliament.

In 1953, following a national referendum in Denmark (but not in Greenland), the constitution was revised and an end was put to Greenland’s colonial status. Greenland was turned instead into a fully integrated part of the Danish Kingdom and those who lived in Greenland became, like the Faroese, Danish citizens.

As all legislation pertaining to Greenland came from Denmark, Greenland was accorded the same right to elect two members of parliament.

The four North Atlantic members have since been counted as fully mandated members of parliament in Copenhagen. They carry exactly as much or as little political weight and influence as the 175 other members of parliament — and this is all stipulated by the constitution.

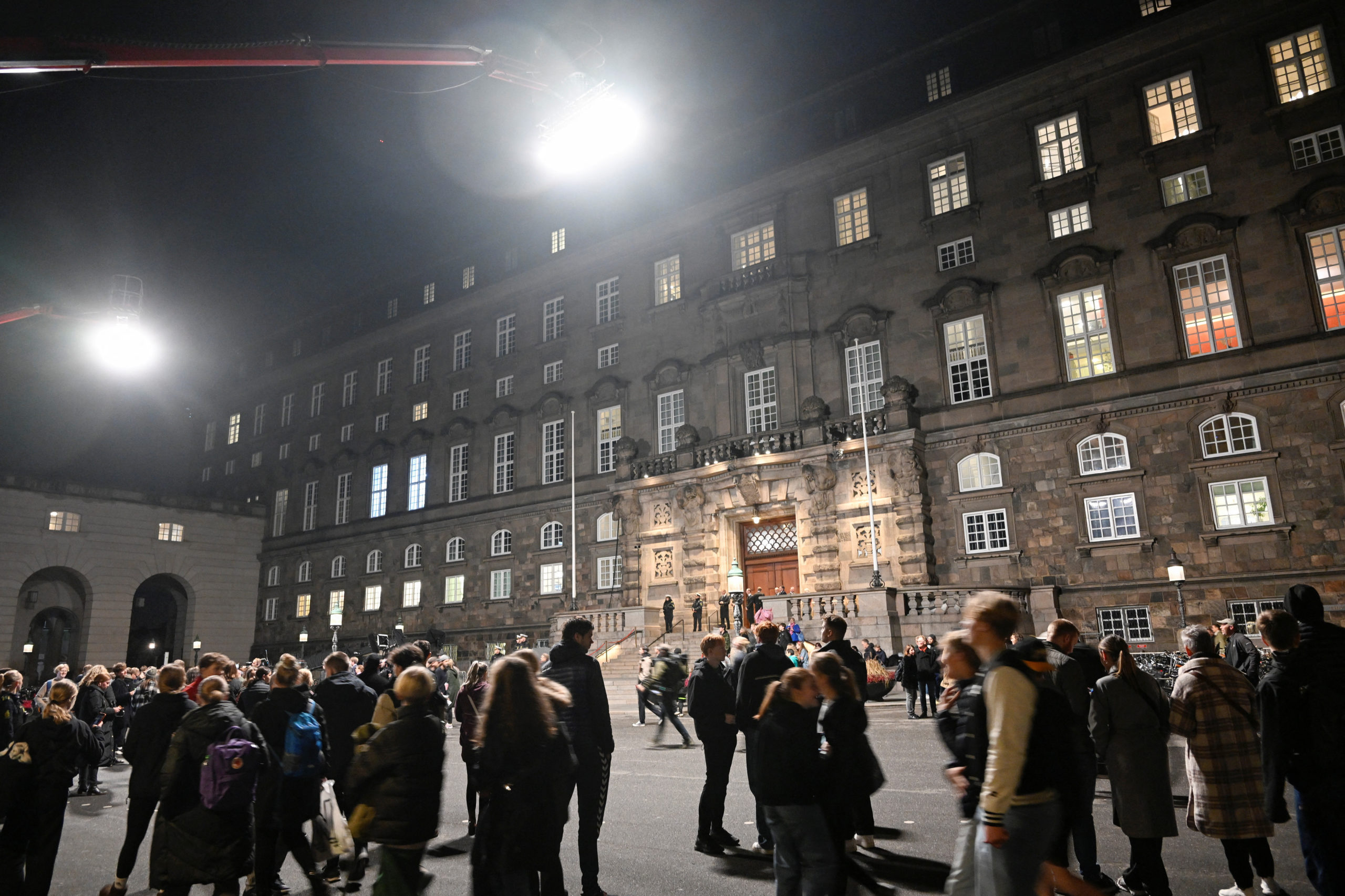

Most of the year, the efforts of these four members of parliament raise few alarms. The media, the public and most Danish politicians seldomly concern themselves with the affairs of Greenland or the Faroe Islands, but then — boom — suddenly, as in these days, the four extra votes may become crucially important as a majority in the Folketing, Denmark’s parliament, is needed to form a new government.

Tiny votes

This is then the resulting state of affairs: As I write this on Tuesday, a struggle for the central hold on political power in Denmark hinges on three politicians from Greenland and the Faroe Islands, who have chosen to support the efforts of Mette Frederiksen to form a new government.

Behind them stand relatively small numbers of voters. The two from Greenland received 4,289 (Aaja Chemnitz) and 6,655 votes (Aki-Mathilda Høegh-Dam). That is, from a Danish perspective, not a lot of people, and as the media in Denmark have been careful to report, more than half of the electorate in Greenland did not even take part in the elections. Most people in Greenland seem to care more about who holds power in Inatsisartut or Naalakkersuisut, the parliament and government in Greenland, respectively.

Sjúrður Skaale, the Faroese, won 3,804 votes at the polls in the Faroe Islands. In total, less than 15,000 voters invested in these three politicians, but if only one of them changes his or her mind tomorrow, the political situation in Copenhagen will be turned on its head. Somebody other than Frederiksen will win the power to lead negotiations to form the next government.

Unreasonable?

While we wait for the results, Frederiksen, a Social Democrat and acting prime minister, has won the mandate to lead the negotiations.

At the elections, her Social Democratic party and the center-left parties that support her won exactly 90 seats or a marginal majority of the 179 seats in parliament, but only if you include the three members from the North Atlantic who have chosen to support her.

We have to look back to a general election in 1998 to find a similar situation. The Danish prime minister of those days won another four years in office only through the support of a single politician from the Faroe Islands. The balance tipped when the Faroese support was declared on TV late into election night.

To top up the current turmoil, Sjurdur Skaale, the Faroese Social Democrat now re-elected into key position, argues that his own immediate hold on power is both undemocratic and illegitimate.

In and op-ed for JyllandsPosten, one of Denmark’s main media outles, he wrote last week:

“When a legitimate, democratic election leads to a result that is unfair and illegitimate, there is something wrong with the very system.”

“When many now find it problematic that I and the two Greenlandic members of parliament decide who will be prime minister, it confirms this very grave condition: The constitutional provisions for the four North Atlantic members might undermine Danish democracy.”

Outdated constitution

Skaale’s main point is that the Faroe Islands of today is a very different nation from the Faroe Islands of 1851, when the first Faroese politicians took their seats in the newly established parliament in Copenhagen.

In those days, the legislators in Copenhagen coined basically all legislation pertaining to the Faroe Island, and most people found it natural that Faroese politicians took part in the legislative process.

Today, as Sjurdur Skaale is at pains to explain, the kingdom works in radically different ways.

“The political development has led us far beyond the legal boundaries of the constitution. If the constitution is a size 42 shoe, the Danish realm is a size 47 foot,” Skaale writes.

Today, most legislation for the Faroe Island is designed and decided on by Lagtinget, the Faroese parliament, and Landsstyret, the Faroese government in Torshavn, just as most legislation in Greenland is designed and decided by Inatsisartut, Greenland’s parliament, and Naalakkersuisut, Greenland’s government in Nuuk. The role of Folketinget has been greatly reduced.

“I now hold a seat in a parliament that does not legislate for the voters who have elected me,” Skaale wrote. He also finds it wrong that he can influence Danish legislation that will put burdens on Danes in Denmark, even if the Danish electorate cannot pay him back:

“Through the fiscal bill I can lay burdens on citizens who cannot punish me at the next elections. They cannot reach me. I am elected in another country,” he wrote.

Skaale has advocated an update to the Danish constitution for some time, but he has been unable to raise any sizeable support in Copenhagen and there is little support for his view in Greenland: “I see no reason to devalue the worth of our mandate. It is described in the constitution,” Aaja Chemnitz, one of the two re-elected members from Greenland told me a few days ago. She is currently using her suddenly swollen influence to push for, for instance, quick implementation of the largest ever investigation into possible Danish wrong-doings in Greenland, a project that was agreed prior to the elections.

Last year, when Skaale tried to win support for his views in Folketinget, Prime Minister Frederiksen answered with a dismissal:

“The four North Atlantic members of Folketinget bring something very, very important — a focus on the conditions that pertain in particular to the Faroe Islands and Greenland, but also to the combined efforts of the realm. I have no problems with or and suggestions for changes to the conditions under which we work.”

This article has been fact-checked by Arctic Today and Polar Research and Policy Initiative, with the support of the EMIF managed by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Disclaimer: The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the author(s) and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.