Alaska on fire: Thousands of lightning strikes and a warming climate put Alaska on pace for another historic fire season

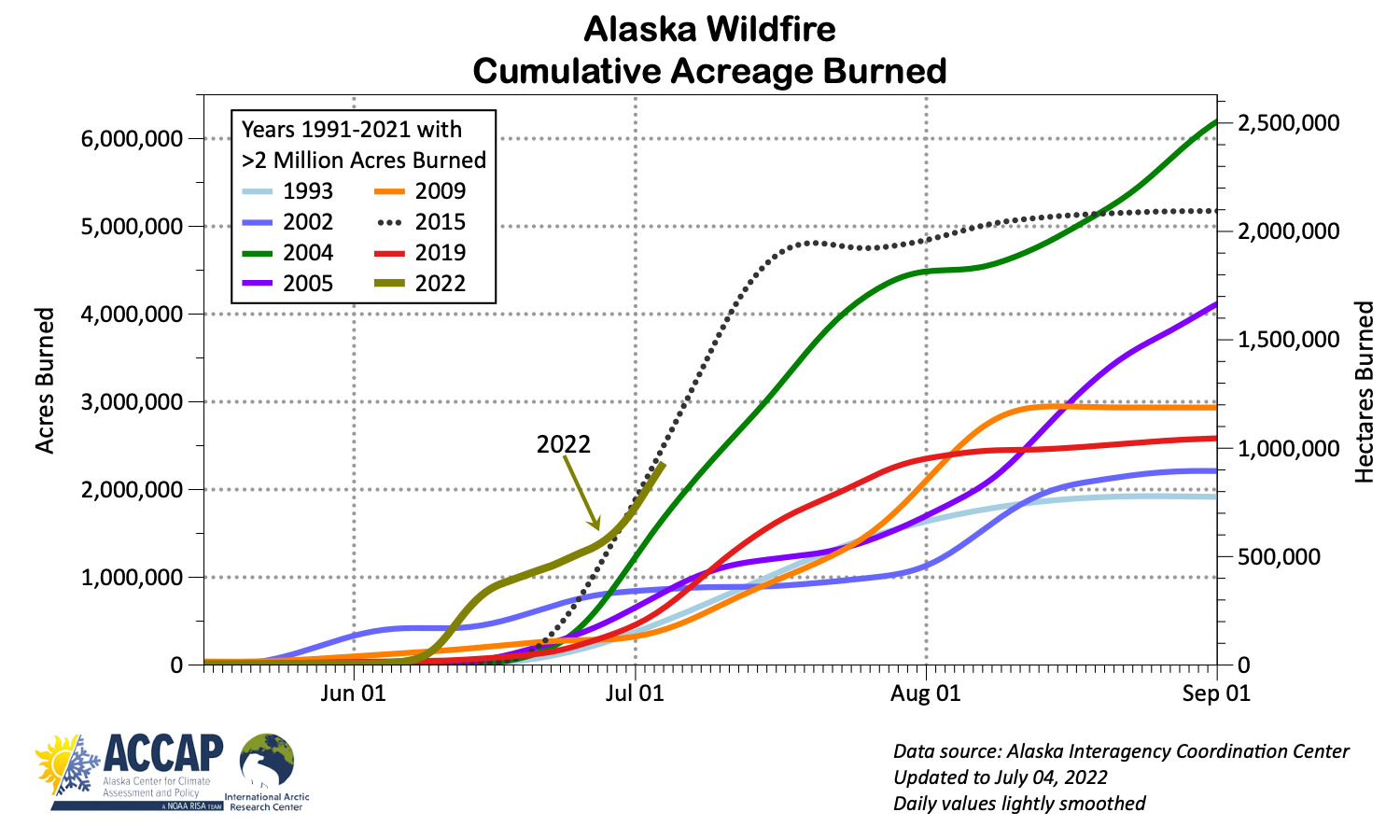

By early July this year, more that 2 million acres in Alaska had burned — more than twice the acreage of a typical Alaska fire season.

(John Kern / BLM Alaska Fire Service / Incident Management Team)

Alaska is on pace for another historic wildfire year, with its fastest start to the fire season on record. By mid-June 2022, over 1 million acres had burned. By early July, that number was well over 2 million acres, more than twice the acreage of a typical Alaska fire season.

Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at the International Arctic Research Center in Fairbanks, explains why Alaska is seeing so many large, intense fires this year and how the region’s fire season is changing.

Why is Alaska seeing so many fires this year?

There isn’t one simple answer.

Early in the season, southwest Alaska was one of the few areas in the state with below normal snowpack. Then we had a warm spring, and southwest Alaska dried out. An outbreak of thunderstorms there in late May and early June provided the spark.

Global warming has also increased the amount of fuels — the plants and trees that are available to burn. More fuel means more intense fires.

So, the weather factors — the warm spring, low snowpack and unusual thunderstorm activity — combined with multidecade warming that has allowed vegetation to grow in southwest Alaska, together fuel an active fire season.

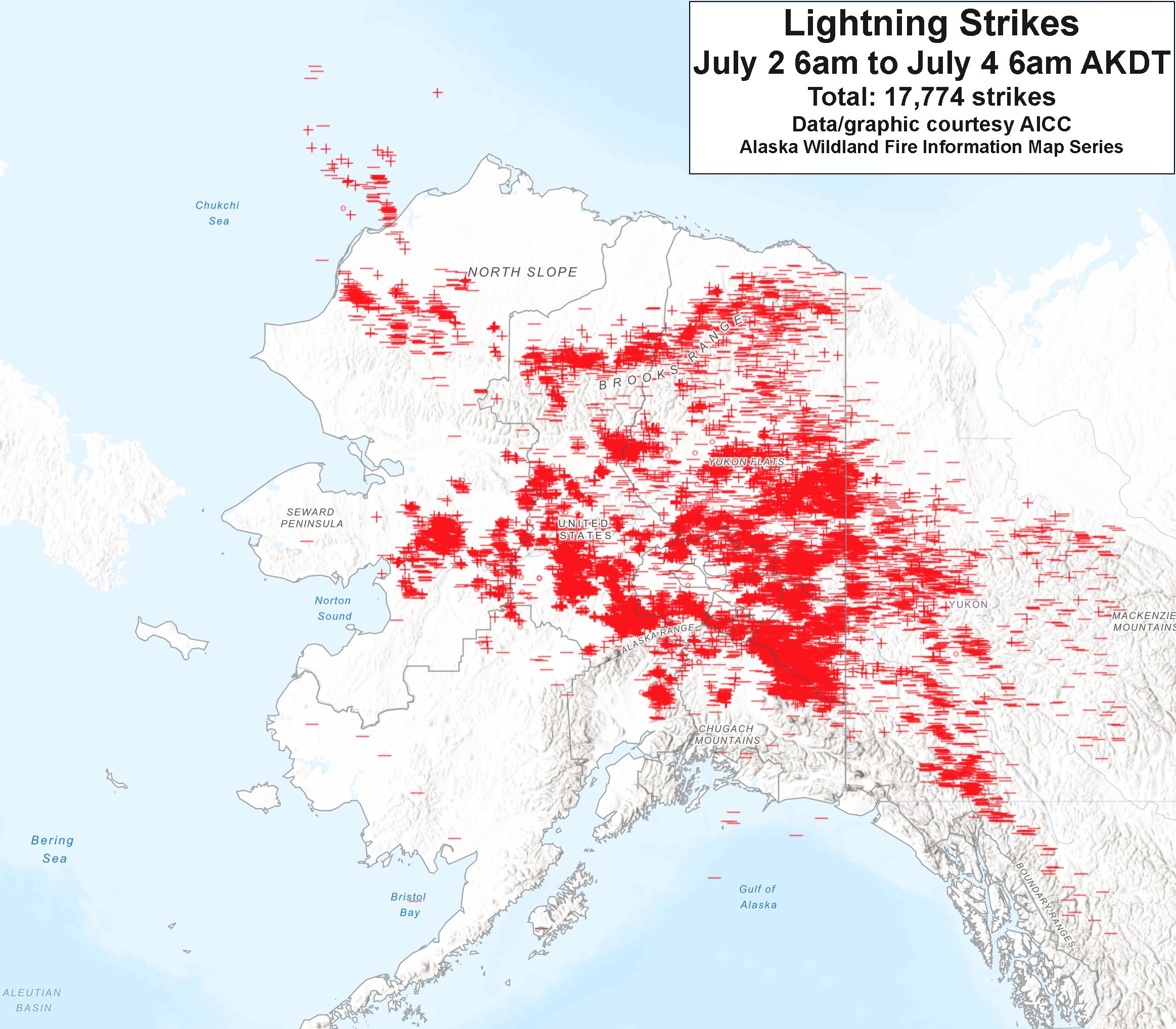

In Alaska’s interior, much of the area has been abnormally dry since late April. So, with the lightning storms, it’s no surprise that we’re now seeing many fires in the region. The interior had about 18,000 strikes over two days in early July.

Are lightning storms like this becoming more frequent?

That’s the million-dollar question.

It’s actually a two-part question: Are thunderstorms occurring more often now in places that used to rarely get them? I think the answer is unequivocally “yes.” Is the total number of strikes increasing? We don’t know, because the networks tracking lightning strikes today are far more sensitive than in the past.

Thunderstorms in Alaska are different from in most of the lower 48 in the sense that they tend to not be associated with weather fronts. They’re what meteorologists call air mass or pulse thunderstorms. They’re driven by two factors: the available moisture in the lower atmosphere and the temperature difference between the lower and middle atmospheres.

In a warming world, air can hold more moisture, so you can get intense storms. In interior Alaska, we’re getting thunderstorms more frequently. For example, the number of days with thunderstorms recorded at the Fairbanks Airport show a clear increase. Indigenous elders also agree that they’re seeing thunderstorms more often.

You mentioned hotter fires. How are wildfires changing?

Wildfire is part of the natural ecosystem in the boreal north, but the fires we’re getting now are not the same as the fires that were burning 150 years ago.

More fuel, more lightning strikes, higher temperatures, lower humidity — they combine to fuel fires that burn hotter and burn deeper into the ground, so rather than just scorching the trees and burning the undergrowth, they’re consuming everything, and you’re left with this moonscape of ash.

Spruce trees that rely on fire to burst open their cones can’t reproduce when the fire turns those cones to ash. People who have been out in the field fighting fire for decades say they’re amazed at the amount of destruction they see now.

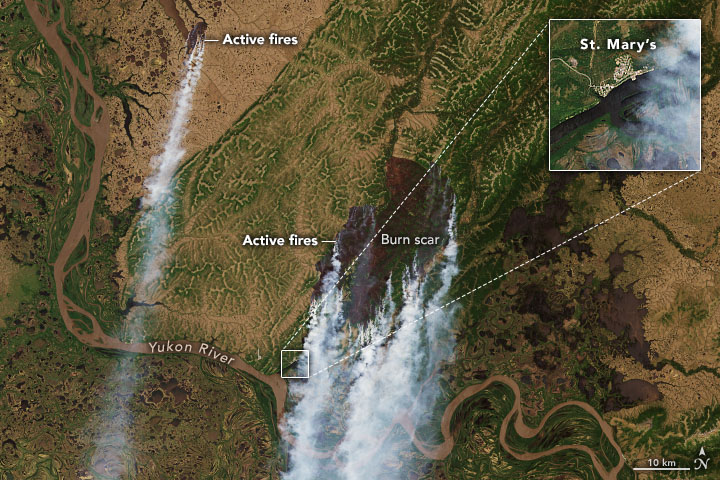

(Bryan Quimby / Alaska Incident Management Team)

So while fire has been natural here for tens of thousands of years, the fire situation has changed. The frequency of million-acre fires in Alaska has doubled since before 1990.

What impact are these fires having on the population?

The most common impact on humans is smoke.

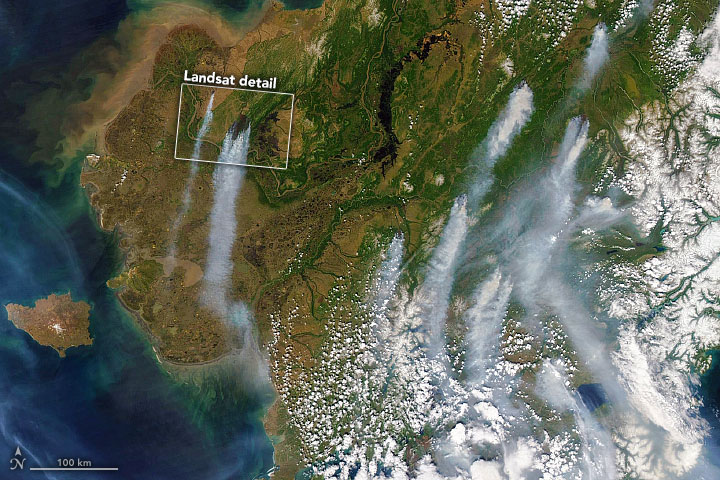

Most wildfires in Alaska aren’t burning through heavily populated areas, though that does happen. When you’re burning 2 million acres, you’re burning a lot of trees, and so you’re putting a lot of smoke into the air, and it travels long distances.

In early July, we saw explosive wildfire activity north of Lake Iliamna in southwest Alaska. The winds were blowing from the southeast then, and dense smoke was transported hundreds of miles. In Nome, 400 miles away, the air quality index at the hospital exceeded 600 parts per million for PM2.5, fine particulate matter that can trigger asthma and harm the lungs. Anything over 150 ppm is unhealthy, and over 400 ppm is considered hazardous.

(NASA Earth Observatory)

There are other risks. When fires threaten rural Alaska communities, as one did near St. Mary’s in June 2022, evacuating can mean flying people out.

Worsening fire seasons also put pressure on firefighting resources everywhere. Firefighting is expensive, and Alaska counts on fire crews, planes and equipment from the Lower 48 states and other countries. In the past, when Alaska had a big fire season, crews would come up from the Lower 48 because their fire season was typically much later. Now, wildfire season there is all year, and there are fewer movable resources available.

Rick Thoman is an Alaska Climate Specialist at University of Alaska Fairbanks.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.