Alaska’s political climate will need to change — and quickly — as the world warms

OPINION: While the world awakes to the the urgency of fighting climate change, Alaska's new official climate action plan sidesteps hard decisions.

While the authors of the recent Alaska climate action plan say they wanted to balance “aspirational goals and feasible implementation,” there is far more of the former than the latter in their final report.

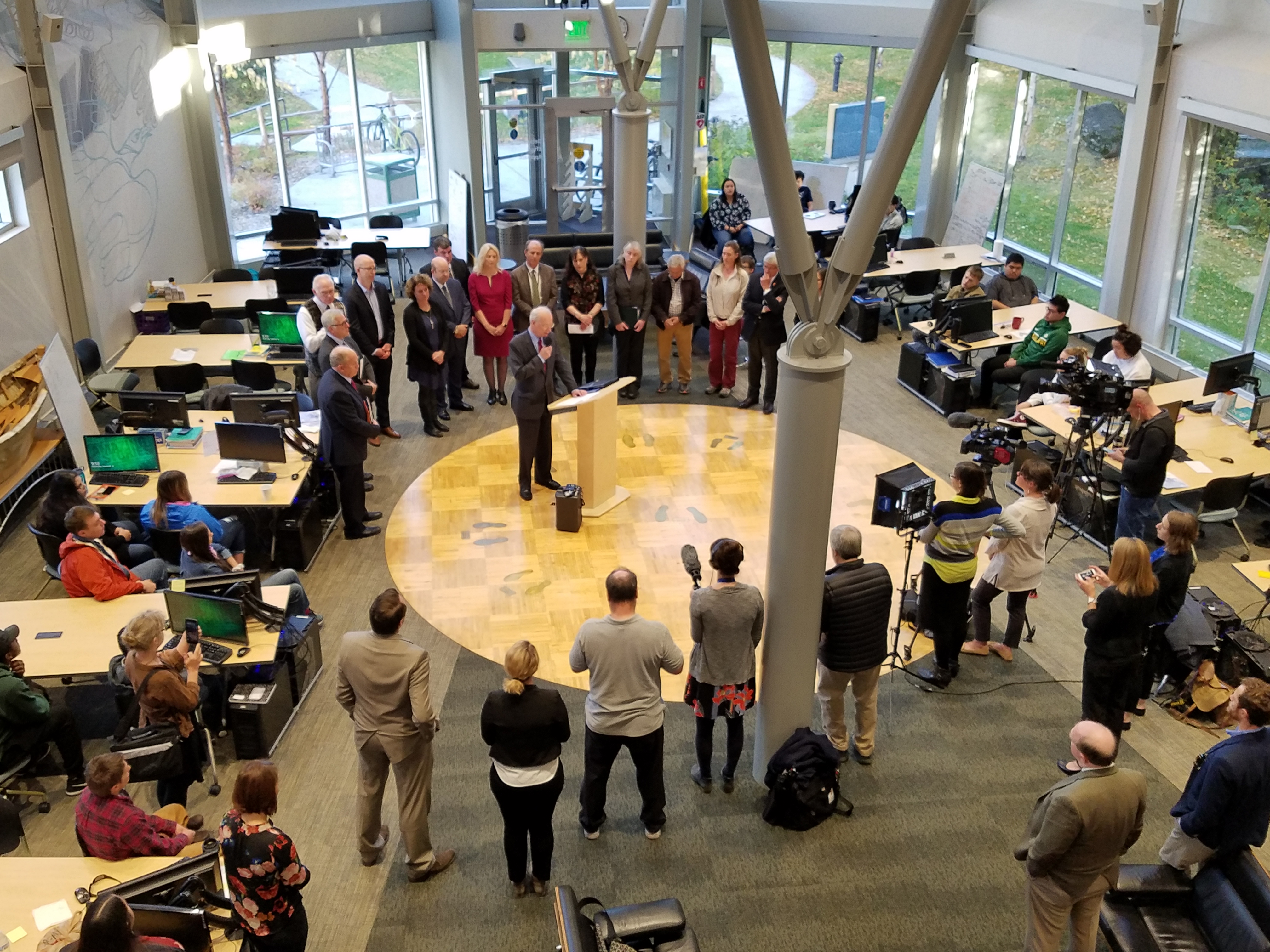

The 21 Alaskans on the panel that drafted the plan called on the state to promote renewable energy projects, reduce carbon emissions and direct government resources to help Alaskans adapt to rising temperatures, melting permafrost and increased erosion.

This comes at a time when the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” are needed to avoid a planetary disaster.

The Alaska report calls for planning, preparation, partnerships, research and leadership, but not for immediate changes in all aspects of society.

[Alaska climate team’s plan seeks to fill void left by federal government]

It is heavy on bureaucratic language that leaves plenty of wiggle room in Alaska for those trying to translate it into clear English.

The lack of clarity is understandable because there is no simple set of steps that will “stop or slow the rate of climate change,” while “sustaining a robust economy.”

There will be political and economic conflicts every step of the way because so much of the Alaska economy is based on energy production and consumption.

For example, the authors recommend that industrial operations in Alaska need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent over the next 12 years, a concrete goal.

But then they back away from that statement by adding that Alaska’s economy and state budget depend on remaining competitive worldwide: “Any approach to decreasing emissions within the oil and gas industry should account for the associated economic impact and mitigate negative financial impacts to the greatest extent possible.”

The report calls for research on ways to reduce methane emissions on Alaska’s Arctic Slope and an investigation of whether building a new efficient power plant is warranted at Prudhoe Bay.

All in all, the final report leans more toward planning than action because the economic and technical research needs to be finished before the policy tradeoffs come into clear focus.

The task force did not call for a reduction in oil and gas development in Alaska or directly address the climate change contradiction raised by an economy that remains heavily dependent on petroleum.

[Climate plan or no, don’t expect Alaska to stop drilling for new oil and gas]

“Alaska’s oil and gas industry is resilient, and is composed of global energy companies that are able to invest in and ensure the longevity of their energy profiles, which include oil and gas as well as renewable resources. The size and quality of Alaska’s oil and gas deposits will continue to attract and sustain industry investment, and the State should work with industry to ensure global competitiveness,” the group said.

The report backs the development of the immense North Slope natural gas reserves as a “bridge fuel” with lower carbon emissions than other energy resources.

It also sees potential to using Alaska public lands for carbon sequestration, which many scientists see as a must if the world is to slow the rate of warming. This could have the added benefit of generating revenue that could help the state.

Perhaps the most controversial recommendation is to evaluate a “carbon fee and dividend program” under which the state would put a tax on energy resources at the source.

“Since Alaska is a state where massive amounts of carbon-based fuel are taken out of the ground, a carbon tax would be levied on far more carbon-based fuel than Alaskans consume themselves. This is a potential advantage of a carbon tax that Alaska has over other states and nations,” the group said.

The tax could be accompanied by a dividend paid to residents with a median income or below to reduce its economic impact.

Any carbon tax proposal would also trigger industry opposition that it would make Alaska uncompetitive and prompt companies to invest elsewhere — familiar claims that arise whenever any tax is on the table.

The risks posed by a state tax on carbon would need to be understood and examined in advance. That is true with almost every specific recommendation in the report.

As to what happens next, perhaps the best way to look at this effort is to realize that in Alaska there is a strong element in the Republican Party that claims — with no evidence — that climate science is a scam.

The state is not ready to act on climate change policies, even with the latest warnings about rapid temperature changes, but this effort will be worthwhile if Alaska leaders digest its contents and do what they can to start to change the political climate.

Otherwise it will be a repeat of a similar planning effort more than a decade ago under former Gov. Sarah Palin that concluded with a report that the state filed away and forgot.

It’s much too late to pretend climate change isn’t happening.

Columnist Dermot Cole can be reached at de*********@gm***.com.