An unusual skull turns out to be the offspring of a beluga and a narwhal

DNA analysis confirmed a long-held suspicion that the two whale species could hybridize.

What do you get when you cross a beluga and a narwhal?

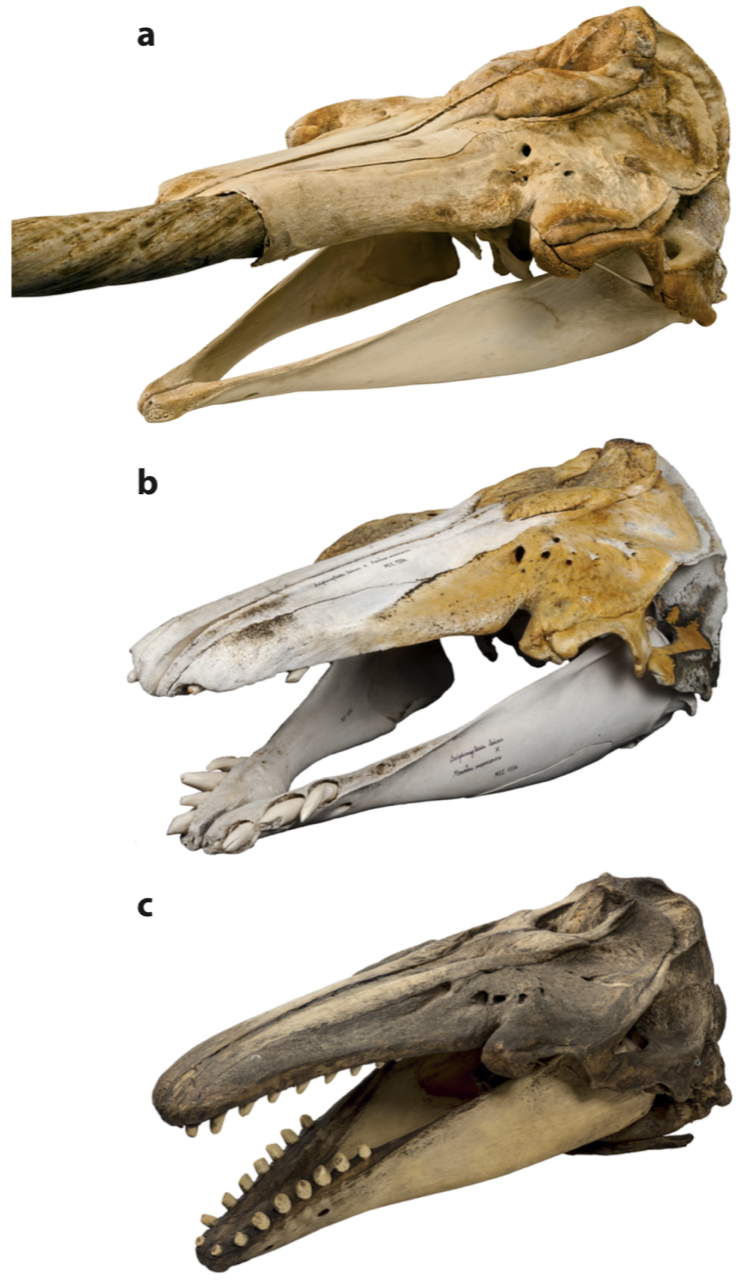

The answer is not the punchline to a classic Arctic joke. In 1990, Danish biologist Mads Peter Heide-Jørgensen found a very unusual skull on the roof of an Inuit hunter’s toolshed in West Greenland. It looked somewhat like a beluga whale, but was unusually large and robust. It also had very strange teeth. Some of the teeth in the lower jaw were corkscrew-like and some of the teeth in the upper jaw were long and pointed forward, resembling miniature tusks.

In 1993, Heide-Jørgensen proposed that this skull may have belonged to a beluga-narwhal hybrid because of its unusual appearance. The skull’s characteristics were intermediate between the beluga and the narwhal, which are the only toothed whale species that are endemic to the Arctic.

Skull analysis

The skull sat in the collections of the Natural History Museum of Denmark until my collaborators at the University of Copenhagen, Eline Lorenzen and PhD student Mikkel Skovrind, applied DNA techniques to test whether or not this skull was in fact a hybrid. Through the application of high resolution, next-generation sequencing techniques, studies of ancient DNA are revolutionizing the way we understand the evolutionary history of various species including our own.

By comparing the nuclear DNA of this unusual specimen to a reference panel of belugas and narwhals, our study demonstrated that this unusual skull did in fact belong to a first-generation male hybrid.

The analysis of the DNA from this individual’s mitochondria — inherited only from the mother — revealed that his mother was a narwhal and therefore his father must have been a beluga. This was a particularly surprising result because the tusk of the narwhal, its most distinguishing feature, has been hypothesized to be a secondary sexual characteristic for males. But despite the absence of a tusk, a male beluga was able to successfully mate with a female narwhal.

Precisely where this interspecies romance took place is not clear. Both belugas and narwhals are migratory, and we have fairly limited knowledge about where they go throughout the year. The skull was recovered in Disko Bay in West Greenland, which is one of the areas of the world where both species occur in fairly large numbers at the same time during their mating season (between late winter and late spring). It is plausible that the parents mated in Disko Bay.

Hybrid distinctions

Simply knowing that this hybrid existed is certainly intriguing, but we were also interested in how this unusual animal lived. In my lab at Trent University, I analyzed the stable isotope composition of the protein that was extracted from the skull of the hybrid as well as some belugas and narwhals from West Greenland. Isotopes are variants of the same chemical element that have different numbers of neutrons.

There are subtle variations in the distribution of these isotopes in the environment. Their relative abundance in our bodies reflects the kinds of foods that we have eaten, the places where we have lived and even some aspects of our health.

Our research team studied the stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen occurring within the protein collagen, which tell us about the average diet over the animal’s lifetime. These results showed a difference in the diet of narwhals and belugas, suggesting that each species had a distinct ecological niche.

We anticipated that the hybrid might have a diet that was intermediate between the two parent species, but in fact we observed a radically different isotope signature in the hybrid, suggesting that it had a very unique diet that was quite distinct from either belugas or narwhals.

Lifestyle variations

The hybrid had an unusually high carbon isotope value, which could signal that it obtained a much larger proportion of its prey from at or near the ocean bottom. Because our isotope data reflect the average diet over many years, we know that this individual must have had this unique diet for all of its life, possibly because his very unusual teeth forced him to specialize on consuming prey that were not typically eaten by belugas or narwhals.

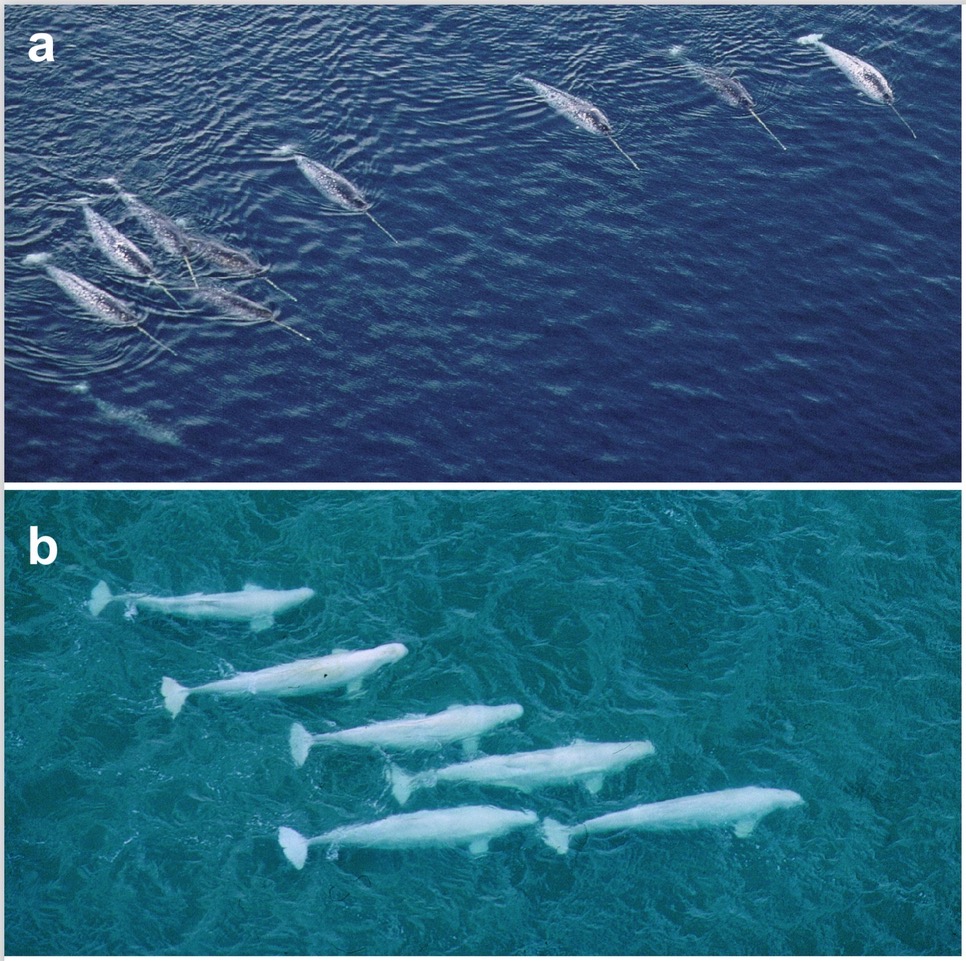

It is possible that hybridization between belugas and narwhals occurs with some regularity. The hunter that killed this individual observed several other unusual looking whales at the time: these appeared to have features — such as the shape of the fins — that were a mix of beluga and narwhal characteristics. Last year there was a widely reported story about a narwhal that integrated itself into a beluga pod in the St. Lawrence River.

[Read more:A narwhal frolics with the belugas: Why interspecies adoptions happen]

Our study showcases how we can use biomolecular techniques to mine new information from natural history collections, including specimens collected by museums over the last few hundred years, animal bones from archaeological sites and palaeontological specimens.

Paul Szpak is an assistant professor at Trent University in Ontario, Canada.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.