How Angry Birds and prospects of Chinese funding power visions of the shortest-ever route from China to Europe

ANALYSIS: A new Arctic rail link could position Finland as China's gateway to Europe.

I have just come back from Oulu, a major city in northern Finland, where temperatures dropped to minus 26 degrees Celsius (minus 15 Fahrenheit). Oulu may soon be an important stop on the shortest route between China and central Europe the world has ever seen.

That may not mean much to readers in North America, but in European terms we are talking a potentially major reconfiguration that resonates with the very current debate on China’s influence in the Arctic.

The fact that one of the key actors is also the inventor of Angry Birds, a Finnish mobile game gone global, only makes these developments the more stunning.

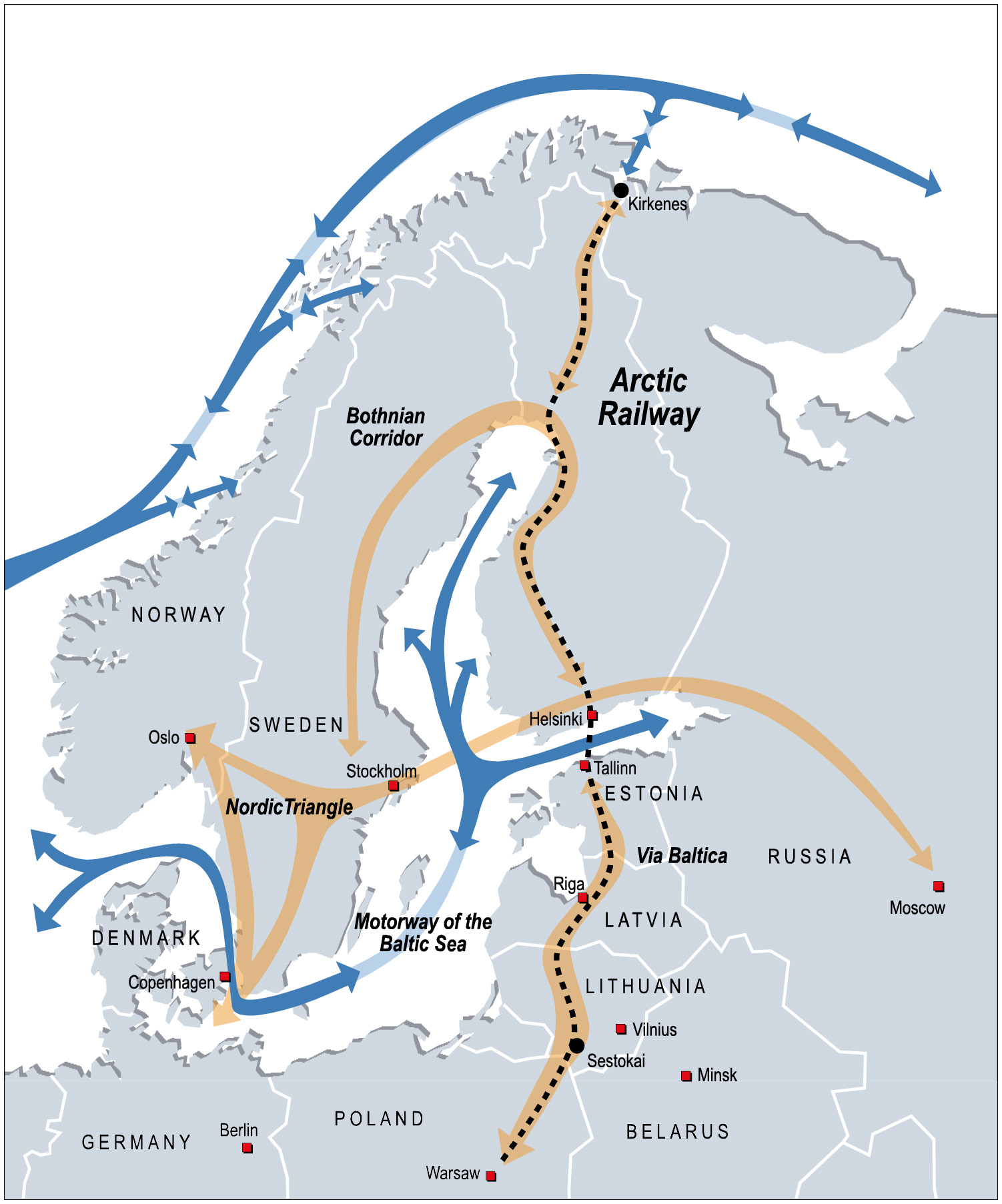

Spurred by climate change and hopes of funding from China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative, the governments of Norway and Finland are breathing new life into a vision of an Arctic Corridor from Asia to the European mainland.

If it happens, Chinese and other Asian ships will dock in northern Norway on the shores of the Arctic Ocean, shaving off thousand of nautical miles compared to the route through the Suez Canal. In Norway they will pick up goods and raw materials from Europe and load Asian goods on to trains through Finland, through a tunnel to Estonia and onwards to the heart of Europe.

Two missing links — some 500 kilometers (about 310 miles) of railway from The Arctic Ocean to Finland’s existing rail network and a tunnel from Finland to Estonia have put off planners so far — but climate change and prospects of Chinese funding have emboldened the enthusiasts behind these aspirations. As Risto Murto, Deputy Director-General in the Networks Department of the Finnish Ministry of Transport and Communications, told me, “When we think of the new corridors to China we are in the middle between Europe and Asia. Finland is not an island anymore. We look at our geopolitical position in a whole new way.”

The Ferris wheel

The scope of these China-connected ambitions is astonishing. Even from 40 meters above Helsinki’s harbor front, from the top of the local Ferris wheel, I could not see Tallinn or any other part of Estonia.

I went up in minus 15 Celsius, it was sunny and bright, but the Bay of Finland is 80 kilometers wide and, if ever built, the tunnel between Helsinki and Tallinn will be the world’s longest.

Every day more than 23,000 passengers travel between Helsinki and Tallinn. Finland’s own estimates say that the harbor in Helsinki serves more passengers than any other harbor in the world and the first plans for a more robust link to Estonia date back to the 1880’s. Finland’s government now regards a tunnel as a natural step into the future — even if the costs are expected to reach as high as a staggering 20 billion Euros.

[Finland and Estonia’s undersea rail tunnel could cost $20 billion by 2040]

Government backing

Finland’s Minister of Transport and Communication, Anne Berner, actively advocates the new Arctic Corridor — rail, tunnel and all.

On Mar. 1 she received a first feasibility study of the possible train link from Finland to the Arctic Ocean from the regional authorities in northern Norway and northern Finland. Then, on Mar. 9 she held a press conference, also featuring the former Finnish Prime Minister, Paavo Lipponen and, on video-link from Norway, the Norwegian Minister of Transport, Ketil Solvik-Olsen.

[Finland will pursue Rovaniemi-Kirkenes route for new Arctic railway link]

“The Arctic railway is an important European project that would create a closer link between the northern, Arctic Europe and continental Europe. The connection would improve the conditions for many industries in northern areas. A working group will now start to further examine the routing to Kirkenes,” Berner said, according to the Independent Barents Observer. The cost of the rail link from Kirkenes in Norway on the shores of the Arctic Ocean to the existing rail network in Finland is now estimated at 2.9 billion Euros.

As for the other missing link, the tunnel from Finland to Estonia on Europe’s mainland, Anne Berner and her Estonian colleague recently published an optimistic, EU-funded study of how to drill a tunnel from Helsinki to Tallinn, the capital of Estonia on the other side of the Bay of Finland. This study was presented in Tallinn by the two governments and in Brussels by Estonia’s former minister of foreign affairs, Urmas Paet, now a member of the European Parliament.

Finland already consider itself Europe’s air traffic gateway to China and Asia. Helsinki Airport is closer to China than any other in the EU at only seven and a half hours to Beijing. The number of passengers flying from Helsinki to China grew 16 percent from 2016 to 2017. The proposed Arctic Corridor will further link Finland to China, as will a proposed new high-speed broadband cable from Finland to Asia through the Arctic Ocean. Cinia, a Finnish IT-company 77.5 percent of which is owned by the Finnish state, heads efforts to establish the cable with Chinese and other foreign funding and the government in Helsinki actively promotes the project.

China and Mr. Angry Birds

The government in Helsinki has not officially dropped the thought of a partly EU-funded, government driven tunnel-building project, but this would likely drag on for years, and as Risto Murto from the Ministry of Transport and Communication tells me, “There will not be two competing tunnel projects.”

The government instead may be more inclined to leave further efforts to a private consortium that has vigorously pursued the tunnel for some time.

The consortium and its quest for Chinese funding is headed by Finnish entrepreneur Peter Vesterbacka, the wealthy inventor of Angry Birds, a colourful mobile game that has won millions of fans across the world. “I expect that Chinese investors will cover two-thirds, while northern European pension funds will probably cover most of the rest of the 15 billion Euro,” he told me in Helsinki. We met at his spartan office at We+, a share-space office complex run by Chinese investors popular with funky startups. Vesterbacka routinely appears in sweatshirts with Angry Bird motifs. He commutes to China, he says, at least twice a month and is busy learning Mandarin.

Vesterbacka’s company, Finest Bay Development, has formed a consortium with two Finnish construction companies, Poyry and Fira. Poyry is well known for its involvement with what is presently the world’s longest tunnel, the Gotthard Base Tunnel that runs for some 57 kilometers (about 35 miles) through the Swiss Alps.

I ask whether Vesterbacka expects the EU to be a main source of capital for the tunnel.

“No, definitely not,” he says. “We cannot wait for the rest of Europe to get their act together before we move on. We want to open the tunnel on 24th. December 2024.”

Vesterbacka would not name specific Chinese investors, but said talks were ongoing. “We are looking in particular at Chinese organizations already financing the Belt and Road Initiative. In Kazakhstan, new infrastructure to the tune of 50 billion U.S. dollars is being built as part of this initiative,” he said.

To replace the U.S.?

Some analysts claim, of course, that the China’s president Xi Jinping uses the Belt and Road Initiative to replace a world order dominated by the U.S. with a more sinocentric one. Others seem to view the project as a large and basically neutral investment in relevant infrastructure. Two weeks ago, the Finnish chairman of the Arctic Business Council, Tero Vauraste, embraced China’s Arctic engagement — and China’s interest in the proposed Arctic Corridor. Talking to Greenland’s main paper Sermitsiaq he was quite clear: “We should not regard China as an enemy but as an investor like all others,” he said.

“China is an important player in the Arctic region. We will see China involved in many more projects and connections in the future. That is inevitable — and much needed,” he said (my translation).

In Helsinki, Peter Vesterbacka agreed: “The world’s focus towards Asia is happening very rapidly. That is where growth and all the people are now, and Finland is perfectly positioned to take part in it,” he said.

He did not worry that China would misuse its influence with the tunnel to Tallin, a potentially crucial piece of infrastructure, towards political ends: “No, why would they? Listen, we start-up people are probably just not that worried that the world will stop soon. And if it does I guess we’ll have to find a way to deal with,” he said.

Critics claim that Finland’s decision-makers have become less willing to criticize China. In 2017, when seven EU countries, among them Sweden and Estonia, two of Finland’s neighbours, raised concern over China’s repression of human rights lawyers, Finland remained mum — and visiting China in 2015, the Speaker of the Finnish parliament refused to take up human rights issues.

Pandas in Finland

Of the proposed new infrastructure to link Europe and China through Finland, the railway leading from existing railways in Finland to the Arctic Ocean are considered the least likely to materialize any time soon. Murto of the Ministry of Transport and Communication said construction was likely to begin in 2030 at the earliest, and that progress was dependent on, among other factors, unpredictable growth in international traffic on the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s northern coastlines.

Politically, however, the Arctic Corridor seems likely to remain in focus. China is already Finland’s second largest trading partner outside the EU after Russia. In May 2017, President Xi Jinping made a two-day stop in Finland, his only stop-over on his way to talks with U.S. President Donald Trump in Florida in the US. Two Chinese pandas on loan from China were recently released in Helsinki’s zoo as part of China’s “panda-diplomacy”, several thousand Chinese students make China a major source of new talent, and the Chinese New Year is celebrated in Helsinki every year.

Local interest

In Finland’s Arctic, interest in the new connection to Asia is particularly obvious. In Oulu temperatures had dropped to minus 26 Celsius — cold even in these parts — but enthusiasm for the Arctic Corridor remained vibrant. Pauliina Pikkujamsa, head of marketing of BusinessOulu, a northern Finland business association, told me how “this would certainly be interesting from our perspective. It would bring large amounts of traffic our way and provide new export avenues for us to China. It would provide Finland with a whole new role between Asia and Europe.”

Northern Finland is home to great herds of reindeer and touristy imitations of Santa Claus, but it is also in this region that some 2,000 engineers work at one of Nokia’s high-tech innovation centers, and the world’s first test-site for automated, unmanned ships has recently opened on the Bay of Bothnia. China’s import of Finnish technology and paper goes back a long time. China’s Sunshine Kaidi New Energy Group wants to invest big in the production of biofuels here, other Chinese investors are already part of a northern Finland tourism boom and the mines in the region contain several minerals bound to attract China’s attention: gold, copper, uranium, lithium, zinc and nickel.

As plans unfold, several obstacles are likely to occur. The Sami communities in Northern Finland will probably not be pleased by a set of rails cutting through reindeer forest; concerns over the marine environment are bound to materialize further south as the massive tunnel-project becomes better known in Finland.

But for now the enthusiasts seem to be holding the controls.