The Arctic Cycle connects climate change, art

New York-based playwright Chantal Bilodeau has embarked on an ambitious effort to write eight plays about the Arctic — one for each Arctic nation.

“We must correct the global imbalances caused by the great disconnections that have grown between us.”

This quote, attributed to Inuit climate change activist Shelia Watt-Cloutier, proceeds “Sila,” a play written by Chantal Bilodeau. It’s also the ethos of Bilodeau’s The Arctic Cycle, an organization with a goal to provoke conversations around climate change and the Arctic with art.

Bilodeau was inspired to start her ambitious project—which will involve writing eight plays, one for each of the Arctic states—after trips to Alaska and Canada, where she saw retreating glaciers and the impacts of a warming climate.

“The combination of climate change being more present in the mainstream media and me seeing it firsthand, made me think that even though it was a personal interest of mine, maybe I can incorporate this in my work,” Bilodeau said.

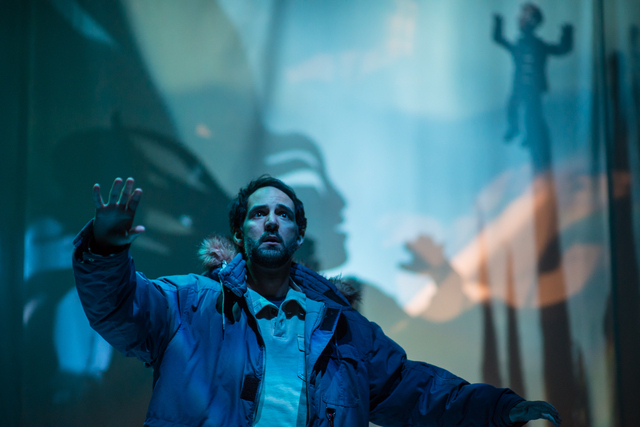

The first play by Bilodeau’s Arctic Cycle, “Sila,” is set on Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. The play tracks the seven characters’ interactions and interconnectedness around the Arctic land, including a climate scientist, Inuit activist, Coast Guard officers and a polar bear. As the climate scientist Jean rushes to witness a rare environmental event without a full understanding of the landscape, Leanna and her daughter Veronica rouse up climate change activism on the political and grassroots levels.

Scattered throughout are discussions around oil rights, sovereignty and economic development, and how these issues are interconnected.

“I can write a play about environmentalists and I could write one about ‘bad oil’ but it’s not helping,” Bilodeau said. “I think what’s helping is understanding how all of the elements are coming together, and as soon as you move one you move everybody else.”

Anchoring the scenes are tender moments between a mother polar bear and her cub, brought to life with the help of large puppets on stage. Bilodeau also weaves in spoken word poetry from Taqralik Partridge, an Inuit throatsinger and writer from Kuujjuaq, Nunavik.

Her second play, “Forward,” focuses on Norway. Rather than looking at the interactions people have with each other physically, Bilodeau illustrates how humans can be connected over time.

Beginning in 1893, the play ricochets through hundreds of years, first focusing on the Norwegian Arctic explorer Fridtjof Nansen and then bouncing from his plans to reach the North Pole, the 1969 discovery of oil in the North Sea and conversations between an oil company employee and his wife. With climate change affecting many of the characters, it helps illustrate how one action years ago may influence the present or future.

“You see how small decisions we make in day to day life, where we think that we are doing our best, have bigger consequences down the road,” Bilodeau said.

Bilodeau took multiple years to write both “Sila” and “Forward,” which premiered in 2014 and 2016, respectively. The process of writing included traveling extensively in the Canadian Arctic and Norway, interacting with community leaders, activists, politicians and scientists that work and live in the regions.

After returning to her home base in New York City, she then goes through a process of “digesting” all the information she acquired, writing multiple drafts and then working to find funding to produce the plays. “Sila” was produced and shown the University of New Hampshire, MIT in Cambridge and Cyrano’s Theatre Company in Anchorage. Readings and workshops were also conducted across Canada and the United States.

Now, Bilodeau is in the process of writing her third play “Untitled,” set in Alaska. For her research, Bilodeau first hiked into the Alaska Interior, then, through the Tidelines Ferry Tour, visited nine communities in southeast Alaska with a group of artists. In some of the indigenous communities they visited, the artists gave a short presentation and hosted a conversation asking residents what kinds of changes they were witnessing. Bilodeau read an excerpt from “Sila.”

While “Sila” and “Forward” were performed primarily in the lower 48 U.S. states, Bilodeau hopes that her one-woman Alaska play will make it easier to travel to some of the locations she visited during her research phase.

“I wanted to bring the play back to those communities and that was one of the thoughts about the one-woman play,” Bilodeau said. “I could show up without anything, just one person; I don’t need lights, sets or costumes.”

The Arctic Cycle has also expanded beyond Bilodeau’s plays, supporting other initiatives that explore the challenges of climate change through art. Climate Change Theatre Action leads a series of readings and performances during the United Nation’s Conference of Parties, and the Artists and Climate Change blog provides a resource for artists interested in incorporating the themes of climate change in their work.

Through all these efforts, Bilodeau’s mission remains the same: to illustrate the link between the viewer, the characters and the vast Arctic.

“It’s about trying to make the Arctic a little more vivid in people’s imagination and understand what we do here impacts people there,” Bilodeau said.