Arctic fisheries brace for ‘significant’ effects from China’s coronavirus lockdown

As dozens of Chinese cities remain quarantined and commerce has slowed, it’s unclear what the global repercussions on trade will be.

While China battles a rapidly spreading new coronavirus, now known as COVID-19, it’s also facing an economic slowdown as many businesses remain closed or at limited capacity.

The economic ripple effects are being felt as far away as Nunavut. Those in the Arctic fisheries industry are watching the developments closely to see whether seafood markets will tumble — or perhaps rise.

The Lunar New Year is usually a time of celebration, with millions of participants attending massive festivals. And Arctic seafood is often on the menu.

“China is our biggest market,” Mark Quinlan, president and CEO of Newfound Resources, which sells Canadian coldwater shrimp to international markets, told ArcticToday. “And business really depends on consumption during Chinese New Year.”

But when the coronavirus began spreading across China, authorities quickly instituted travel bans and lockdowns for millions of people. Many Spring Festival celebrations were canceled, and the new year was ushered in quietly, often in the privacy of homes.

The virus has also been reported in 25 other countries, but most of the cases have been in China, where more than 1,300 people have died.

Chinese businesses and banks have been closed for two weeks, and the markets that do open are heavily restricted, Quinlan said, in terms of how many people are allowed in and how many trucks are permitted to distribute food.

The country’s seafood consumption may have dropped by as much as two-thirds, industry analysts say.

Fisheries in the Canadian North have risen steadily over the past decade. The Nunavut Fisheries Association, which represents four fishery operators across Nunavut, estimates that fisheries have an economic impact of $112 million on GDP. In 2011, turbot alone had a “landed value” of about $70 million in Nunavut.

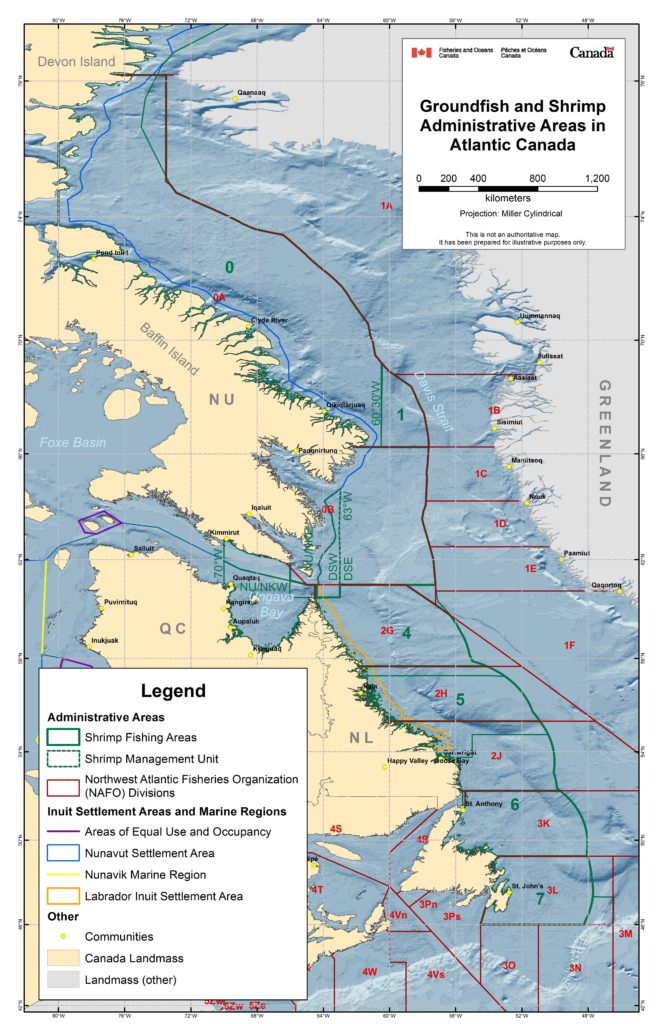

Northern Canadian fisheries supply Chinese markets with frozen turbot, shrimp, and Arctic cod. They work in the eastern Davis Strait, between Baffin Island and Greenland, ranging as far north as Devon Island all the way down to Newfoundland and Labrador.

Because Nunavut produces frozen seafood, they delivered much of their product in December, in preparation for the new year.

Yet much is unknown about sales since then.

“I know what we’ve sold, but I don’t know what the consumption in the market has [been],” Quinlan said. His company works primarily with distributors, and it’s unclear how much product those distributors have in turn sold at grocery stores and local markets, and how much was consumed during New Year celebrations.

Quinlan’s company usually ships to China every three to four weeks. Their next shipment is due to arrive in two weeks — but he still doesn’t know yet whether banks will be processing international wire transfers and whether cold storage facilities will be reopened.

Marius Linstead, general manager of Sirena Canada Inc, which helps market North Atlantic seafood globally, told ArcticToday that the China market is basically shut down.

“People aren’t working; they’ve been told to stay home,” he said. One of their clients has seafood stored there, and customers in China have asked to buy it, but they can’t access the product because the cold storage facilities are closed, he said.

Brian Burke, executive director of the Nunavut Fisheries Association, told ArcticToday that the virus has “huge” implications on the seafood trade with China, particularly because the Arctic seafood industry has been heavily dependent on China.

“The whole global economy has been so dependent on China,” Burke said. For the past couple of years, Chinese trade “has really been the engine that’s kind of kept things going” — not only with sales, but also longer-term investments in infrastructure like ports.

For now, seafood from Nunavut is being stored in Canada, awaiting shipment either to China or to other markets in Europe, North America, or elsewhere in Asia.

“But taking out that much of the market, it’s not going to be easy to find places,” Burke said. “It wouldn’t surprise me to see some declines in the price — some significant declines in prices.”

The big question, he said, is how long this slowdown will last.

Linstead agreed. “I can’t wrap my head around the timeline ’til they bounce back,” he said. “Is this is going to be another month, or is it going to be a year? I have no idea.”

Elsewhere in the Arctic, Greenlandic fisheries are also waiting to see how the lockdown will affect their seafood exports. Russia is diverting live crab shipments away from China and into other countries in Asia, as prices for live seafood drop. And Iceland, which added seafood to its existing trade agreement with China last May, saw a promising open to the season wither under difficult weather conditions and coronavirus restrictions.

China is also the biggest customer of Alaska fisheries. Alaska is expected to see declines in its fishing industry as well as oil, tourism and shipping due to the lockdown.

Hannah Lindoff, senior director of global marketing and strategy at the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute, told ArcticToday that China is a “tremendously important player” in the global seafood industry.

“Prior to the trade dispute, China was the number one export market for Alaska seafood,” she said, both for consumption and reprocessing of seafood. “China remains critical to Alaska seafood now and for the future,” she said.

On Tuesday, Jerome H. Powell, chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve, told Congress they are “closely monitoring the emergence of the coronavirus, which could lead to disruptions in China that spill over to the rest of the global economy.” Some have predicted that the economic effects of the new virus could be worse than SARS, which cost an estimated $50 billion.

On the same day, the Chinese government urged countries that had restricted travel to “restore normal ties for the sake of the global economy,” according to reports.

Linstead is concerned about repercussions from some countries’ overly harsh travel restrictions, which he called a form of discrimination. There was a bigger outbreak of the H1N1 swine flu in the United States in 2009, he pointed out, but other countries didn’t shut down travel like this.

“China could continue to get pissed off, for lack of a better word, with the way they’re being treated,” he said.

Quinlan said there is plenty of fear and concern in the Northern seafood industry right now, but they don’t know what the long-term effects will be.

“There’s a concern that, you know, businesses shut down and things are going to be very bleak. And for some industries, it may be,” Quinlan said. “We’re just hopeful that in the next week or two we’ll have a better idea of where things are going to go.”

But, he said, changing patterns of food consumption in China could actually result in a long-term rise in seafood demand. The Chinese government temporarily banned the wildlife trade over concerns that the coronavirus may have originated in wild meat. Since then, Quinlan said, officials have promoted eating seafood instead.

“That kind of government promotion might mean an increase in our business,” he said. But it’s too soon to tell if consumption is changing in any meaningful way.

“We’re just cautiously optimistic that things will slowly get back to normal,” Quinlan said. “And we’re hopeful that that the demand remains the same.”

Keith Coady, the general manager of Qikiqtaaluq Fisheries, based in Iqaluit, told ArcticToday that the fishermen he works with are apprehensive, but waiting to see what will happen. Coady himself is cautiously optimistic.

“I think it’s going to be okay. We went to through SARS before and everything else, so I think this might pass,” he said. “But who knows?”