Arctic leaders gathered in Anchorage ponder a path forward without Russia

“Now we have to proceed without them.”

At a two-day Arctic conference in Anchorage last week that was packed with dignitaries and experts from around the Arctic, the talk was dominated by who was not there.

There were no representatives of Russia, the nation with about half of the Arctic’s landmass and coastline, at the Arctic Encounter Symposium.

At this event, as with other international events, Russian government participation was excluded, a response to that country’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russia’s status as a pariah is well-deserved, said diplomats and political leaders from the other Arctic nations: Norway, Sweden, Finland, Iceland, Greenland, Canada and the United States.

“We’ve seen atrocities brutalities, against Ukrainian civilians and a violation of principles that are extremely important to the Arctic,” Jim DeHart, the U.S. State Department’s coordinator for the Arctic region, said at a Friday news conference.

“The Russia we see today is an aggressive, violent war machine,” said Anniken Ramberg Krutnes, Norway’s ambassador to the U.S., said in a panel discussion Friday evening.

Russia’s war prompted the other seven Arctic nations to pause their participation in the work of the eight-nation Arctic Council, which emphasizes cooperation and consensus. Russia is currently chairing the forum, serving its two-year rotation in that role.

The invasion has also been a rude awakening for council participants, which had long viewed that forum as a place for constructive cooperation with Russia outside of any other geopolitical problems, Krutnes said.

“We have to admit that that’s over now,” she said. “Now we have to proceed without them.”

But just how to proceed remains to be determined, officials said.

There are worries about a rogue Russia causing damage even as the rest of the Arctic nations try to work together to address challenges like climate change.

Those worries extend to an upcoming international meeting that will launch a research program as mandated by a 2017 agreement — to which Russia is a key signatory among the 10 governments — that indefinitely closes the international waters of the Arctic Ocean to commercial fishing. The meeting, postponed by the COVID-19 pandemic, is now scheduled for November in South Korea, said David Balton, a longtime U.S. diplomat who helped negotiate the fishing ban.

“Will it happen with Russia? I don’t know. Can it happen without Russia? I don’t know,” Balton said.

Now serving as executive director of the White House’s Arctic Executive Steering Committee, Balton spent much of his career promoting mutual interests and cooperation in the Arctic. He admitted at the Arctic Encounter Symposium that he has found his longstanding optimism about the region dashed.

“My view of the Arctic changed on Feb. 24,” he said, naming the date of Russia’s Ukraine invasion. What made the Arctic “special” and “extraordinary” has been violated, he said, and it appears “we’ve reached some kind of an inflection point.”

Isolating Russia through sanctions and boycotts, though necessary, can be painful, the Arctic leaders said.

That will be the case for Greenland, said Kenneth Høegh, who heads Greenland’s representation in Washington. Last year, Russia accounted for 14.6 percent of Greenland’s exports, so sanctions will hurt the economy, Høegh said. “That is something that we’re going to feel quite hard,” he said.

But the officials said they are determined to stand against Russia.

“What is happening is instead of dividing us, Putin is unifying us in Europe,” said Tiina Jortikka-Laitinen, Finland’s ambassador for Arctic issues.

For the first time in history, she noted, a majority of Finns now support NATO membership. The national government is working on a report examining membership and will be considering options, she said.

But there were also arguments at the symposium for some exceptions to the total isolation of Russia.

One example came from the Inuit Circumpolar Council. For the ICC, which represents Inuit peoples from Greenland to northeastern Siberia, it is important to stay engaged with those constituents inside Russia’s borders — even though working with Russia’s national government is now “unthinkable,” said Dalee Sambo Dorough, the ICC’s international chair.

“I think we’ve illustrated as Indigenous peoples the opportunity to transcend borders and communicate in order to achieve our shared interests,” Dorough said during a Friday panel discussion. The current uncertainty is difficult, she said. “Nevertheless, we still extend our hand across such borders. . . . I think there are ways and means to allow that to happen, certainly with the seven of eight.”

Another example is the continued relationship with the Russian Border Guard to cooperate on emergency responses in the Bering Sea.

There are also efforts ongoing to preserve the personal and research relationships with Russian scientists — even though any relationship with the Russian government is off the table. Officials said they hope that the links between scientists will not be permanently severed.

“There are, no doubt, some Russian scientists that are doing good work and hopefully will continue to do work, wherever they are, and to share their data when the time is better to do so,” DeHart said.

With or without Russia, there are critical needs in the Arctic that must be addressed, starting with rapid climate change, the officials said.

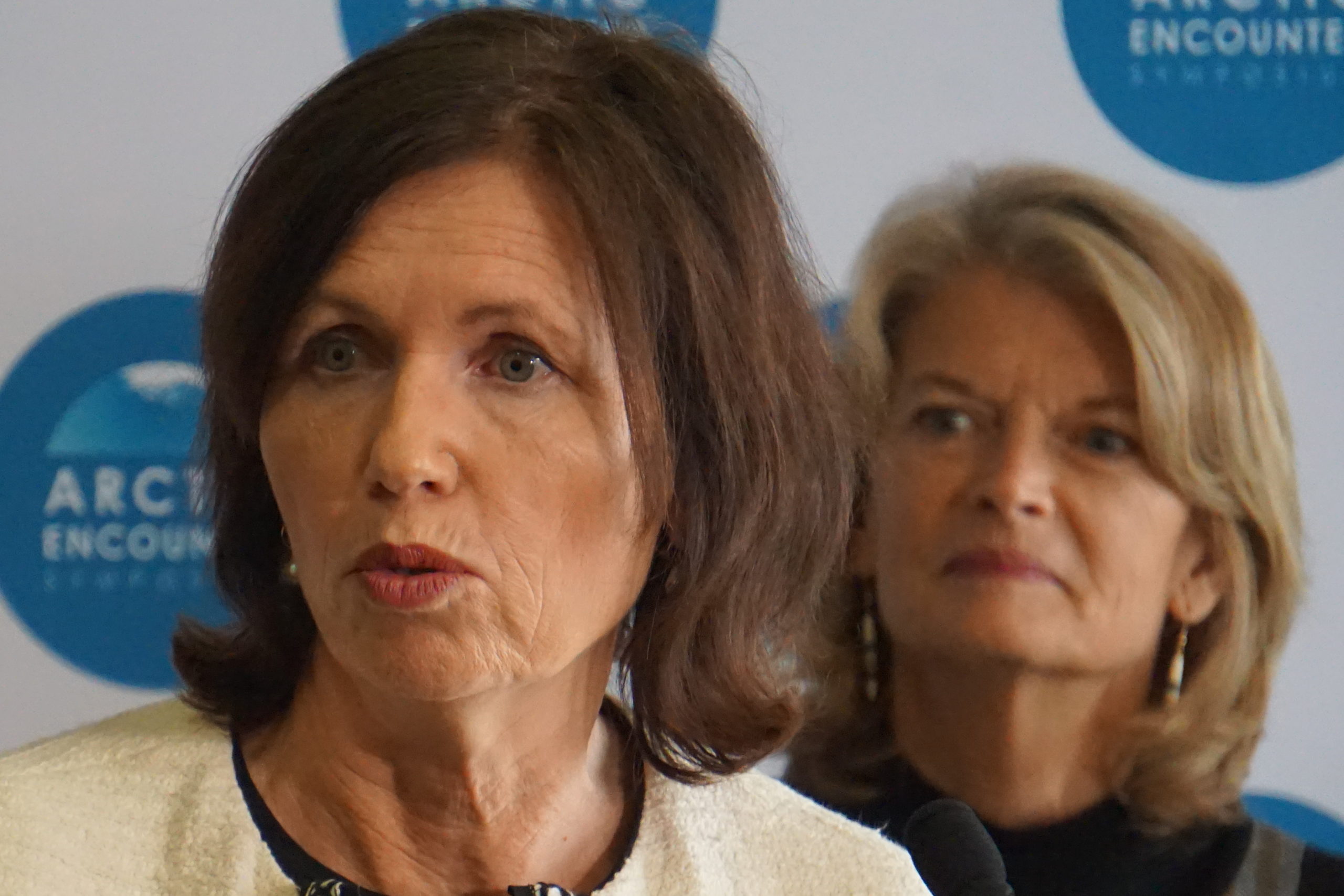

“The Arctic itself cannot be put on pause,” said Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski. “We have got to figure out how we can continue our efforts to work as Arctic nations together.”