Threat to oil becomes real as climate crashes Norway’s election

Politicians and activists who have been fighting to rein in Norway’s mighty oil industry are eyeing a breakthrough.

Several parties opposed to further oil exploration could emerge as kingmakers in the Sept. 11 election. That will threaten a push to search for about 9 billion barrels in Arctic crude and natural gas, which is necessary to prolong the petroleum age that made Norway one of the world’s richest countries.

[Future of oil takes center stage in Norwegian election]

“I’m very worried,” said Stale Kyllingstad, chief executive officer of IKM Gruppen, one of the biggest suppliers to the oil industry.

Big oil’s enemies are now gaining ground with both moral and financial arguments. Norwegians are increasingly questioning how to reconcile their role as western Europe’s biggest oil and gas producer with fighting climate change and whether searching for more petroleum is the financially sound thing to do in a world where renewable energy is taking over more and more.

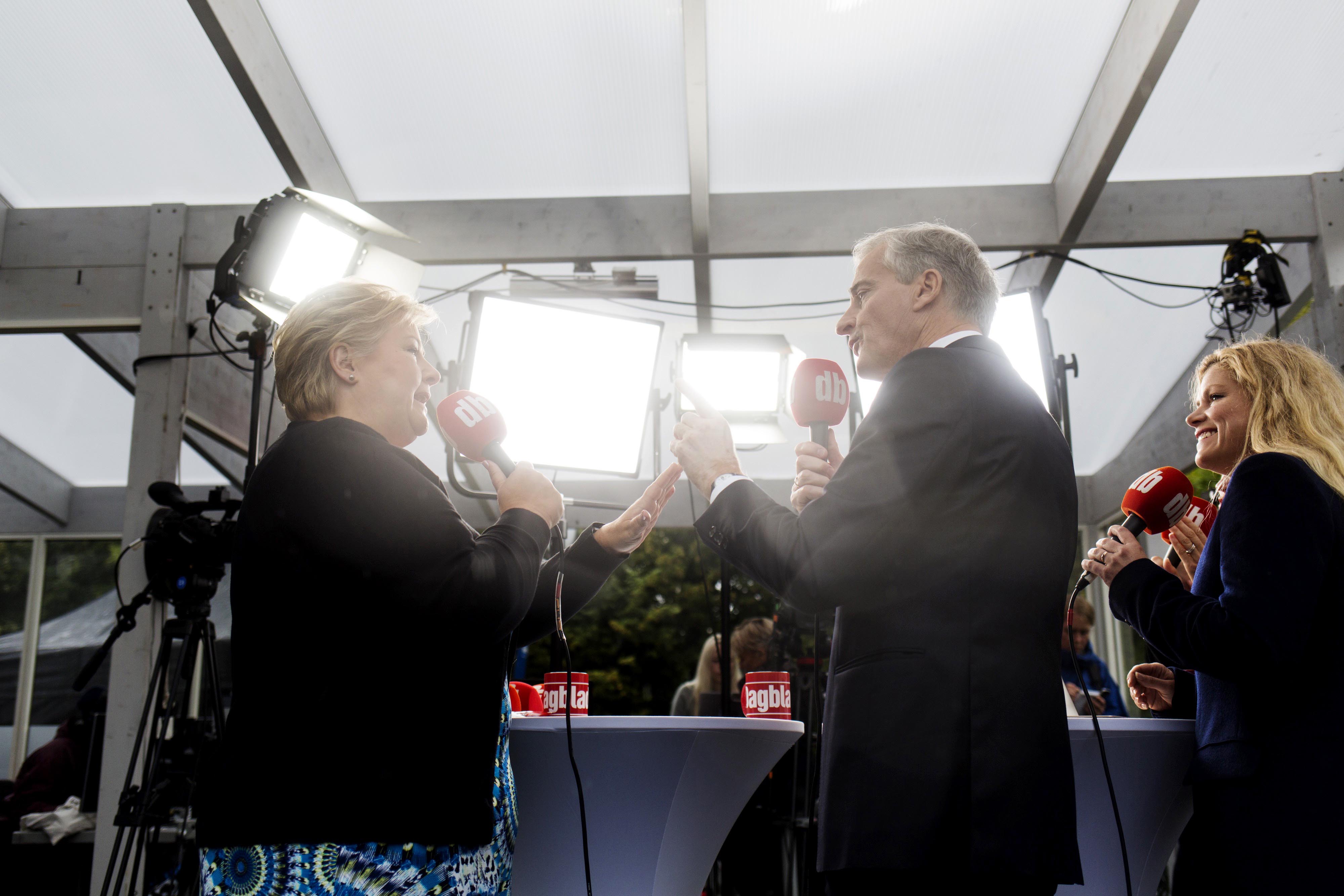

The Green Party, which wants to end exploration immediately and phase out the industry in 15 years, is poised to become a key parliamentary force. The race is too close to call between Conservative Prime Minister Erna Solberg’s government and the opposition, headed by Labor leader Jonas Gahr Store. Polls suggest both blocs could fail to win a majority.

[Norway’s anti-oil Green Party could hold key to election outcome: DN poll]

Labor, a historic supporter of the oil industry, has seen its backing plunge in recent weeks, making it dependent on support from smaller parties seeking to curtail drilling. A key Labor politician last month even suggested reviewing tax subsidies for exploration, shocking the industry before the party clarified that it wasn’t about to change a system prized by oil companies for its stability.

That failed to reassure Kyllingstad, who said he feared a weak Labor Party would be forced to “prostitute itself” to “extremist parties.”

The Socialist Left (Labor’s government partner until 2013) and the Red Party, which both want to end license awards and new field developments, also stand to gain.

To be sure, Labor and the current government parties, the Conservatives and the Progress Party, all industry backers, are likely to remain the three biggest groups after the election, sharing well over half the votes.

But the smaller parties, which for now have had little more to celebrate than a ban on drilling off the Lofoten islands, could extract deeper concessions, said Anders Holte, an analyst at Danske Bank in Oslo. That could include fewer license awards and possibly jeopardize a program that lets loss-making companies collect 78 percent of exploration expenses in cash, he said.

For an industry that lost 50,000 jobs during the oil crash, it would be a bad blow. It could especially threaten an expansion in the Arctic Barents Sea, which holds the bulk of the country’s undiscovered oil and gas resources and is seen as key to maintaining production 10 years from now after it already dropped by 12 percent since a 2004 peak.

“For the first time in a long while, there’s increasing political risk,” Holte said.

The outgoing government has pushed hard to stimulate exploration in the Arctic, overseeing a record search for oil in the Barents Sea, including Norway’s northernmost well, and offering the most blocks ever in that region in a licensing round. On Wednesday, the Petroleum Ministry said it received a record amount of application in a round focusing on mature blocks after Barents acreage had been boosted.

Rasmus Hansson, the only Green lawmaker for now, said the top priority is to end exploration for new oil. That’s a moral obligation because of climate change and a financial imperative because spending on exploration could be throwing money into the sea if the resources are never used as the world moves beyond fossil fuels, he said.

“It’s particularly naïve to believe that the oil industry will be profitable for a long time to come,” he said in an interview last week. “An increasing number of Norwegians are saying in polls that they see a future after oil.”

One survey showed last month that 44 percent of Norwegians would be willing to leave some oil in the ground if it helped cut emissions.

At Statoil, Norway’s biggest oil company, outward appearances are cool for now.

“I’m registering that there’s a greater diversity and a bigger stretch in the views on the Norwegian oil and gas industry,” Eldar Saetre, the company’s CEO, said in a phone interview this week.

Saetre said he wasn’t worried about a change in the fundamental framework conditions for oil companies. The powerful Norwegian Oil and Gas Association and the country’s biggest oil union, Industry Energy, also said they trusted the big parties to safeguard the industry because of its importance for jobs, value creation and government income.

But the industry could be overplaying its hand and Solberg has vowed to help the country wean itself off oil. Its dominance is slowly fading, and production now comprises about 12 percent of the economy, down from more than 20 percent pre-oil crisis. To be sure, that doesn’t factor in how oil cash seeps through other sectors of the economy.

“I understand that people in the oil industry are worried,” said Frode Alfheim, who represents thousands oil workers as head of the union. “I’m pretty certain that once one or the other constellation starts running the country after the election, the broad lines will remain firm.”