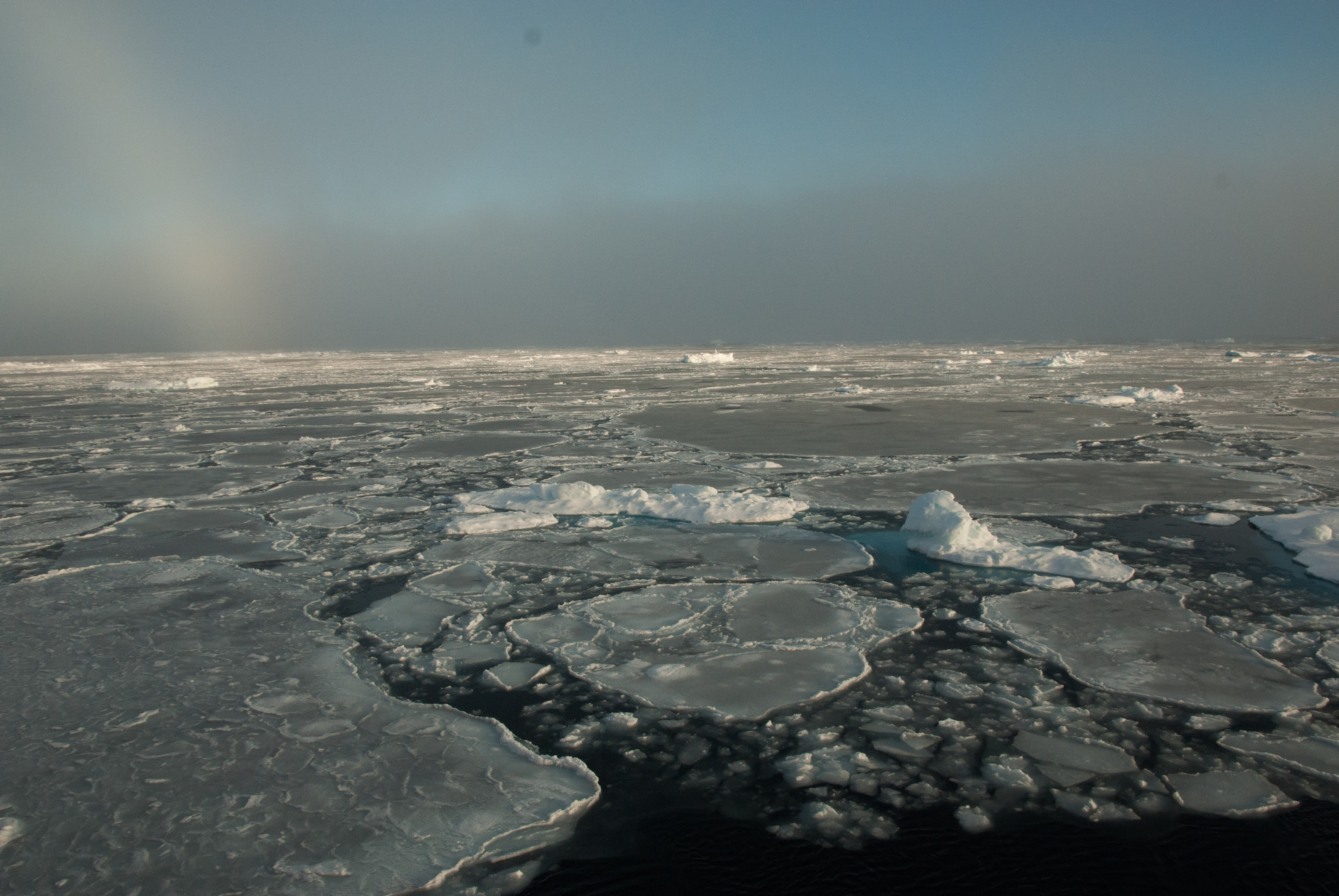

Arctic Ocean on track to be ice-free in summer by 2040

(Alek Petty / NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)

The Arctic Ocean is on track to become ice-free in summers as soon as two decades from now, while autumn and winter temperatures in the Arctic, if carbon emissions are not controlled, will be about 22 degrees higher in 2100 than they were at the end of the 20th century.

The new forecasts of accelerated warming mark the condition of the Arctic at the end of the two-year U.S. chairmanship of the eight-nation Arctic Council, according to reports released by the organization’s Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program.

Scientists are warning the pace of climate change demands a quick response against its causes.

The reports come two weeks ahead of the council’s ministerial meeting in Fairbanks, an event that will cap U.S.’ two-year tenure and pass leadership to Finland. The reports were released at a four-day Arctic science conference in Reston, Virginia, and outlined in a pair of teleconferences held Tuesday.

With Arctic warming outpacing climate change in the rest of the world, the reports show why immediate action is needed to reduce global carbon emissions, said one of the scientists involved.

“The changes are cumulative, and so what we do in the next five years is really important on slowing down the changes that will happen in the next 30 or 40 years,” said Jim Overland, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration oceanographer and a co-author of the Snow, Water, Ice and Permafrost in the Arctic report, or SWIPA. “The emphasis on action and immediacy is one of the key findings” of the report, he said.

The new SWIPA report shows major Arctic trends documented in past years have accelerated.

Since the last SWIPA report in 2011, the Arctic has heated up to its highest temperatures ever measured by weather instruments. Arctic sea ice hit a record-low extent in 2012 and last year tied for the second-lowest level in the satellite record, according to the new report.

Greenland, the Arctic’s biggest contributor to global sea-level rise, in 2011 to 2014, lost ice at twice the rate observed from 2003 to 2008, the report said.

The “big picture” described in 2011 is now more certain, as are projections for the future, said Martin Forsius, chairman of the monitoring and assessment program and research professor at the Finnish Environmental Institute.

“The difference is the confidence in the results is much greater,” Forsius said at one of the teleconferences.

Dramatic warming and Arctic ice losses in recent years are behind the SWIPA projections for an ice-free Arctic Ocean by the late 2030s — an earlier date than is suggested by most models.

Predictions about when that milestone will arrive vary widely, from the 2060s to just a few years from now, Overland said. The new SWIPA report uses extrapolation of recent observations to come up with an estimate, he said.

“It’s hard to pin down,” he said. “But this last summer, the ice was particularly thin and diffuse. So it’s not just the extent. The ice is changing within the pack.”

Also new since 2011 is emerging information about how amplified Arctic warming affects the rest of the world. There is new information about far-north warming causing the jet stream to slow, meander and exacerbate midlatitude weather problems, the SWIPA report says.

Rising sea levels, of which a third is now attributed to melt of Arctic land ice, is already causing flooding, erosion and property damage in southern cities, the report says.

Another challenge is posed by newly discovered contaminants, many related to flame retardants, in Arctic air and water, according to a separate AMAP report on chemical pollution.

Chemical contaminants, many of them from pesticides and industrial products used in faraway southern latitudes, have plagued the far-north marine environment for decades.

There has been significant progress in controlling those legacy contaminants, known as persistent organic pollutants, thanks to an international treaty — the Stockholm Convention — and national-level controls, according to past Arctic Council monitoring.

But the new contaminants are adding to the legacy load, and some, like pharmaceuticals, have local sources, the report said.

[The Arctic Ocean has become a garbage trap for billions of pieces of plastic]

Microplastics, newly documented in Arctic waters, are posing growing problems. The tiny plastic bits, broken down pieces of voluminous trash dumped into the seas far to the south, provide a way for contaminants to get into the Arctic food chain, according to the report.

Chemicals like phthalates, a possible toxin, adhere to plastic and are absorbed by it, so fish, birds and other creatures that mistake microplastics for plankton and other food are ingesting the contaminants.

Other reports released and discussed Tuesday concern human health, local strategies for adapting to change, economic development, marine environment preservation and oil-spill preparedness.

Among them is a strategy for addressing invasive species, to be presented at the council ministerial meeting.

“We found that the trend of invasive and alien species is particularly urgent for the Arctic region,” said Reidar Hindrum of Norway, chair of the council’s Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna working group.

Climate change accounts for the urgency, Hindrum said at the teleconference. “It’s opened the Arctic to species from both sides,” he said.