Arctic refuge snow conditions are even worse for tundra travel than previously reported

A new report found that two-thirds of the refuge had no snow or not enough to travel on.

If energy companies bring drilling rigs and other industrial equipment to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s coastal plain, it will be difficult for them to avoid harming the tundra as they search for oil, new research from University of Alaska Fairbanks shows.

Two-thirds of the coastal plain, a 1.5 million-acre area newly opened to oil leasing, had inadequate snow cover last winter to support heavy vehicles like those used for development, according to a new report from the UAF experts.

The report, a follow-up to earlier studies of tundra-travel conditions, found that snow cover earlier this year was far below the threshold at which vehicle movement is allowed.

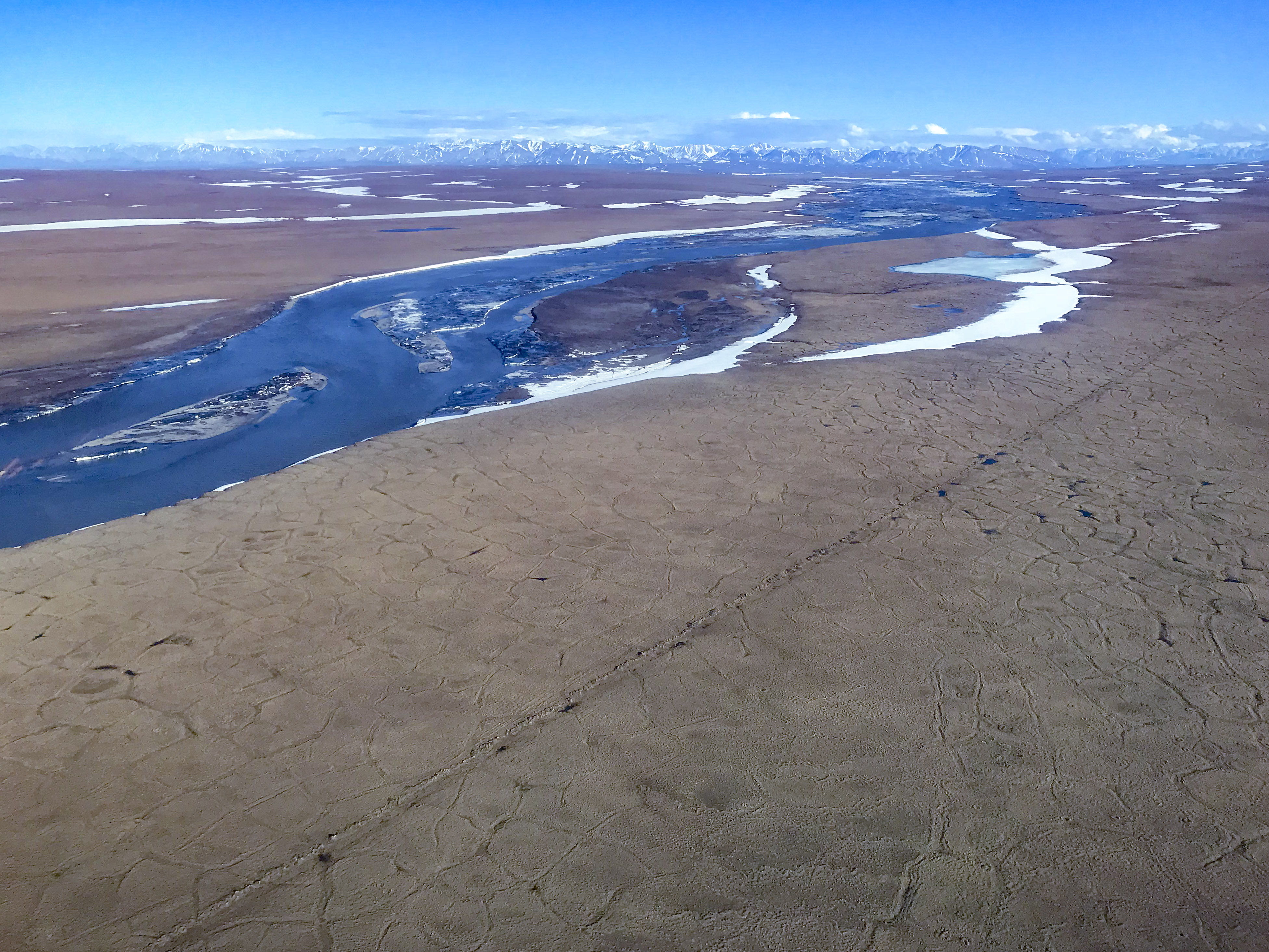

The UAF group traveled to the coastal plain last April, the end of the North Slope winter, a time when snow cover is at its maximum. It is also, generally, the time of year when tundra travel is most common. To assess conditions, they collected information through a combination of methods, including snow-pit measurements, snow water-content measurements and aerial mapping.

It was clear to those on site that snow cover was patchy and thin in spots, said Matthew Sturm, a snow expert with UAF’s Geophysical Institute and leader of the team that produced the study. “It was hard to move around on snowmobiles, and there were big bare spots,” Sturm said.

But the full severity of the situation was not evident until mapping showed that 67 percent of the tundra surface had either no snow or a layer of snow that was too thin to allow travel, he said. That was not readily apparent from visual observations, he said. “You can have two inches of snow, and it still looks white,” he said. “The perspective on the ground doesn’t tell you very much.”

On-site work in the previous winter found that about a quarter of the coastal plain lacked sufficient snow cover to permit industrial tundra travel. However, that winter had extremely heavy snowfall, while the winter of 2018-19 was a more typical snow year, the new report said.

Travel by industrial vehicles is allowed on the North Slope only when top layers of the ground are hard-frozen and when they are covered by sufficient snow to protect the tundra from damage caused by compaction.

Those conditions are rare on ANWR’s coastal plain, research by Sturm and his colleagues has shown. High winds funneled by the mountains that loom close to the refuge’s coastline regularly scour the winter landscape, removing snow in some places and piling up drifts in others. The sloped nature of the terrain, which is cut sharply by creeks flowing out of the mountains, also affects the quality of snow coverage.

The refuge’s snow conditions and other features affecting tundra travel were examined at a fall workshop conducted by UAF and by state and federal agencies. That workshop produced a report concluding that the ANWR coastal plain, from the standpoint of tundra travel, is more similar to the Brooks Range foothills than it is to other coastal regions of the North Slope.

In the area that hold the Prudhoe Bay and Kuparuk oil fields and in the coastal areas farther to the west, in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, tundra terrain is flat and even, the snow cover is more consistent. There, vehicle travel across the tundra has been is common — albeit on a seasonal schedule that has become shorter as the Arctic winters become warmer.

But in the Brooks Range foothills, where terrain is sloping and where creeks can cut deep into the landscape, adequate snow cover is more difficult to find. In the winter of 2018-19, none of the foothills region was opened to tundra travel because the snow conditions never reached the required threshold.

If companies do try to explore the ANWR coastal plain, a site also called the “1002 Area” after its legal designation, they will likely have to travel across it in different ways than are used on the rest of the coastal North Slope, the new report advises. Patterns of snowfall and snow accumulation are so different in the refuge “that using the same methods for snow roads and other overland travel will not achieve the same degree of protection as has been possible in those other areas. We strongly urge the adoption of modern snow technology not currently employed in those areas,” the report said.

Sturm said he has been encouraged by the agencies’ interest in more sophisticated mapping of tundra conditions. A better understanding is needed before anyone allows a fleet of vehicles to crisscross the refuge’s coastal plain, he said.

“You’d have to be brain-dead to not know that this is an area where you really have to know about the snow,” he said.

But it is unknown whether there will be any change in travel rules if oil exploration starts in the area. The Trump administration has vowed to hold an ANWR lease sale before the end of the year, and exploration drilling would follow if that happens.

“What I can tell people about is snow,” Sturm said. “Whether people are listening — I’m 66 years old — I have no idea.”

Lack of consistent snow cover is not the only challenge to safe tundra travel. The ANWR coastal plain also lacks sources of freshwater that would be used to build ice roads, which oil companies depend on for seasonal travel elsewhere on the North Slope.