Arctic sea ice extent gets global attention — but it’s only part of the story

Sea ice extent is important — but that metric can mask variations in other ice measurements such as volume and concentration.

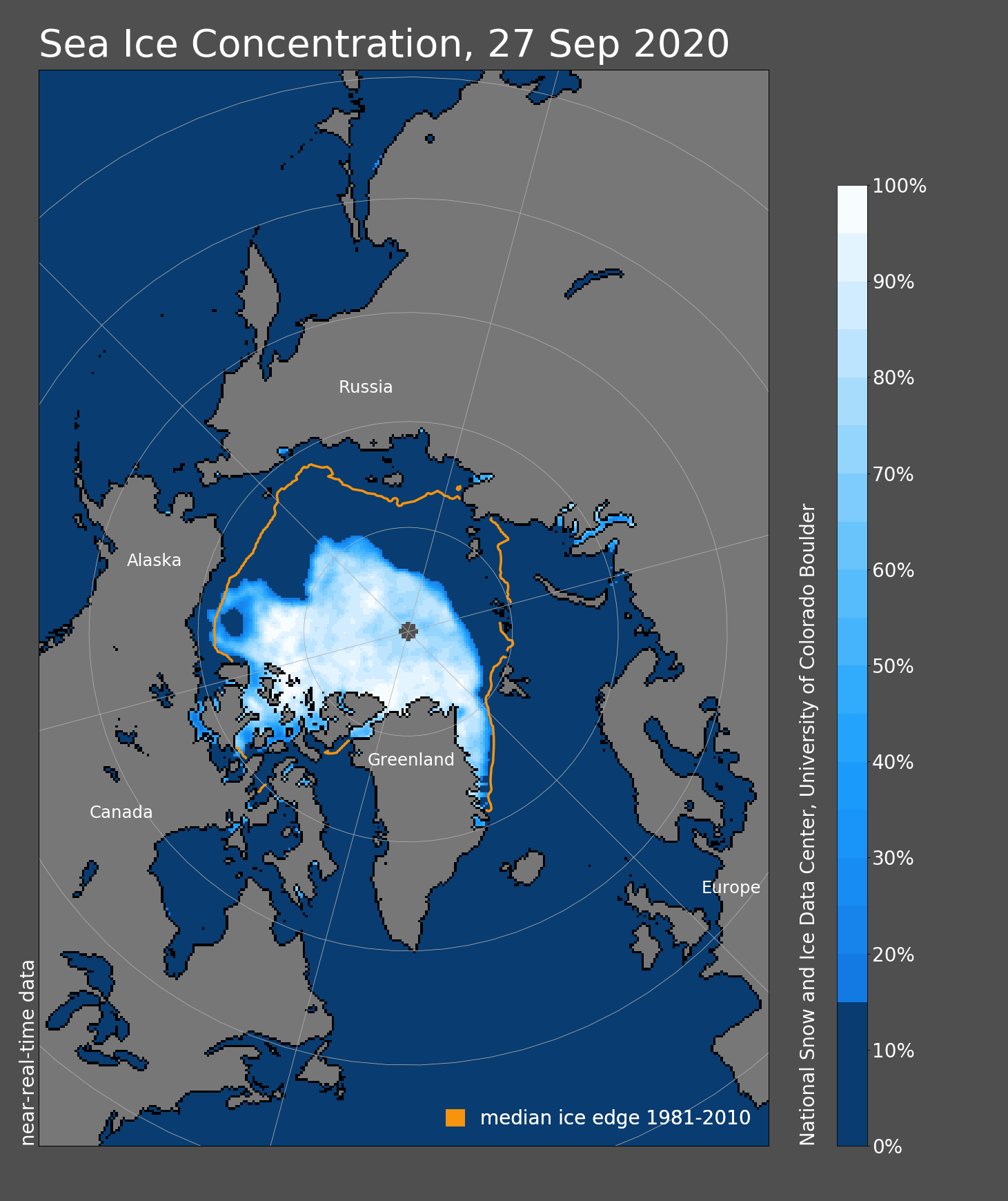

Each September, the world’s attention turns to the Arctic Ocean, where sea ice shrinks to its annual minimum. This year, with the minimum extent hitting the second-lowest in the four-decade satellite record, attention was keen.

This year’s minimum of 3.74 million square kilometers (1.44 million square miles) threatened for a while to break the record-low extent set in 2012; probably only thing that prevented that was a tongue of ice that persisted in the Beaufort Sea, said Brian Brettschneider, a research physical scientist with the National Weather Service.

[Arctic sea ice shrinks to its second-lowest annual minimum extent ever]

But while ice extent receives the most attention, it’s only one way to define the health of the ice, and other measurements can sometimes better explain the complexities of the current condition in the Arctic environment and give clues about conditions to come.

Scientists define sea ice extent is defined as the area where ice covers at least 15 percent of the sea surface — a definition covers a wide variety of ice conditions.

“There is a difference between 100 percent of three-meter thick ice and 16 percent of slush ice. It all looks the same on the extent curve,” said Rick Thoman, a climate scientist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

Scientists do want more than the two-dimensional extent measurements, said Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Colorado.

“What you’d really want, obviously, is volume,” he said.

To understand volume, the University of Washington’s Polar Science Center uses sophisticated modeling that factors in past information. According to the center’s PIOMAS model, annual Arctic ice volume in 2019 was the second-lowest on record. Ice volume in August was the third-lowest on record for that month, according to the PIOMAS analysis. Ice volume has been spiraling downward, according to PIOMAS calculations.

In contrast to modeling, there is now technology that directly measures Arctic ice thickness — NASA’s IceSat 2 and the European Space Agency’s CryoSat satellites, for example.

But the newness of that technology is also a drawback, limiting the time span for which comparisons can be made.

That’s one reason that extent measurements, despite their limitations, are still important markers of Arctic climate change.

The NSIDC’s consistent methodology, taking satellite measurements in the same way since 1979, creates a meaningful decades-long record.

“It’s really an easy metric to monitor,” said Mark Serreze, director of the NSIDC.

It’s also important enough that scientists take great lengths to predict how it will melt. The Sea Ice Prediction Network, a program sponsored by the National Science Foundation, collects forecasts throughout the summer — though most forecasts this summer missed what turned out to be steep decline in ice that brought extent below 4 million square kilometers for the first time since 2012.

Even non-scientists watch the ice, and there may be broader efforts to predict seasonal minimums. “Sports betting is legal now in Colorado,” Serreze quipped.

Ice extent also has one big direct impact on climate change, because ice on the surface — no matter how far deep it goes — reflects sunlight.

“It acts as a big mirror,” said Brettschneider.

But as melt seasons progress, low concentrations and lack of thick layers become more significant, he said. “That thinning ice is going to be more susceptible to wave action to heat from water from below,” Brettschneider said.

Scientists are also interested in how long it takes for open water to refreeze in the winter. In recent years, that refreeze has become much later than in the past; with more open water, more of the heat stored in the ocean is released into the atmosphere, warming weather overall.

“The length of the open water season is really a big, big deal,” Thoman said.

Ever-increasing open-water seasons are directly linked to the warming autumns in Alaska and other parts of the Arctic. For most of Alaska, October is the month with the most dramatic warming over the last 50 years, and northern Alaska is the region that has warmed the most in the month of October — 9.3 degrees Fahrenheit over the last 50 years.

Beyond the emerging technology that allows scientists to measure things such as ice volume, there are some very low-tech tools that continue to be useful.

Scientists tracking changes in the ice have pored over handwritten logs kept by commercial whaling crews and other mariners plying the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort seas long ago. Those Pacific Arctic records, going back to the mid-19th century, have been compiled into a digital atlas.

In that past era, whalers and other mariners ran into much trouble with thick and persistent ice that sometimes crushed their ships. One particularly notorious event happened in 1871, when 33 ships that were trapped in Chukchi Sea ice sank off northwestern Alaska and more than 1,200 members of those whaling crews became stranded.

The month of that disaster: September, the time of year when ice it at its minimum.

In recent years, those same Chukchi Sea waters have seen particularly dramatic ice loss; this year, the Chukchi became effectively ice-free before the end of August, earlier than at any time in the satellite record, just beating out 2012.

Ironically, the recent retreat of sea ice was an important factor that enabled archaeologists to find some of the wreckage of that disaster, NOAA announced in 2016.