Arctic sea ice extent hits a record low for April — and old ice is disappearing fast

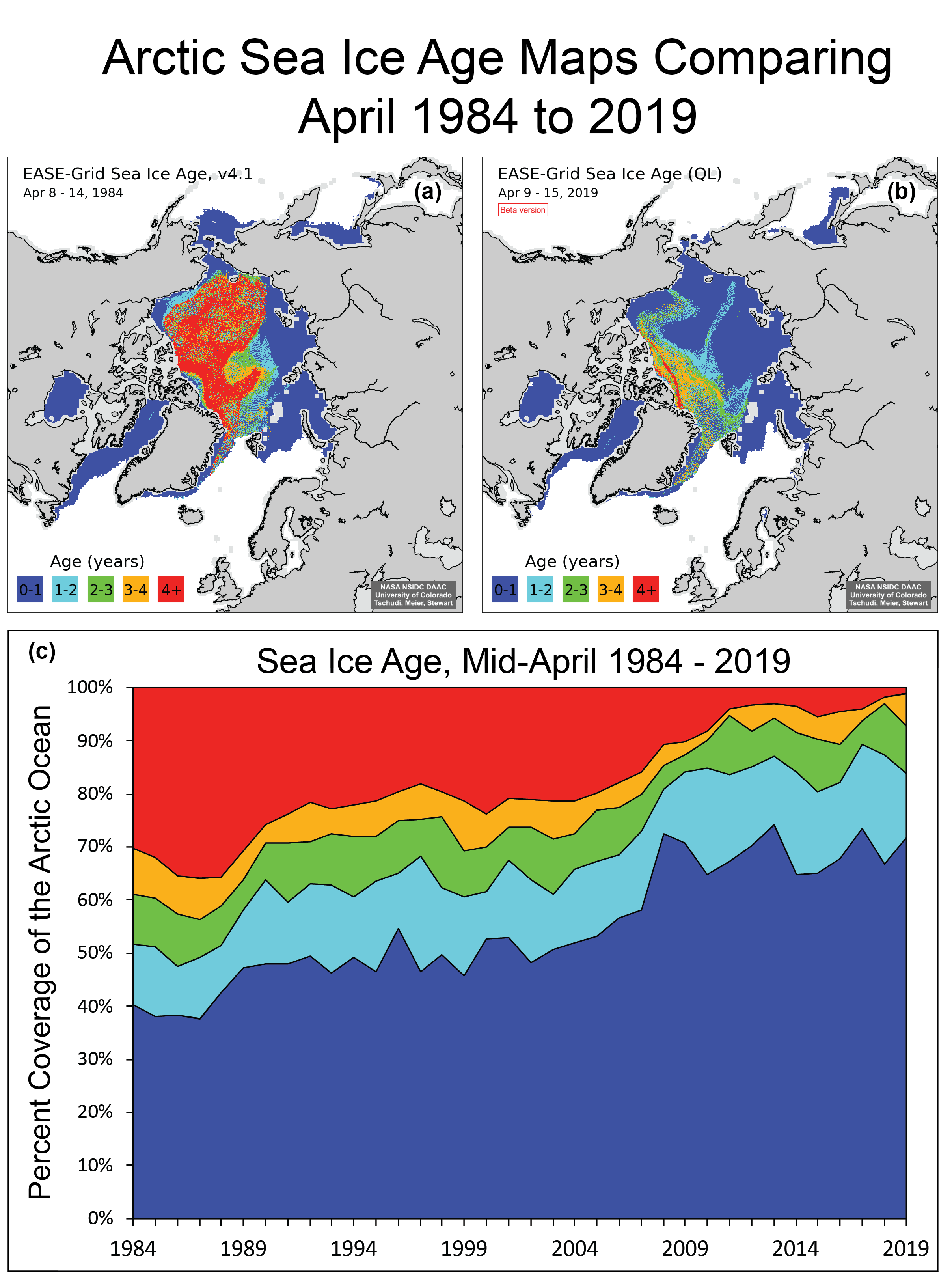

The Arctic is quickly losing the multi-year sea ice that keeps the region from becoming ice-free in the summer.

Arctic sea ice extent last month was the lowest for any April on record, thanks in part to a heat wave early in the month that sent temperatures soaring as high as 9 degrees Celsius above normal, the National Snow and Ice Data Center reported.

Average April sea ice extent of 13.45 million square kilometers (5.19 million square miles) was about 8.4 percent lower than the 1981-2010 long-term average for April and 230,000 square kilometers (89,000 square miles) below the previous record-low April average, which was set in 2016. Ice loss was especially pronounced in the Sea of Okhotsk, which lost half of its ice in the first two weeks of the month, the NSIDC said.

Ice extent is defined as the area where the sea has at least 15 percent ice coverage.

Last month’s status as a new record low for April ice extent is less significant than long-term trend into which the month fits, said NSIDC Director Mark Serreze. That trend is toward not only less Arctic ice but also to far less multiyear ice, according to NSIDC data.

As of April, only 1.2 percent of sea ice in the Arctic was four years old or older, according to NSIDC data. In the late 1980s, about a third of the Arctic’s sea ice was four years old or older.

“We’re losing the old stuff. Much more of it is the young stuff,” Serreze said. And once there is no more ice that survives the summer melt, “then the Arctic will be, by definition, ice-free,” he said.

New ice accounted for about 40 percent of the pack in the 1980s but is now about two-thirds of ice extent, according to the data. That shift is reflected in the quality of Arctic ice.

“Compared to, sat, the 20-year, 1981-2010 average, nearly the entire Arctic has below-normal sea-ice thickness,” said Rick Thoman of the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy.

Through the winter and spring, ice has been low on the Pacific side, notably the Bering and Chukchi seas, and that ice scarcity is reflected in April and early May sea-ice extent data.

The lack of winter Bering Sea has been profound in the past two years, and scientists are studying the impacts that may be cascading in the ecosystem.

It is unclear whether the region has reached a climate tipping point, Thoman said.

“That’s the big debate. Is it a blip or is this the new normal or is this a way station to the future?” he said.

Every year in the future will not be like 2018 and 2019, but it appears that more low-ice winters can be expected in the future, he said. “This might not be the new normal, but this will not be an unusual thing anymore,” he said.

By early May, heat and melt on the Pacific side of the Arctic had had created open waters as far north as the Beaufort Sea off Utqiagvik. That is an early melt for that part of the Arctic, similar to the early Beaufort Sea melt of 2016, Thoman said.

The open waters created by early melt in the Chukchi tell a similar story, he said. “In the Chukchi, the only year that’s had more open water in this part of the season was last year,” he said.