Arctic sea ice isn’t just shrinking in area; it’s also getting thinner

Had November been normal, sea-ice extent might have been somewhat above average for the month.

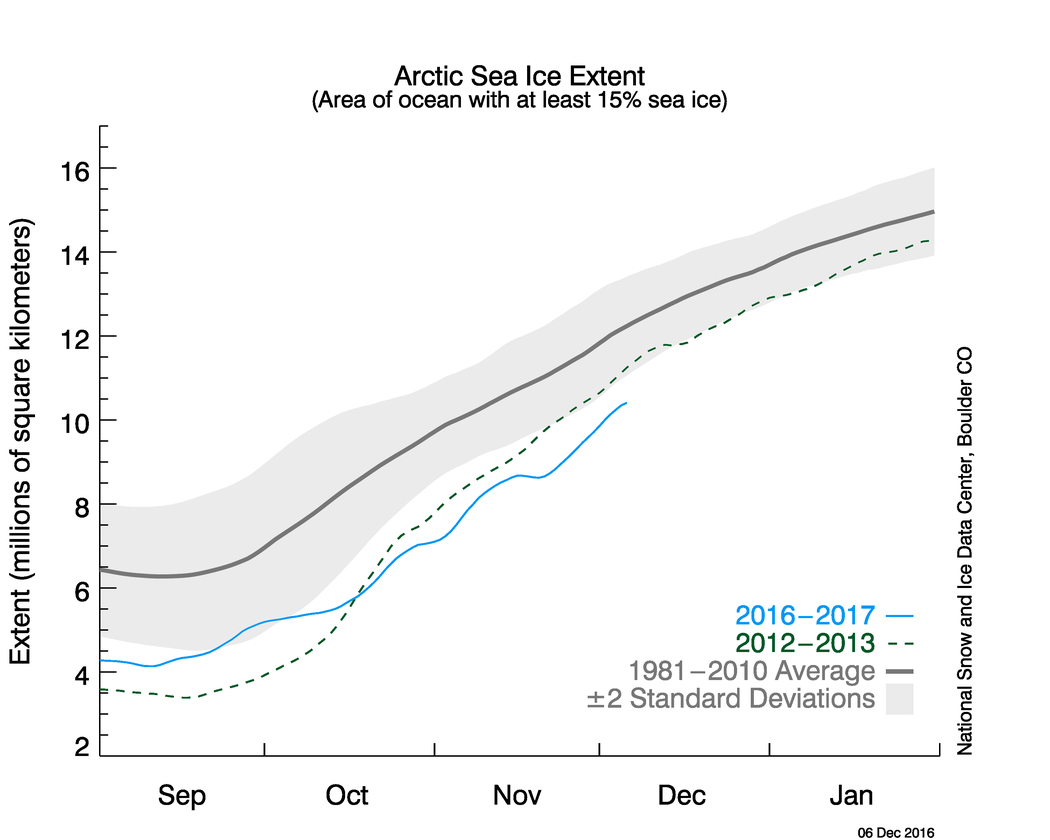

Despite exceptionally warm air and water temperatures in the Arctic Ocean, combined with wind patterns that have hindered ice growth, sea-ice grew at a rate in November that was slightly faster than average than previous Novembers.

But these are not normal times. A mid-month spike in air temperatures, sending thermometer readings close to the freezing point (some 25°C above normal), resulted in sea ice retreating temporarily, an “unprecedented” occurrence during a winter month, according to the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center, a Colorado-based research outfit.

According to the NSIDC’s monthly sea-ice report for November, released today, Arctic sea-ice extent last month was the lowest recorded for the month of November since satellite record-keeping began in 1978. It was the seventh time this year that sea-ice extent has reached a record low for the month.

[Polar sea ice the size of India vanishes in record heat]

Although sea-ice in the Arctic is still in the early stages of its winter growth season, which normally runs from September through until March, the slow start may set up the Arctic Ocean for a repeat of the situation that led to this year tying for the second-lowest summer extent on record.

Climate scientists explain that an early break-up of the sea ice this past March gave open water areas more time to absorb the sun’s energy. So, instead of being at the freezing point as they should be now, many parts of the Arctic Ocean are still as much as 4°C above normal.

With less time to form ice that can withstand the summer melting season, the same types of declines can be expected again in 2017, according to Andrew Shepherd, a professor of earth observation at the University of Leeds.

“It’s really hard to get a month without a record right now,” he says. “We are at a stage where warm temperatures are making record lows increasingly frequent, so that makes it hard to report a new story about the situation.”

Shepherd’s own research focuses on sea-ice thickness, rather than extent. This parameter, by some measures, gives a more accurate picture of the state of sea ice, since it gives an indication of its durability. This is because thicker, older ice is more compacted and more likely to survive from one year to the next, compared with the newly formed ice that is included in extent calculations.

[Earlier: Arctic sea ice isn’t only sparser; it’s younger and thinner too]

While the decline in sea-ice thickness is less pronounced than extent, this, he says, is due mostly to improvements during a single year. Otherwise, data gathered using CryoSat2, a European satellite, indicates that sea-ice thickness has declined in five of the past six years.

The latest information for sea-ice thickness, from November 16, forecasted the monthly volume to tie the record low for the month. This, according to the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling, a UK-based research outfit, is the result of an early winter growth rate that is 9 percent slower than normal.

Typically, sea-ice grows by 161 cubic kilometers a day in November. Based on conditions in mid-November, the CPOM forecasted that growth for the month would be 139 cubic kilometers a day.

At the end of the summer, sea-ice was reportedly thicker than in most other years, meaning that despite its low extent, the total volume of ice in the Arctic Ocean was higher than in other years when the extent was notably low.

While ice thickness in the central Arctic Ocean continues to be ahead of the record-low thicknesses set in 2011 and 2012, the situation is reversed in the Beaufort, East Siberian and Kara seas, which all form part of the Arctic Ocean’s southern fringe.

Rachel Tilling, a CPOM scientist, reckoned that, as with extent, warmer-than-normal temperatures were the culprit here as well.

“Although sea ice usually grows rapidly after the minimum extent in September, this year’s growth has been far slower than we’d expect,” she said in a statement.

It is the same story, regardless of which dimension you look at from.