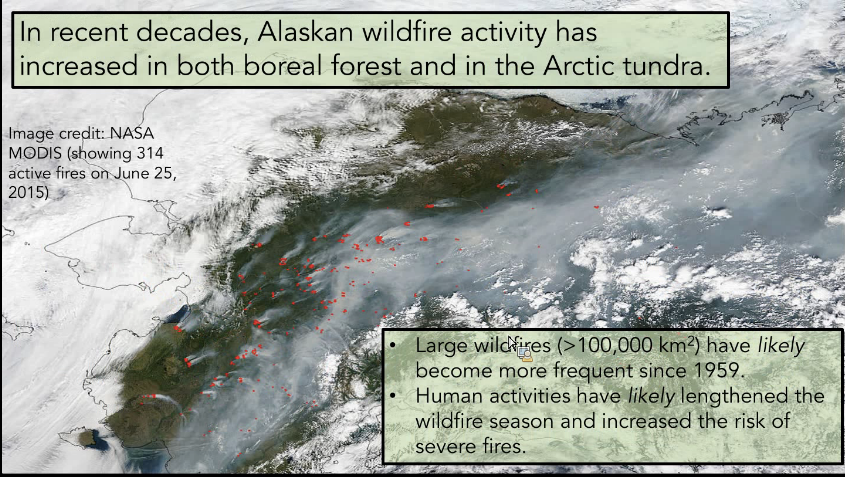

Arctic wildfires will likely become more common and more intense, experts say

Climate change is leading to more (and more powerful) wildfires around the globe -- and the Arctic is particularly vulnerable, experts say.

This summer, the Arctic blazed with wildfires. After long droughts, parts of Sweden, Finland, Russia, and Alaska erupted in flames that even spread into the Arctic Circle.

As many as 80 wildfires raged across Scandinavia, with 11 north of the Arctic Circle. In Alaska, fires gobbled up more than 14,000 acres. In Russia, they swept through vast swaths of forest.

It’s not just the forests in the Arctic catching fire. The tundra is burning as well.

Wildfires are becoming more common and more intense all around the world as the planet warms. But as with many other effects of climate change, the Arctic is disproportionately at risk.

Patrick C. Taylor, a climate research scientist at NASA’s Langley Research Center, recently discussed a report on the causes and consequences of climate change in the Arctic.

Speaking in an online seminar hosted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Taylor discussed how massive and unprecedented environmental changes are already playing out in the Arctic.

One such consequence, he said, is an increase in wildfires.

“The warmer, drier Arctic that’s expected and that’s occurring is making the region more susceptible to wildfire,” Taylor said.

This is a La Niña year, typically associated with cooler — not hotter — temperatures. Even so, many parts of the world saw record-breaking temperatures and devastating fires. Towns located within the Arctic Circle, like Kvikkjokk, Sweden, and Sodankyla, Finland, saw temperatures soar to a scorching 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

Other researchers concluded in July that climate change caused by humans had doubled the chances of a heat wave like the one Europe and other regions experienced this summer.

The higher temperatures and different precipitation patterns associated with climate change often bring about a brutal cycle of droughts and floods — which in turn make those areas vulnerable to fire.

Wildfires have many different causes, both human and natural–from dropped cigarettes to lightning strikes. As climate change accelerates, those natural causes are becoming more common.

The number of wildfires caused by lightning strikes has risen 2 to 5 percent every year for the past four decades; as larger and more powerful storms become the norm, lightning strikes will play a bigger role in starting fires.

Climate change caused by human activity has also lengthened the wildfire season and increased the risk of severe blazes, Taylor said.

These changes may lead to fire patterns not seen in the Arctic in the past 10,000 years, he warned.

To make matters worse, the areas swept by fire may then contribute to climate change, creating a dangerous cycle. Forests, carbon-dense peat, and permafrost devastated by fire release massive amounts of greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide and methane, which in turn exacerbate climate change.

For instance, since fires began sweeping Siberia and other parts of Russia this year, NASA scientists have observed a spike in carbon dioxide and aerosols released into the atmosphere. Fires like these are becoming much more common; Russia has seen a tenfold increase in the number of wildfires in the past decade.

And then there’s the soot from the fires. It darkens the ice and snow, making them absorb more of the run’s rays and accelerating the melting process.

As the Arctic loses its white cover, the darker areas below absorb more and more solar radiation — a phenomenon called the albedo effect.

As alarming as these fires are, however, Taylor says such changes may just be the tip of the iceberg. In Alaska, for instance, the area swept by fires is likely to increase by 25 to 53 percent by 2100.

“The biggest and fastest changes may in fact lie ahead,” Taylor said.