As it approaches its yearly minimum, Arctic sea ice extent is slightly greater than recent ultra-low years

But the extent still shows a clear downward trend — and there are other troubling signs, such as near-record thinness and the loss of much multi-year ice.

Arctic sea ice usually reaches its lowest extent for the year in September, and this year, it appears increasingly likely that impending will be well above the extent measured in most recent years. That’s because cool and cloudy weather in some regions has helped preserve some of the ice this year.

Sea ice extent, as measured on a five-day rolling average, was 4.73 million square kilometers (1.83 million square miles) on Wednesday, the National Snow and Ice Data Center reported. That puts the extent for this time of the year much higher than last year’s near-record low of 3.832 million square kilometers for the same point in the year.

Extent, defined as the area where there is at least 15 percent ice cover, is at about the tenth-lowest spot in the four-decade satellite record, roughly tied with a few other recent years.

But if current Arctic ice extent looks better than it has in recent years, that’s only relative to the very recent past, experts said — and metrics other than sea ice extent, including ice thickness and the amount of multi-year ice, are showing troubling declines.

“I think what’s remarkable is how often we fall below 5 million square kilometers now. Before 2007, that was practically unheard of,” said Zack Labe, a postdoctoral fellow and Arctic ice specialist at Colorado State University.

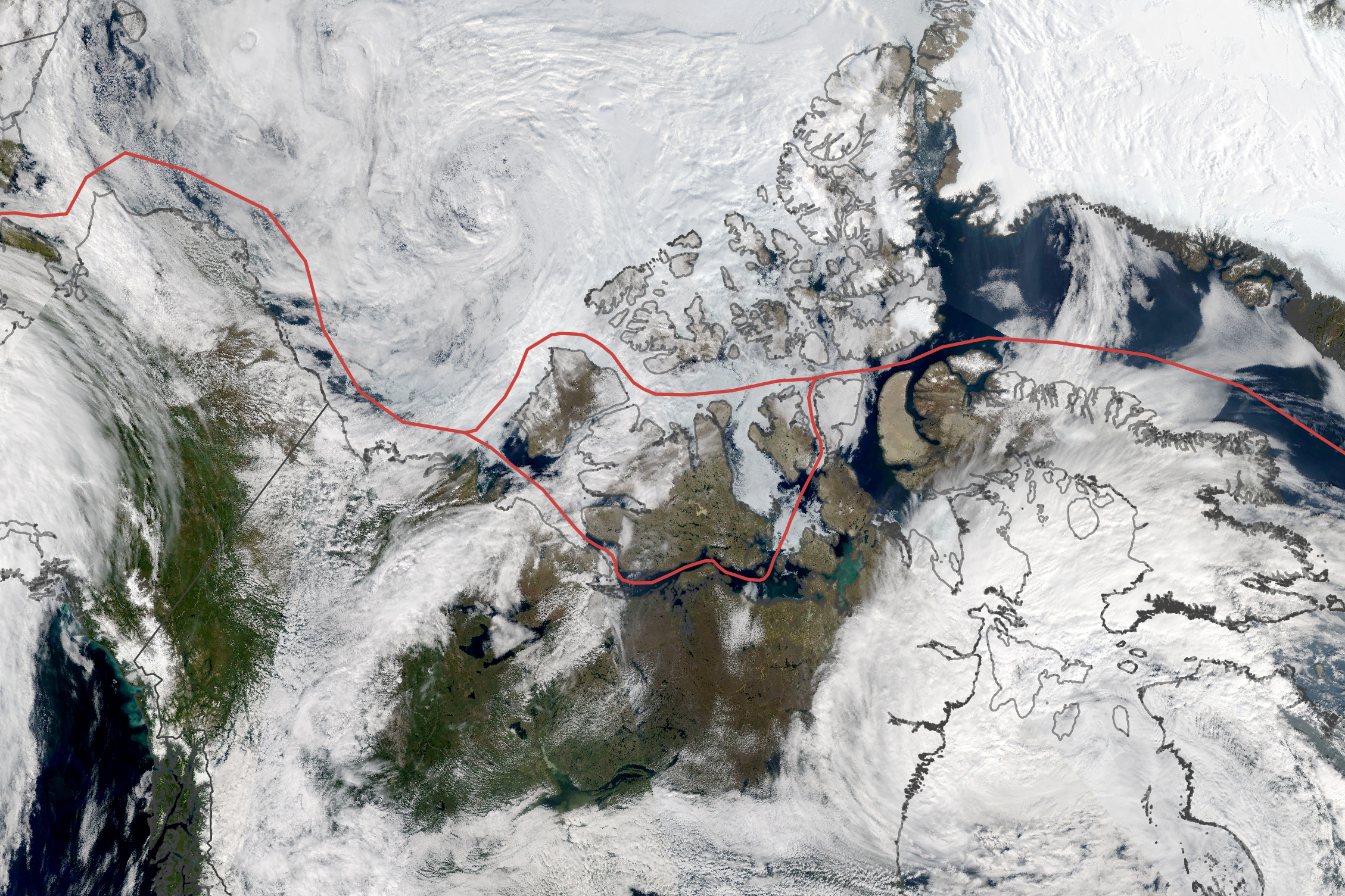

There have also been some stark regional differences.

On the Siberian side of the Arctic, the Laptev Sea had a dramatic and early melt for the second consecutive year.

In 2018 and 2019, there was dramatic melt in a different place, in the Bering and Chukchi seas off Alaska. But this year, the Alaska region is largely responsible for keeping the Arctic-wide extent higher than in the past several years.

Melt in the Chukchi, which is off the northwestern Alaska coast, was so slow this year that total ice extent there equaled the 1991-2020 median for most of the summer.

Rick Thoman, a scientist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy, attributed that largely to a persistent cold low-pressure system over the northern Beaufort Sea that sent northwest winds over the Chukchi. Melt off Alaska stalled in late July and most of August “with that cold low just sitting there and spinning,” he said.

That weather pattern has now ended, and late-season melt in the Beaufort and Chukchi has picked up, Thoman said. He expects the annual Beaufort minimum, which was hit last year on Sept. 13, to be relatively late this year.

Lingering ice in the Chukchi this summer might have given a slight reprieve to Pacific walruses, which in that region use floating ice as a platform for food foraging and raising young.

Walruses did congregate this year at a beach near the northwest Alaska village of Point Lay — as they have almost every year since 2007, when extent hit what was then a record low — but local residents reported that the congregations were much smaller and later than in some recent years, said Andrea Medeiros, a spokeswoman for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The walruses began coming to shore at the Point Lay site on August 24, nearly a full month later than they did last year, she said by email.

Another feature that helped preserve ice off Alaska was the movement of large amounts of old ice into the Beaufort and Chukchi seas, Labe and Thoman said.

But the transport of old ice into areas off Alaska raises problems for the future. Once it drifted into the Beaufort, much of it melted away, significantly reducing the total amount of multi-year ice in the Arctic.

At the start of August, the total amount of multi-year Arctic sea ice was at the lowest ever measured for that time of the year, the National Snow and Ice Data Center reported last month.

Loss of old ice has long-term effects, Labe said. “The climate-change signal is multiyear ice becoming first-year ice,” he said.

Already, data suggests that ice is “very thin,” at a near-record low for mean thickness, even though the extent is higher than in many recent years, he said.

Last month ended with near-record low mean #Arctic sea ice thickness… Each line represents one year of sea ice thickness from 1979 [dark blue] to 2020 [dark red]. Yes, sea ice extent doesn’t tell a complete story.

[Graphs: https://t.co/uzWknWmNnX. Data from PIOMAS] pic.twitter.com/DCovIzlAyC

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) September 8, 2021

Overall, Thoman said, this year is yet another in the long-term trend of diminishing Arctic sea ice.

“Last year we were below the trend. This year, above. But nothing in there is changing the basic trend that we’ve seen,” he said.