As the Arctic warms, scientists at this remote field station try to make sense of the changing environment

TOOLIK LAKE, Alaska — As Alaska’s climate changes, almost every veteran researcher at Toolik Field Station, the Arctic research center just north of the Brooks Range, has a story about lightning.

Linda Deegan, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, was enjoying a beer by Toolik Lake when she saw her first strike. She remembers uttering an expletive when she saw it.

Deemed impossible in northern Alaska only 30 years ago, thunderstorms eventually appeared, likely due to rising temperatures. Then came fire. In 2007, a lightning strike sparked Alaska’s largest recorded tundra fire, which torched 400 square miles just 20 miles from Toolik.

Now lightning is a normal fact of life in the far north. Natural changes make the Arctic one of the most exciting places to study as the region warms faster than anywhere else in the world, say the researchers who spend a few days to a month here. Even with a climate-change doubter in the White House and science, with its objective facts, the subject of skepticism from top elected and appointed officials in Washington, Toolik is a federally funded center where scientists have been studying how the Arctic is changing, among other topics.

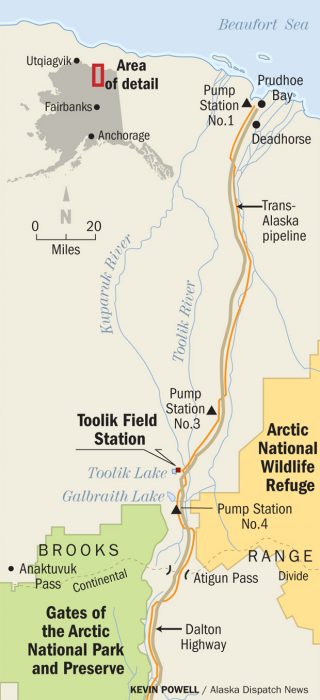

The green tundra and multiple lakes and streams surrounding Toolik Field Station, run by the University of Alaska and located in the shadow of the Brooks Range on the North Slope, are key to studying how Arctic ecosystems — with their complex groupings of reactions and connections — will respond to the changing climate.

Early beginnings

Many scientists at Toolik have the advantage of time.

In the early beginnings of the station, before the words “climate change” took on a political cast, researchers were manipulating the environment to control their experiments, adding nitrogen and phosphorus to some plots of tundra, taking away birch plants in others, all in an effort to observe how systems react in controlled situations. It’s one of only two Arctic stations in the world that house long-term ecological research projects, according to John Hobbie, one of the five researchers who first set up camp at Toolik Lake. (The other Arctic station is in eastern Greenland.)

Toolik can partially attribute its long history to the construction of the trans-Alaska oil pipeline and the Haul Road that supplied it.

In the summer of 1975, the year after pipeline construction began in earnest, a group of scientists took advantage of the newly accessible Alaska tundra and set up camp on an abandoned airstrip near Toolik Lake.

The following year, scientists conducted research in the surrounding area while camping in tents. A modular building nearby served as a combination laboratory, kitchen and dining area.

Over the years the camp expanded, eventually outgrowing the airstrip and relocating to its current spot adjacent to the lake in the mid-1980s.

Even today, Toolik and the oil presence on the North Slope intersect. Scientists at Toolik still take advantage of access roads put in for the pipeline. And according to Syndonia Bret-Harte, co-director of Toolik Field Station, an engineer at Pump Station 4 — the closest neighbor to Toolik — attends the station’s weekly science talks whenever he is on shift.

“It’s all been tied together from the beginning,” Bret-Harte said.

Changing landscape

Using about 25 years of readings, it’s hard to detect a statistically significant air temperature trend in the area immediately around Toolik Field Station. Ed Rastetter, lead principal investigator for the Arctic Long Term Ecological Research Network, says it took 46 years for warming observed at Barrow to emerge as statistically significant.

But there have been other subtle changes in the ecosystem around Toolik, many that require precise scientific instruments to detect.

In January, Hobbie and a group of researchers including Rastetter and Gaius Shaver, both from the University of Chicago-affiliated Marine Biological Laboratory, published an article in the scientific journal Ambio detailing these changes. Among the evidence: an almost 20 percent increase in vegetation abundance.

“Even if you come back year to year, you can’t see 20 percent,” Hobbie said in a phone interview from Toolik. “But if you measure very carefully you can say, ‘Yes, changes are going on.’ ”

Toolik became part of the Long Term Ecological Research program in the late 1980s, serving as a base camp for its Arctic tundra research. The network, created by the National Science Foundation, currently gathers information on environmental changes in 28 unique ecosystems, from Antarctica to the tip of Alaska and from northern cities to temperate lakes.

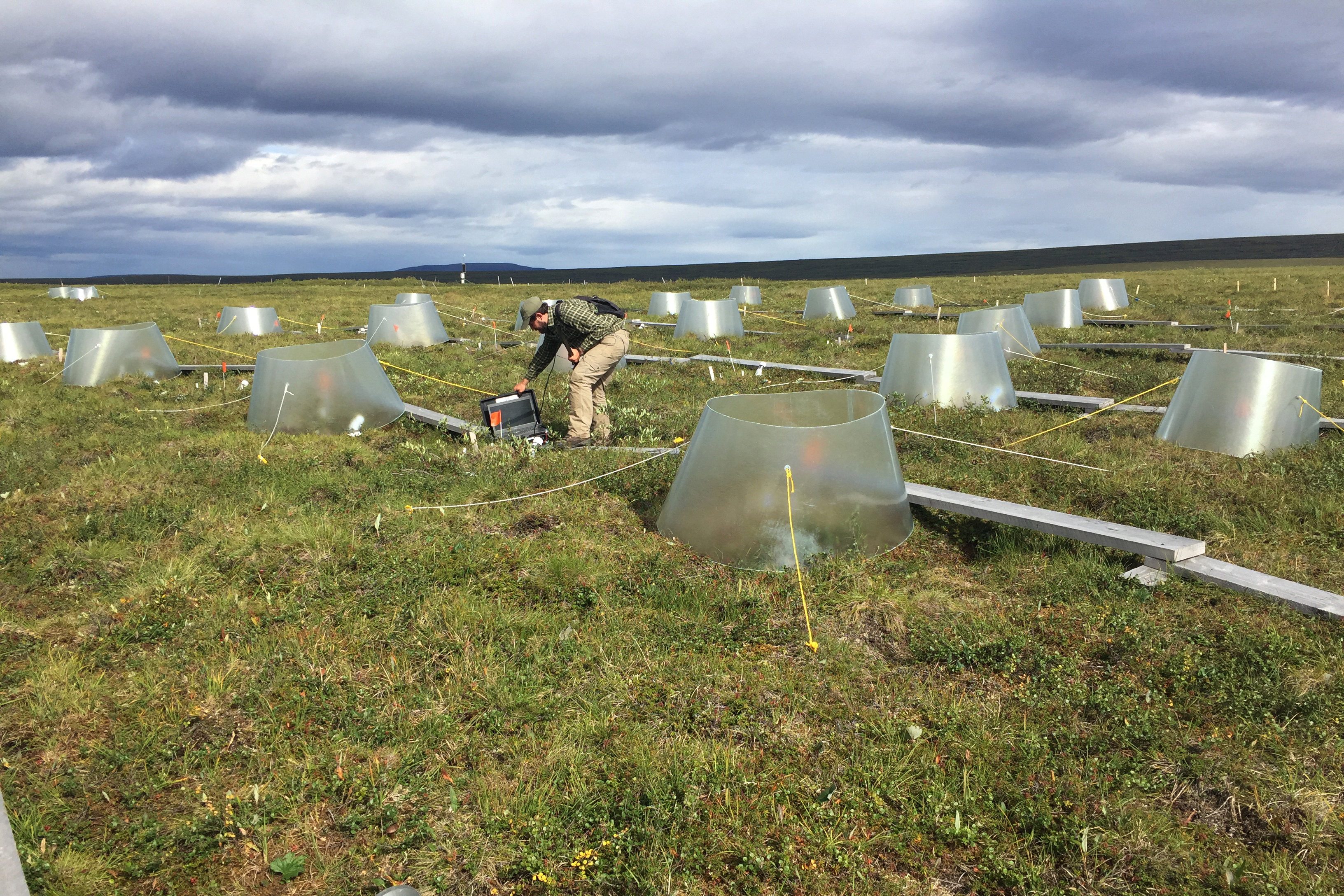

Bits of land being picked apart and analyzed in labs are part of larger plots at Toolik that have been maintained for decades. By studying these plots, along with streams and lakes also undergoing their own manipulations, scientists are trying to understand different components of the ecosystem, and perhaps predict how a warming climate might alter them.

After climbing a small hill behind Toolik Field Station, scientists can witness extreme changes in action. One morning in early August, Rastetter led a tour of some terrestrial experiments, pointing out shade houses that mimic cloudy days and open-air plots treated with doses of nitrogen and phosphorus — two important elements when studying the cycle of nutrients in the area.

At a small greenhouse, its metal frame draped with translucent tarps, researchers led by Shaver have added extensive amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus to tundra over more than three decades. The greenhouse warms the plot.

“Everyone likes this one,” Rastetter said as he walked toward it.

Stripping away one side of the greenhouse, Rastetter revealed plants that were jumbled and twisted from their confined quarters. The birch trees towered over the untouched neighboring grasses outside of the greenhouse.

Shaver said this is a very extreme experiment, with the plants receiving agricultural amounts of fertilizer and the greenhouse supplying a sometimes uncontrolled amount of warming.

These types of experiments can help scientists understand how the tundra may react when the climate warms and more nutrients in the soil are released — effectively fertilizing the plants.

Looking forward

With the addition of a helicopter, scientists at Toolik can now take their research further into once hard-to-reach Arctic lakes, streams and tundra. Electricity and water in labs help them craft more sophisticated studies, according to Deegan, the Woods Hole marine biologist.

“We have a much better understanding of the diversity and variability of the Arctic than I think we did back then,” Deegan said.

The Toolik camp runs year-round and is able to host around 150 scientists and staffers, sporting amenities like 24-hour snacks and homemade ice cream, a fitness center and a sauna. The field station receives about $3 million a year from the National Science Foundation to cover its base operations.

The science support staff at Toolik also helps researchers by troubleshooting their instruments, training them on the proper use of equipment and setting up water systems, among other things. The station’s Environmental Data Center gathers baseline information, including daily temperatures, migratory bird numbers and ice formation and breakup.

The population of researchers visiting Toolik Field Station skews young — undergraduates, graduates and Ph.D. students crowd dining room tables, while older researchers tend to huddle separately, sometimes with a glass of wine. Toolik doesn’t serve alcohol, but researchers can bring their own — a box of Alaskan Brewing Co. beer and empty bottles of wine occupied trailer porches and recycling bins in early August.

Although more than 4,000 miles away from the White House, researchers studying at Toolik aren’t immune to the anti-science rhetoric coming out of Washington.

“The outlook for science funding in Washington, D.C., which is where most of our science funding comes from, is a little questionable at the moment,” said Bret-Harte, the Toolik co-director. “It does seem like the current administration doesn’t think very highly of scientific research.”

In a wide-ranging conversation in Toolik’s dining hall over Reuben sandwiches and matzo ball soup, Rastetter and Shaver touched on U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith, head of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology and a climate-change critic. Smith and a group of fellow representatives were scheduled to visit Toolik in May, but the trip was canceled due to weather.

“I’m sure he knows in his heart that he’s wrong,” Shaver said when talking about Smith’s views on climate. “He just doesn’t have a fallback.”

But even though President Donald Trump has called climate change a hoax and funding cuts for science research are threatened in his 2018 budget request, Rastetter and Shaver think that a shift from climate skepticism to acceptance — and reaction — is inevitable.

“The problem is that the whole system seems to work on a crisis mode — build up to a crisis and instead of avoiding the crisis, you respond to a crisis,” Rastetter said.

Both pointed to education as a key to cut through the confusion surrounding climate change, training the next generation to be able to be critical thinkers and to recognize “fake news.”

“There are bad things that are happening but eventually the truth will win because it has to,” Shaver said. “It always has. It’s been that way for 2,000 years, since Aristotle.”