Big melt season in Chukchi and Beaufort seas affects animals, people and the weather ahead

Sea ice is sparse in Arctic waters off Alaska, and the implications for animals, upcoming winter weather and next year’s ice pack are reported to be profound.

A lack of floating ice forced walruses to the shore of Alaska’s Chukchi Sea earlier than any time on record. Perilous melt conditions forced biologists monitoring Alaska polar bears to cut short their spring field season. Other scientists sailing in the region marveled at the extraordinarily warm water temperatures. A ship, a Finnish icebreaker, made the earliest recorded vessel crossing of the once-impenetrable Northwest Passage, sailing from the Bering Strait to Greenland in July.

And the extra-large expanses of open water are setting up northern and western Alaska for a warm fall and early winter.

In coming months, from the September to November period, there is a 75 percent chance that the North Slope will be significantly warmer than the 1981-2010 average for that fall period, according to the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center.

“This is as dramatic a forecast as we get,” Rick Thoman, climate science and services manager for the National Weather Service in Alaska, said on Aug. 18 in his most recent monthly climate outlook briefing.

For the Arctic as a whole, the summer of 2017 has been a typical melt season — at least in accordance with the new normal, which is far wider open waters and far less sea ice than average levels in a satellite record that goes back to the late 1970s. Sea ice extent, defined as the area with at least 15 percent ice coverage, is running in the general range seen since 2007, though there’s more ice now than the record-low extent in 2012.

But in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas off Alaska, conditions have been extreme. Ice extent has been flirting with record lows for the region, and there is open water father north in the Beaufort Sea that at any time in the satellite record that goes back to 1979.

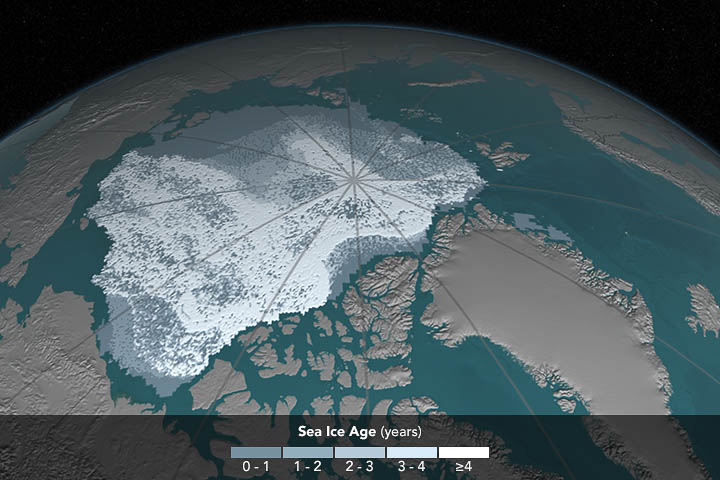

Chalk up the current state to past years’ melt.

“This is the cumulative effect of the loss of multiyear ice,” Thoman said in an interview.

Summer weather over the Arctic Ocean was cool, cloudy and stormy — conditions that slow seasonal melt. But this year’s moderating effect was far smaller than it would have been in the past, said Thoman and Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.

“It seems that the relationship is starting to fall apart because the ice is thinner,” Serreze said. “If the old rules hold, it should have been a fairly high ice year. And it wasn’t.”

The Chukchi, especially, showed evidence of an “unusually strong influx of warm water” through the Bering Strait, Serreze said.

Russ Hopcroft, a University of Alaska Fairbanks oceanographer who was part of research cruises in June and August, saw the results of that.

What did he see in the August cruise?

“Not a speck of ice. We were really surprised,” he said after stepping off the vessel, the Norseman, in Nome.

In June, when he was on an earlier cruise on the University of Alaska Fairbanks-operated research vessel Sikuliaq, he and his colleagues passed through waters with temperatures up to 50 degrees, extraordinarily warm for that part of the Arctic.

“We couldn’t believe it,” he said.

Water contents were also unusual, with very low concentrations in August of the tiny crustaceans known as copepods — creatures crucial to the food web — and high concentrations of jellyfish and other gelatinous creatures and lots of low-nutrition algae, he said.

Walruses, which use floating ice to rest between food-foraging dives, have responded to this year’s conditions.

At a beach near the Inupiat village of Point Lay, walruses clambered ashore early, amassing a crowd of about 2,000 in early August, earlier in the year than at any time on record, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Point Lay walrus congregations have been a nearly annual occurrence since 2007, which was a record-low ice year at the time and kicked off what appears to be a new pattern of advanced annual ice melt. But those crowds usually do not form until later in the year.

Gathering on shore en masse, and far from the choice food sources over the continental shelf, is a dangerous practice for the walruses, especially for those that are smaller and weaker. If disturbed, the spooked animals will stampede back into the sea, putting individuals at risk of being trampled to death.

Despite lots of village and federal warnings urging people to stay away, signs of a fatal stampede have already been seen, said Carrie Labrado, office manager for the Native Village of Point Lay. A tugboat sailed too close to the beach several weeks ago, the walruses fled and several carcasses of young calves were found later at the site, she said.

People also found that that water conditions were different this year, Labrado said.

Locals who like to cool off in summer with swimming breaks in the lagoon and dock area found that the dips were not as refreshing as in other years, she said.

“Usually we cool off in the water real quick. But it was warm water,” she said.

For biologists trying to track polar bears in March and April, ice loss was apparent early in the season.

“None of us had seen anything like we saw this year,” said Ryan Wilson, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist who went out to the Chukchi ice for what was supposed to be a field season running into late April. It was cut short by a week, thanks to ice conditions.

“The last few days we were kind of hopping from ice pan to ice pan, and running out of ice to work on, and also running out of bears,” he said.

The biologists were at the site to put radio collars on adult females, to check weights and body conditions and to monitor movements. In other years, collared bears hung around, but this year the bears, once collared, made a beeline northward to more secure ice, he said.

“It seemed like they knew what was coming before we did,” he said.

What do current conditions portend for the coming months and seasons? More of the same, experts say.

Expect the coming fall and winter months in Alaska to be warmer than normal, especially on the North Slope.

More open water puts more water vapor and heat into the air, creating warmer autumn weather.

That is part of a pattern — linked to sea-ice melt and to spinoff effects — that has established a new type of fall season in northern Alaska.

At Utqiagvik (Barrow), with its long and detailed history of weather records, warming since the late 1970s has been most dramatic in the month of October, researchers have found. At Utqiagvik and at a nearby site, Cooper Island, the snow-free season expanded by 7.46 days per decade from 1975 to 2016, with most of that the result of later snow accumulations in the fall, according to a recent study published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

With past melt creating conditions in which ice will have to form up “from fresh,” freeze-up in the Chukchi and Beaufort is expected to be slow this fall and winter, Thoman said.

“When you’ve got to start over, there’s a limit to how much ice you can grow,” he said.

“The more you lose, the less you have, which means the more you lose.”