Birds in the boreal forest will venture further north as the climate changes

New research shows that boreal bird populations may decline by as much as 70 percent in a changing climate.

Every year, billions of birds migrate north to the boreal forests in Alaska and Canada. But as the climate changes, the paths of some birds are arcing further and further north — and species already living in the north may see massive declines.

According to a new report from the Boreal Songbird Initiative, changes in the climate are shifting the temperature, precipitation, and vegetation of the North American Boreal Forest.

North America’s boreal forest, which spans 1.5 billion acres from Alaska to Newfoundland, is the seasonal home and breeding ground to more than 300 species of birds, including waterfowl, shorebirds, thrushes, warblers and sparrows. It hosts between 1 and 3 billion nesting birds each summer — and about 3 to 5 billion hatchlings emerge each fall. The birds then migrate across Canada and the United States — even venturing as far south as Central and South America.

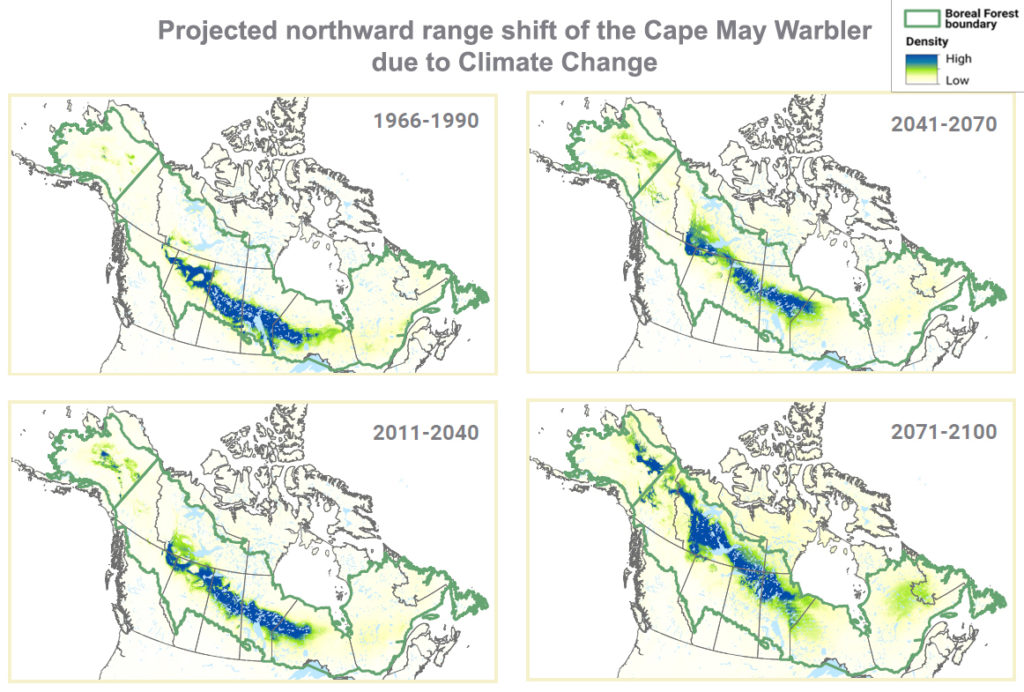

However, as the forest changes, some species are increasingly nesting in more northern regions.

“Most species are expected to exhibit a northward (or upslope in the case of mountainous areas) shift in their distribution in response to climate change,” the researchers write.

The Cape May warbler, for instance, will likely move from the southern reaches of the boreal forest up to the Hudson Bay by 2071.

Other birds will likely move into inland Alaska and northern Quebec.

The researchers note that the Alaska boreal forest is unusual because it already boasts a suitable habitat for many birds found in the Canadian forests — yet few of those birds have made their way northwest.

“This is likely due to a current lack of suitable connecting habitat across the mountain ranges of the western parts of the Northwest Territories and Yukon that has historically been a barrier to their dispersal into Alaska,” they explain.

As the climate changes and the forest shifts northward, connecting those regions, interior Alaska will likely see an uptick in new species — “a phenomenon which is already documented to be occurring.”

However, the researchers point out, forests shift much slower than the climate is changing, so many birds will see a decline in their habitats without a simultaneous expansion north.

These birds — especially those that can’t venture any further north — will see notable declines in their populations as a result.

Of the 53 boreal birds studied, the researchers found that more than half could face population declines — and some might even see losses of 70 percent.

Birds often found in the far north, including Alaska and northern Canada, will experience the biggest losses, they say. The Blackpoll Warbler and Rusty Blackbird will be among the species hit hardest.

“These species are already among the fastest declining birds,” the researchers write. Approximately one billion Blackpoll Warblers have been lost since the 1970s, and the Rusty Blackbird may have declined by as much as 90 percent in the last century.

These species may serve as a canary in the coal mine, as their health and population trends show how these major environmental changes will also affect other animals, plants, and humans.

The authors call for continued preservation of the forest, as it provides a critical habitat for birds. And, as more birds are pushed up from the south as the climate changes, it may become home to even more species.

Preserving this region and its biological diversity will also help Canada reach its commitment, under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, to protect at least 17 percent of its lands and waters by 2020.

One solution may come from the communities within the boreal forest itself. Many indigenous nations and communities, the researchers point out, “are creating innovative models to conserve large landscapes within the forest.”

“Coupled with national and provincial government support, these Indigenous-led efforts offer some of the greatest hope for protecting boreal birds and helping all wildlife become more resilient in the face of a changing climate,” the researchers write.