As Polar Code takes effect, a mixture of confidence and concern

The first thing that almost anyone familiar with the Polar Code, a set of shipping regulations due to come into force on Jan. 1, will tell you is that it is flawed.

This should come as little surprise: the Polar Code, passed in 2014 by the International Maritime Organisation, a UN body, is the result of 25 years of negotiations among 172 countries, with the input of 77 NGOs and 65 intergovernmental bodies, and it must seek to resolve the interests of shippers, conservation groups and communities living along increasingly travelled waterways.

With this in mind, it is a wonder meaningful guidelines wound up being passed at all, according to Lawson Brigham, a professor of geography and Arctic policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and a former Coast Guard captain with experience sailing polar icebreakers.

“Maybe it’s not strong enough yet,” he says, “but it is better to implement it now than to talk about it for another 25 years.”

Brigham, like other maritime professionals, chooses to focus on the long list of regulations governing navigation in the Arctic and Antarctic that the Polar Code contains, including ship design, equipment, training, search and rescue, as well as environmental concerns.

Even with the Polar Code’s flaws, being able to agree on any rules at all represents a “seminal” development, he argues. “There are very few circumpolar frameworks for the Arctic or for the polar regions, but here we have an international agreement that will offer a measure of protection for the environment and ships’ crews.”

Detractors, typically in the conservationist camp, tend to see the Polar Code for it for its shortcomings. Many are diplomatic, making sure to call it ‘a good first step,’ or words to that effect, before listing the areas where it can be improved. Others are more direct, warning that, for all the Polar Code’s good intentions, it can do little to stop an accident from happening, and will do even less to limit environmental damage in the event one does.

“The IMO and industry seem content to dismiss or put off discussion on issues that really matter – that would truly diminish shipping’s impacts on the sensitive Arctic environment and the region’s residents,” John Kaltenstein, a marine-policy analyst with Friends of the Earth US, a conservancy, said in a statement released in 2014 in connection with the vote to adopt the Polar Code.

At the top of conservationists’ list of things that need to be improved is the lack of a ban on the use of heavy-fuel oils in the Arctic. Such fuels were banned in the Antarctic starting this year, and including them in the Polar Code would have addressed two concerns with a single measure, firstly by protecting the environment from a hard-to-clean pollutant, and, secondly, by keeping the air free of the sooty exhaust burning these fuels creates, which is linked to both health problems and melting sea ice.

Brigham recognises that heavy fuels need to be addressed, but he argues it is wrong to say that environmental concerns are the Polar Code’s weakest aspect.

“The code is focused on three things in particular: the ship, the people on board and the environment. If something was left out, it was the people on shore.”

Not having a section on people sends an unfortunate message, he believes, but he expects that such concerns will be addressed at a later date. Of more immediate concern are the rules that will come into effect next week.

One worry is whether they can be implemented properly. Although ships must start complying with the Polar Code on Sunday, in reality it marks the start of a one-year phase-in. This, Brigham reckons, should be plenty of time to equip ships with the equipment mandated by the Polar Code, including things like survival suits, enclosed lifeboats and de-icing equipment, but he is uncertain crews will be able to receive the training they need in time.

“Having all the gear you need on board will only help you so much if you lack the basic training in how to use it,” he says.

A second issue is enforcement. Brigham points out that while the country where the ship is registered will be responsible for making sure ships meets Polar Code guidelines, it will be port states that will be required to enforce them. “In a situation like that, problems are bound to arise,” he says.

Rather than seeing the Polar Code as a bare minimum, supporters prefer to describe it as a starting point for navigation on shipping lanes that have yet to reach their full potential.

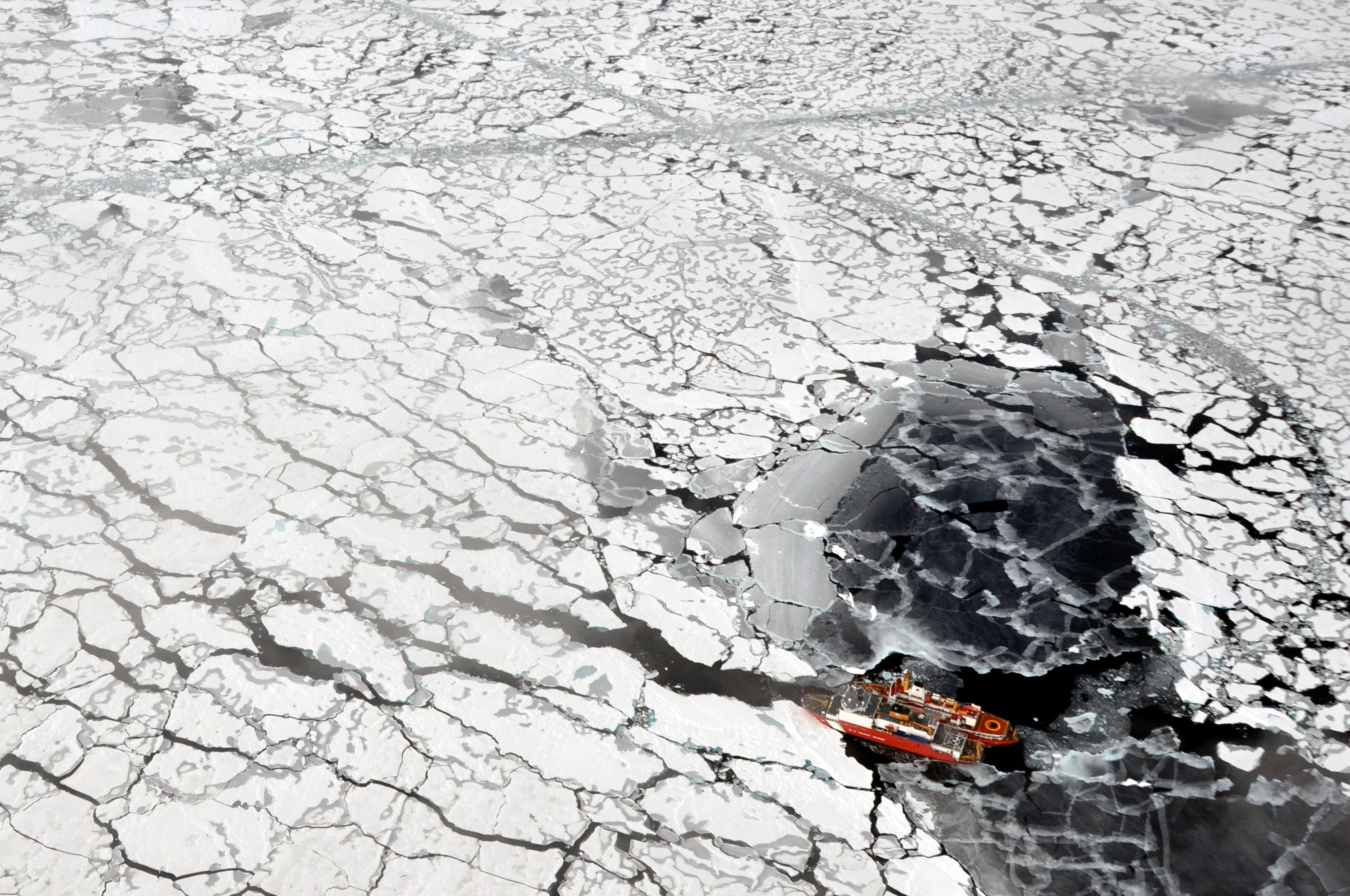

As the ice retreats, “the sea becomes a highway, not a barrier,” explained Marit Berger Røsland, a senior official in the Norwegian Foreign Ministry, during this year’s during Arctic Circle, an annual conference. This will bring more ships, she said. If this is the case, then the Polar Code lays out the necessary rules of the road.

That they are not entirely in place, Brigham repeats, is no reason to scrap them entirely.

“There are lots of questions about the Polar Code,” he says, “But the most important one, I would say, is ‘Would you sail without it?’”