Busting the 2,000-acre myth about drilling in Alaska’s Arctic refuge

ANALYSIS: Claims that oil and gas development in Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge would have a tiny, inconsequential footprint are misleading at best, and unfounded at worst.

The recent Republican tax bill, signed into law by President Trump, calls for two oil and gas lease sales in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

A series of public hearings on those sales begins this week in Kaktovik, Alaska, while an expected set of court challenges are likely to delay them.

That means you’re likely to hear a lot more rhetoric on the subject — and probably one dubious claim in particular.

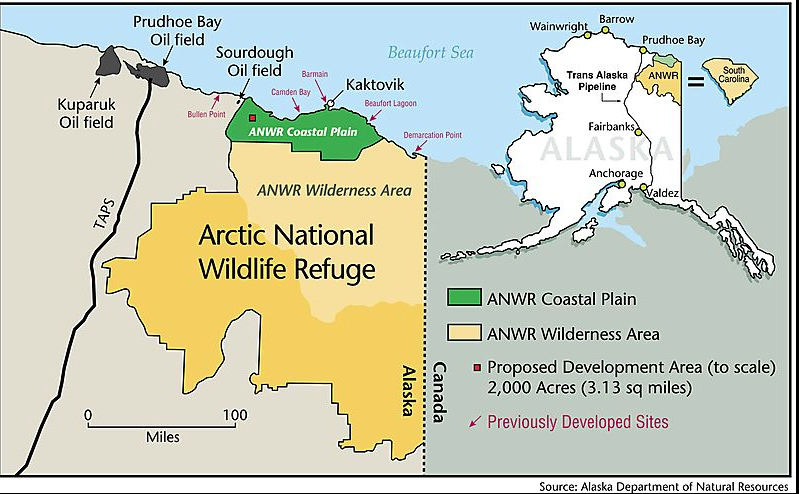

Every advocate of oil development in the refuge claims it would be confined to a tiny speck on the map of Alaska, an insignificant plot covering 2,000 acres and nothing more.

An Anchorage Republican state senator, Cathy Giessel, called it a “postage stamp on a football field.” Former Gov. Sarah Palin said it would be like a welcome mat on a basketball court.

Rep. Don Young touched his nose with a pen at a hearing last year and said the tiny ink spot represented all that would happen in ANWR.

“Two thousand acres,” Sen. Dan Sullivan told Neil Cavuto on Fox News in December, “that’s smaller than the Fargo, N.D. airport.”

The myth of the minuscule ANWR oil footprint had already become conventional wisdom in 2008 when a Texas Republican stood before the House of Representatives, and gestured to a nearly invisible “little bitty red speck” on a big map of Alaska, claiming the oil facilities would be limited to that speck of the so-called 1002 area.

“It takes glasses to see it because it’s only three square miles. To put it in perspective, the Houston Intercontinental Airport is five times the size of this speck,” Rep. Ted Poe said.

Industry officials and the Alaska congressional delegation have been circulating the misleading maps with red specks for years.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski dragged out the political prop during a hearing last year, neglecting to say that instead of a single spot, oil field facilities and pipelines could be spread over hundreds of square miles if oil is found on the refuge.

Even the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service — on a site that no doubt will be revised when Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke discovers it — admits that, despite the 2,000-acre claim, “it could be possible for facilities and their accompanying roads and pipelines to spread in a network throughout the entire 1.5 million acres of the 1002 area.”

The effort to downsize development projects to reduce political opposition has a long history in Alaska. When the trans-Alaska pipeline was under consideration in the 1970s, proponents said it the entire thing would only cover 12 square miles, or about 7,700 acres, so it was no big deal.

The total eventually rose to 16 square miles, still advertised as a sliver that did not change the landscape.

But with both the oil pipeline and the proposed development of the refuge, statistics can be used to distort reality.

The impact of an 800-mile pipeline crossing the state cannot be translated into square miles any more than the impact of major oil facilities in ANWR — with hundreds of miles of feeder lines, pipelines and roads — can be conveyed simply by acreage.

In 1987, an Environmental Impact Statement conducted by the Reagan administration concluded that development of three separate oil fields would require 12,650 acres spread across the refuge for “drill pads, related facilities, air strips, haul roads, pipeline rights-of-way, etc.,” according to testimony given by Bill Horn, a former staff member with Rep. Don Young who went onto the Interior Department.

Horn told Congress that the department expected no big impacts on wildlife, but there would be a “change in the wilderness esthetic character.”

Drilling would require a web of facilities across hundreds of miles connected by pipelines.

After that 1987 report supporters of drilling began to say that 12,650 acres was no big deal, about the same amount of land under Dulles International Airport.

This conveyed a false impression that stuck — that development would take place in a single compact site.

Eight years later, Young said: “The area the oil development would affect consists of only 12,000 acres in the coastal plain – about the size of Dulles Airport.”

But an off-the-cuff remark by an oil industry veteran on Aug. 2, 1995 helped create the 2,000-acre talking point that persists.

Sen. Frank Murkowski chaired a hearing that day on prospects for developing the northeast corner of Alaska, an effort that ended with a veto by President Bill Clinton.

Roger Herrera, a former BP official who lobbied to open ANWR, said, “If today an oil field was built on the coastal plain — a series of oil fields, you would not occupy more than 2,000 acres of footprint. And in the future you can bet your boots it’s going to be reduced even more,” said Herrera.

“2,000 acres? said Murkowski.

“That is correct,” said Herrera.

“That is not much,” said Murkowski.

“It is not much acreage, no,” Herrera said.

The 2,000-acre number, which was not derived from scientific analysis of the refuge, became a powerful and deceptive lobbying weapon. The statistic made it easier to claim that no reasonable person could find oil development objectionable, since development would be confined to a spot smaller than any big airport.

In 1987, the Interior Department said roads and pipeline rights of way were included with the 12,650-acre estimate.

The 2,000-acre total includes airstrips and the land under piers to support elevated pipelines, but not roads and the hundreds of miles of pipelines and feeder lines that would come with successful oil development.

Moreover, it is not clear that there would be any enforcement of a 2,000-acre limit or consequence for exceeding the total.

And there is every reason to believe that once development begins, there will be efforts to ignore the number if enough oil is discovered, as that would create a powerful economic motive for a larger footprint.

Columnist Dermot Cole lives in Fairbanks. Write him at de*********@gm***.com.

The views expressed here are the writer’s and are not necessarily endorsed by ArcticToday, which welcomes a broad range of viewpoints. To submit a piece for consideration, email commentary (at) arctictoday.com.