Canada, Denmark agree on a landmark deal over disputed Hans Island

The two countries have agreed on a land border that divides the island, which is equidistant from Greenland and Nunavut.

With a single sweeping deal, Canada and the Kingdom of Denmark have resolved a 51-year-old territorial dispute over Hans Island in the Kennedy Channel between Nunavut’s Ellesmere Island and Greenland’s far north. The deal also finalizes the maritime border between Canada and Greenland — the longest maritime border in the world.

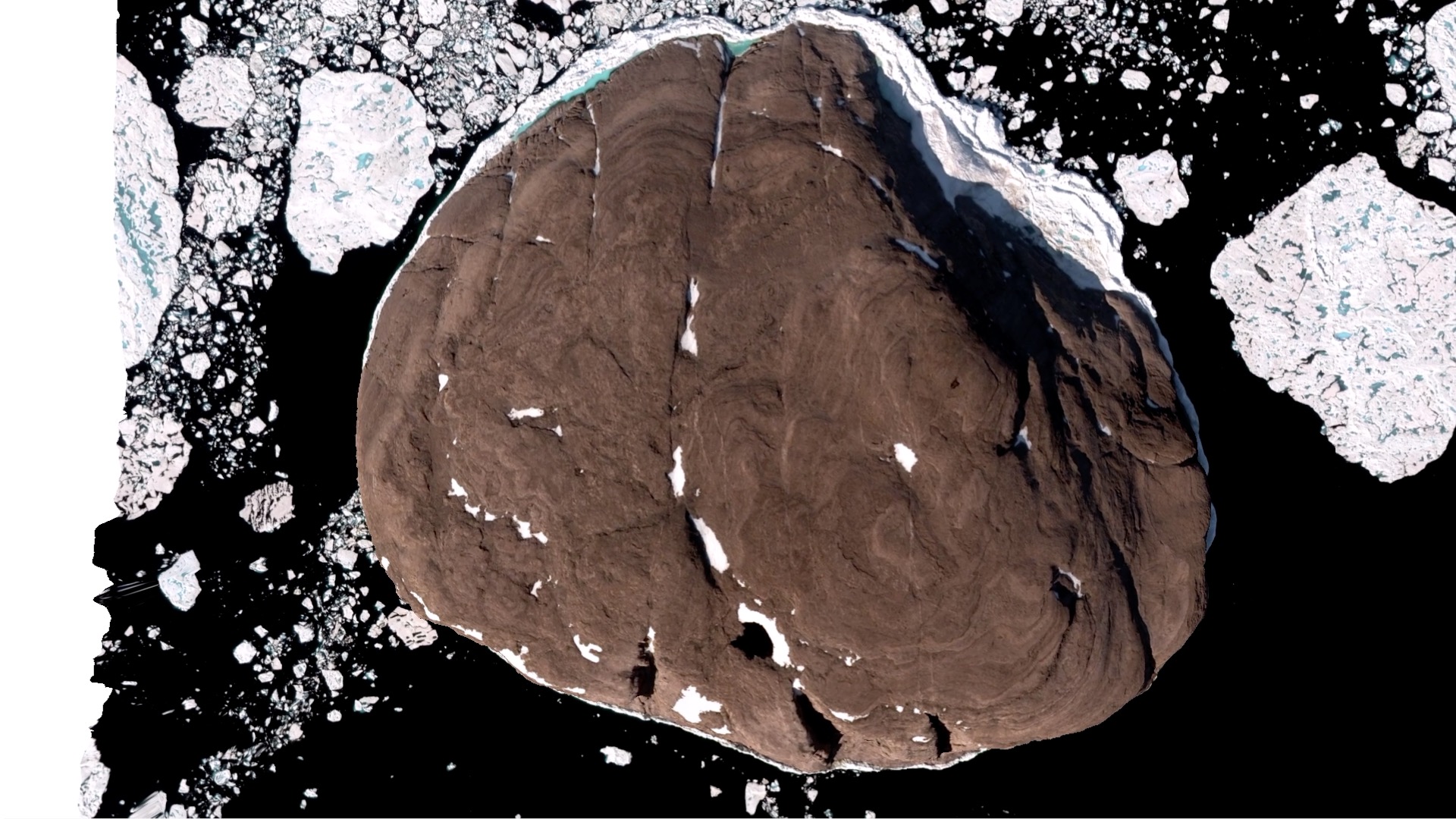

Hans Island will be divided into two parts, with the Greenland part slightly larger than the Canadian. The difference occurs because the new border will follow, in line with international norms, a natural phenomena; a rift in the surface of the island that runs from north to south — almost, but not quite, through the middle of the island.

According to the information available, none of the officials involved in the negotiations have visited Hans Island, but the rift on the island that will now be used as the basis of the new border is easily seen on satellite images that have been available to the negotiators.

The border will run from a small bay on the northern shore of Hans Island across the island to its steep southern precipice. Almost 60 percent of the island will be part of Greenland, including the island’s highest point, while the rest will belong to Canada. Both parties will own part of the bay on the north shore; the only landing place on the island.

At the same time, negotiators have agreed upon the northernmost end of the maritime border between Greenland and Canada in the Arctic Ocean and the southernmost end in the Labrador Sea, with most attention going to the Labrador Sea.

Canada and Denmark, which still holds sovereignty over Greenland, have disagreed for years about the rights to 79,000 square kilometers of seabed in the Labrador Sea, where oil or mineral extraction may be possible in future. According to the new deal the disputed piece of seabed will be split in two; again the Greenlandic part slightly larger than the area allocated to Canada.

Copenhagen and Ottawa both hail the deal as proof that mutually beneficial solutions to difficult territorial disputes can be reached on the basis of international law:

“It is an extremely fine signal to the whole world that you can solve territorial disagreements in a constructive way based on international law. It is exactly this type of message we need in a time when international law is under attack, in particular, of course, by Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine,” Denmark’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Jeppe Kofod told ArcticToday.

Message to Moscow

In Copenhagen, before traveling to Ottawa for the formal signing of the deal, Jeppe Kofod told ArcticToday that he expected the new deal to also have a positive influence on future negotiations with Russia over the seabed in the central parts of the Arctic Ocean. There, Canada, Russia and Denmark/Greenland have all made claims that overlap by several hundred thousand square kilometers.

“Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a wholly unacceptable attack on international law” Kofod said. ”But everybody knows how important the Arctic is to Russia. In that region in particular they will have an interest in peaceful cooperation, even if there is conflict in other areas of the world. The agreement between the Kingdom of Denmark and Canada serves as an example that it is possible. They can tell now that it is possible to reach a result where everybody is a winner.”

Island politics

Hans Island is name Tartupaluk — or “kidneyshaped” — in Greenlandc. It lies in the Kennedy Channel, a mostly frozen strait separating Canada’s Ellesmere Island and the very north of Greenland, some 650 kilometers east of Grise Fiord, the closest civilian settlement in Canada, and 350 kilometers north of Siorapaluk, Greenland’s northernmost township.

Hans Island has an area of 1.25 square kilometers, and its tallest point extends 183 meters above sea. Much of the island’s rock face rises vertically out of the sea; only to the north does it slant more lazily towards the ocean, offering potential visitors scalable access to its flat upper surface.

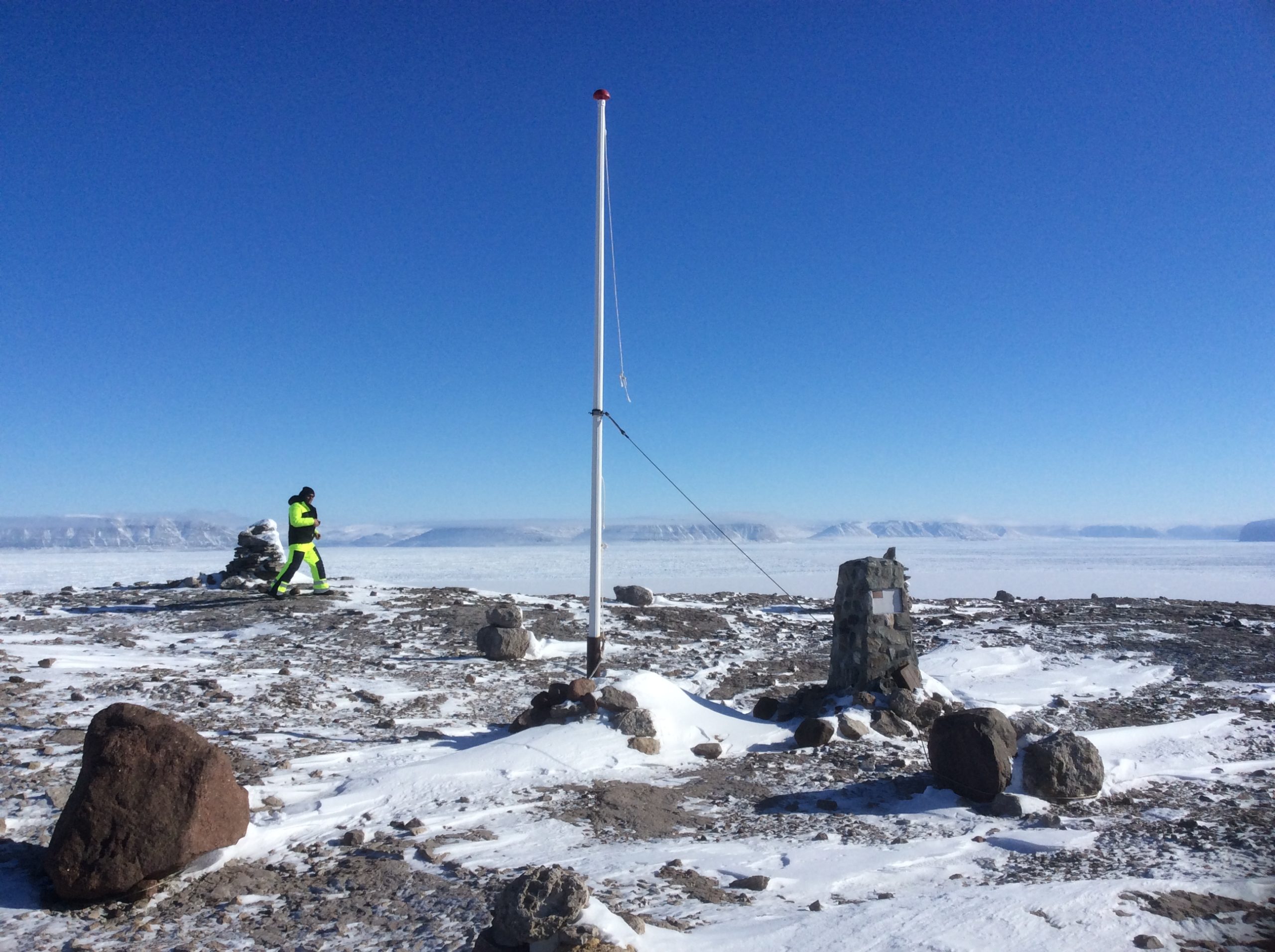

Most importantly, the islands lies exactly midway between Canada and Greenland. From a visit to Hans Island in 2018 this author remembers the unimpeded frosty views towards Greenland and Canada, both only 18 kilometers away. The island itself appears void of vegetation, its rock floor rounded by the violent storms that used to tear flags hoisted by the Danish soldiers to shreds.

The final compromise on the island border was agreed upon at what has been described as a diplomatic marathon in Iceland in November 2021. Final signatures are to be added to the deal Tuesday in Ottawa by Canada’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Melanie Joly and Denmark’s Kofod. Also signing will be Muté B. Egede, chairman of Naalakkersuisut, Greenland’s self-rule government.

The deal seems unlikely to cause much controversy, and independent observers find it laudable:

“This is the solution I have suggested for decades. You will not hear me pointing out all the faults. I can’t see any,” says Michael Byers, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Global Politics and International Law at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

No rewards

Parts of the maritime border between Canada and Greenland were previously agreed upon in 1973. Negotiators drew a line in the ocean to the shores of Hans Island, but they left the controversial issue of a terrestrial border on the island unresolved.

The lack of a final agreement has pained both sides ever since, even if the island offers basically no material rewards. Geologists at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland told ArcticToday that there might be deposits of zinc and lead on the island, but also that the island is so tiny that commercial mining is very unlikely. Any oil in the adjacent seabed will be more than 400 million years old and either gone or too old to be of use.

Strategically, Hans Island is regarded as equally irrelevant. There are often rumors of Russian submarines in Greenland’s waters. Also, Thule Air Base, the U.S. air base in northern Greenland, lies only a short flight to the south, but Hans Island has spurred no interest from the armed forces of any nation.

Politically, however, the island has long played a role.

In 1984, a Danish minister in charge of Greenlandic affairs raised the Danish flag on Hans Island, thereby initiating decades of national posturing by both Canada and Denmark. From 2000 Danish visits to the island became more frequent as old flags were replaced by new ones. Canada protested in diplomatic notes to Copenhagen, and in 2005 Canada’s then minister of defense landed on Hans Island in what was dubbed Operation Frozen Beaver.

A Danish flag was taken down and confiscated and, according to legend in the Danish foreign service, formally delivered to the Danish embassy in Ottawa in a cardboard box from a local bakery. Legend also goes that Danish and Canadian troops left bottles of spirits to each other whenever on visit to Hans Island; the media has often referred to the conflict as “the whisky war.”

Following the Canadian removal of the Danish flag, Denmark dispatched a naval ship towards Hans Island to raise a new flag. Before the ship reached the island, however, the foreign ministers of Denmark and Canada met in New York and agreed to replace any further gesturing with diplomatic efforts to resolve the issue.

Still, for years, nothing was solved.

Conservative governments in Canada, in particular under the leadership of Prime Minister Stephen Harper from 2006 to 2015, emphasized Canada’s intention to defend by any means its sovereignty in the Arctic.

“Stephen Harper would never have agreed to a partition or to give up Hans Island,” Byers told ArcticToday.

In 2018, diplomatic efforts picked up speed, reportedly on Canada’s initiative. A joint task force, working quietly behind the scenes, was to finally end the affair. In 2015, Canada’s Liberal prime minister Justin Trudeau had taken office, eager to better Ottawa’s relations with Canada’s Arctic communities, and the work on outstanding border issues progressed. The Trudeau government favors the kind of value-based foreign policy also pursued by the current Danish government, in office since 2019. After half a century, diplomats eyed a solution.

Inuit influence

On the Danish side, diplomats from Greenland and Denmark worked in tandem to also satisfy Greenlandic wishes. In the preamble to the new arrangement, promises are made that inuit in Greenland and Canada who used to travel on the ice between Canada and Greenland without regard to any borders, will still be able to enjoy unhindered mobility, hunting and fishing. Before the final settlement was reached, officials from Nuuk and Copenhagen twice travelled to Qaanaaq and Siorapaluk, Greenland’s northernmost settlements, to consult with the local communities.

In the preamble to the new deal, there is mention of the Pikialasorsuaq Commission, established in 2016 by the Inuit Circumpolar Council to investigate avenues towards joint Inuit control over Pikialasorsuaq, or the North Water Polynya, a vast polynya famous for its abundance of wildlife in the same strait as Hans Island. In the new deal, the governments of Denmark and Canada promise to look at further options for increased Inuit control over relevant matters in the area.

“We will establish a border, but I hope that the border will in fact draw people closer together. The idea is that the practical implications of the border should be minimized to the benefit of those who live in the area and have lived there for generations without being preoccupied with borders,” says Kofod.

“The most important is the work that follows to secure cooperation after the agreement on the border. That people are free to move, secure agreements on fish stocks and other resources; anything that is relevant to this geographical area. This will not be up to the Danish government, but to the government of Greenland,” Kofod told ArcticToday.

In Canada, Aluki Kotierk, president of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. (NTI), the legal representative of the Inuit of Nunavut on native treaty rights and treaty negotiation, hailed the deal in a statement to the Toronto-based Globe and Mail:

“The dispute between Canada and Denmark over Tartupaluk or Hans Island has never caused issues for Inuit. Regardless, it is great to see Canada and Denmark taking measures to resolve this boundary dispute,” Kotierk said.

“As geographic neighbors with family ties, Inuit in Nunavut and Greenland recognize the significance of working together toward our common future. NTI expects this long-standing relationship between Inuit in Nunavut and Greenland to be a symbol of continued co-operation between Canada and Denmark,” she said.

And who is Hans?

Suersaq, who signed his name Hans Hendrik when working for foreign expeditions, was a Greenlandic hunter and doghandler, serving between 1853 and 1883 as a guide, translator and provider of food for five Arctic expeditions. His close encounters with polar bears, grumpy expeditioners and wrecked ships are depicted in his “Memoirs of Hans Hendrik, The Arctic Traveller,” translated from the Greenlandic in 1878.

In the south of Greenland, he and his family were attached to the German mission of the Herrnhuts, until, in 1853, Suersaq took hire with an American polar expedition. His mother, who had recently been widowed, begged him to remain at home, and his farewell-promise burned itself into his memoirs: “If no mischief happen me, I shall return, and I shall earn money for thee.”

Hans Hendrik, however, never returned home. He settled in the north of Greenland. He found life appealing there with plenty of walrus, seals and bears. He married, raised a family and for a series of still more adventurous American and European polar expeditions, he made survival possible.

Notorious in particular were his efforts when in 1872 half of the American Polaris Expedition, who had set sail for the North Pole, got separated from the main party in the ice north of present day Thule Air Base. For seven months the group survived in igloos on ice floes. Also Hans Hendrik’s wife Mequ and their three children, the youngest only a couple of years old, had to make do as waves and heavy currents cut piece after piece off their floes. Meanwhile, the seemingly indefatigable Hans Hendrik and a Canadian inuit colleague hunted seals and bears, meat for the hungry and blubber for their oil lamps. Life was sustained, all survived, saved at the last instant by an American seal hunting vessel after drifting more than 1,500 kilometers at sea.

Hans Hendrik had an island named after him (actually two, but according to Danish author Jane Løve, the other is more of a rock than an island). The naming of Hans Island took place during the better days of the Polaris Expedition in 1871. Expedition leader C.F. Hall pointed out the island, named it, but then died a few months later. The name stuck, but we have no knowledge of C.F. Hall’s reasoning behind it.

After the naming of the island, 100 years passed before Danish and Canadian negotiators, about to draw a border at sea between Greenland and Canada, discovered that the island lies on exactly equidistant between Denmark and Canada.

The new deal may well be the end of Hans Island’s fame.

“That could certainly be one of the outcomes. In 20 years from now, perhaps nobody will be speaking about Hans Island anymore,” says Byers.

The new deal still needs to be ratified by the Danish parliament while a similar procedure takes place in Canada. Also, negotiations with the EU Commission are pending. As Greenland is part of the so-called Schengen Area in which Europeans can travel freely with principally no border control, the new border on Hans Island will also be considered an EU border towards Canada. It’s possible, though, that the EU Commission in Brussels may accept that no formal border control on Hans Island will be needed.

CORRECTION: In a earlier version of this story, several captions incorrectly identified the countries involved in the 2018 expedition from which the photos originated. The story has been updated to correct that error.