Canada will improve missile defense, Arctic security, says Defense report

Canada plans to sink lots of money into the Arctic—and Nunavut—as the military beefs up and expands surveillance in the region.

The new plan to better defend the Arctic airspace will see surveillance aircraft, remotely piloted systems—commonly referred to as “drones”— and satellites expanding Canada’s joint intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capacity.

This plan will also include a revamp and expansion of the North Warning Sites across Nunavut.

These Arctic defence moves are outlined in a 113-page, recently-released report from the Department of National Defense on Canada’s defense policy, which says “Canada’s renewed focus on the surveillance and control of the Canadian Arctic will be complemented by close collaboration with select Arctic partners, including the United States, Norway and Denmark, to increase surveillance and monitoring of the broader Arctic region.”

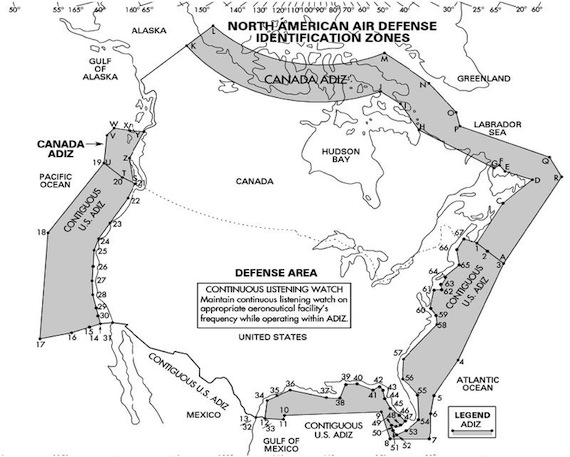

Among new measures: an expansion of the Canadian Air Defense Identification Zone, known as CADIZ, to cover the entire Canadian Arctic archipelago, islands which mainly lie in Nunavut.

This CADIZ enlargement means any aircraft flying in this zone without authorization may be identified as a threat and treated as an enemy aircraft, potentially leading to interception by fighter jets.

The current CADIZ is based on the Distance Early Warning Line radars, which were replaced in the late 1980s by the North Warning System.

“An expanded CADIZ will increase awareness of the air traffic approaching and operating in Canada’s sovereign airspace in the Arctic,” the DND report said.

In the report, the DND points to “unique issues” in the Arctic which include its size and small population, spotty satellite coverage at extreme northern latitudes and technical challenges related to the polar regions.

So the DND says it needs joint intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance solutions that are “specifically tailored to the Arctic environment.”

This will, among other things, require a modernization of the North Warning System, or NWS, which provides aerospace surveillance of Canadian and U.S. northern approaches.

The current NWS is approaching the end of its life expectancy from a technological and functional perspective, the DND said.

And that’s troubling, its report said, because, “unfortunately the range of potential threats to the continent, such as that posed by adversarial cruise missiles and ballistic missiles, has become more complex and increasingly difficult to detect.”

Canada and the U.S. have already launched bilateral collaboration to seek “an innovative technological solution to continental defence challenges including early warning,” the DND said.

Studies are ongoing to determine how best to replace “this important capability,” its report said.

The U.S. and Canada have already said they planned to replace the radar along the North Warning Sites.

But judging from the wording in new DND report, this is will involve some form of ballistic missile defence.

This idea has been around since the early 2000s when Inuit in Canada and Greenland reacted to the U.S. plan for anti-ballistic missile radar and communication systems in several places across the Arctic, including the U.S. Air Force base in Thule, Greenland.

The idea was to defend the U.S. against nuclear missile attacks from so-called “rogue” states such as North Korea and Iraq by missiles launched from ships or land, as well as lasers fired from modified aircraft.

But to make the proposed system work, the U.S. had to put radar and missile sites circling the Arctic.

In 2002, a defense watchdog told Nunatsiaq News that an upgraded Thule air base couldn’t do the job of defending U.S. airspace without assistance from additional sites in Canada.

Then, in 2004, high-level officials from Greenland, Denmark and the U.S. met in the Greenlandic sheep-farming village of Igaliku to sign three deals which would also allow the U.S. to move ahead with its missile defense program.

Since then, radar sites in Alaska and Thule have been upgraded, although the former Liberal government of Paul Martin decided in 2005 that Canada would not join up with the missile defense plan.

The DND also calls for:

• enhancement and expansion of the training and effectiveness of the Canadian Rangers “to improve their functional capabilities within the Canadian Armed Forces;” and,

• joint exercises with Arctic allies and partners.

The new focus on the Arctic, along with the more than 100 other parts of the DND policy, comes with a big price tag.

Annual defence spending is set to increase over the next 10 years from $17.1 billion in 2016-17 to $24.6 billion in 2026-27.

You can find the DND report online here.