What China’s involvement means for Alaska’s latest Arctic gas line plan

Chinese involvement makes the latest Alaska gas line plan different from the rest. But that alone doesn't mean it will succeed.

A decade ago, after a giant Chinese oil company expressed interest in acquiring natural gas from Alaska, Sen. Ted Stevens had a simple answer for Sinopec.

No.

“I will tell the Chinese they have no possible hope of getting gas from us,” Stevens said. “I don’t see it happening. With the shortage of natural gas in the United States, that gas is not going to be allowed to be exported.”

Times change.

The shale gas revolution ended the natural gas shortage in the Lower 48 and the search is on for export markets overseas. Alaska would love to sell gas to Sinopec, a government-owned company with revenues far greater than that of ExxonMobil.

Along with two major Chinese financial institutions, Sinopec is in the early negotiations with a corporation owned by the state of Alaska to try to get a deal.

[A ‘polar silk road’ forms the core of China’s first Arctic policy]

It’s anyone guess if this latest Alaska gas pipeline proposal will fare any better than the dozen proposals that have failed over the past 45 years, but this one is different in two major ways.

First, the $43 billion pipeline project could fit well with China’s declaration that it wants to have a greater say in the future of the Arctic. China has become the second largest importer of liquefied natural gas and it will need additional sources by 2024-2025, when the Alaska project would be in operation.

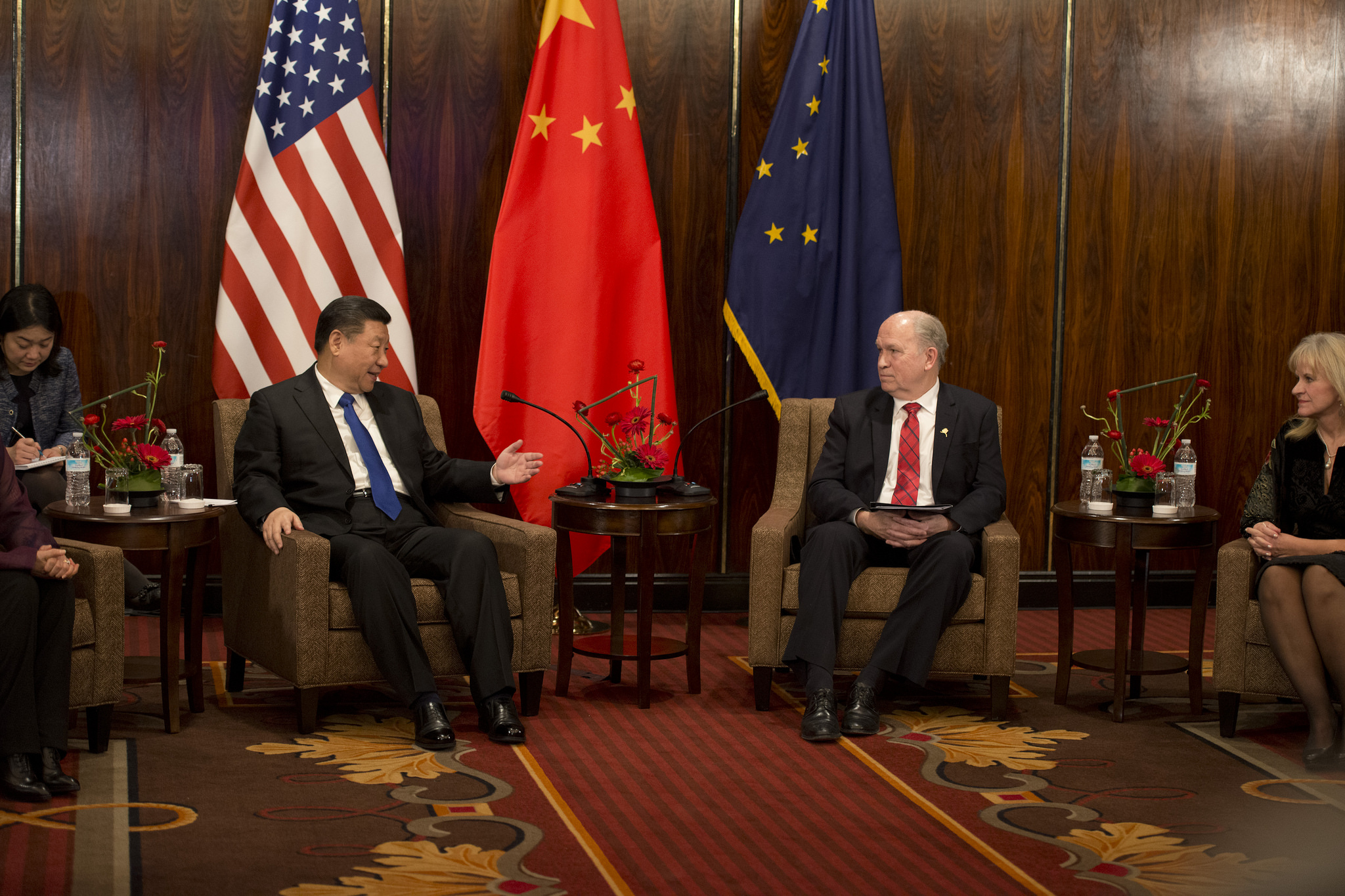

Second, a non-binding agreement about the Alaska project was signed in November in the presence of U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, potentially giving the project the two most important advocates in the world.

But China’s Arctic ambitions and the joint presidential seal of approval do not guarantee that the talks now taking place will end with definitive agreements.

The easiest thing in the world is a non-binding agreement and we’ve had many of those over the years.

The parties said they would like to sign contracts by the end of this year. The current state claim that “the stars are aligned for Alaska LNG” may be another example of wishful thinking.

Gov. Bill Walker, who has made a pipeline the centerpiece of his political life, wants to believe that this time is different. Maybe. But we don’t know that yet.

The high cost of building natural gas facilities in Alaska and the difficulty of getting utilities and other users to sign long-term contracts are issues that have and will knock the stars out of alignment whenever markets or political whims shift.

In one sense, the “Polar Silk Road” initiative and the involvement of national leaders have complicated the politics and economics of a development project that has remained an impossible dream for two generations of Alaska leaders — tapping the immense natural gas reserves on Alaska’s northern coast.

Though it is far from the Arctic Circle, China has declared itself a “Near-Arctic State” and looked to expand its northern reach with ventures in Norway, Iceland and Greenland, and a $12 billion investment in the Yamal liquefied natural gas plant on the north coast of Russia. There is every reason to believe that the Chinese investment — which helped offset U.S. sanctions against Russia — made the difference in the Yamal project, which went into operation late last year on schedule.

Granted “observer” status with the Arctic Council five years ago, China released a white paper on Arctic policy in January that highlighted concepts like cooperation, coordination and opportunity.

A major energy investment in Alaska could fit into that strategy, a consultant told the Alaska Legislature in February, especially because investments in Canada have not fared well.

The policy paper called for strengthening “technological innovation, environmental protection, resource utilization, and development of shipping routes in the Arctic,” a broad statement that has raised hopes in Alaska.

For decades, the internal economics and politics of the major oil companies in Alaska led to numerous pipeline projects that began with great fanfare and then faltered.

Now the internal and external politics of China and the U.S. have assumed a much larger role in settling the pipeline’s fate. I don’t know which is more transparent.

It’s always possible that an Alaska project could become collateral damage in a broader fight between the two countries.

The pipeline has always required what the oil companies like to call “fiscal certainty,” meaning that they will know the tax rate over the life of the project.

That will remain a potential political sticking point in Alaska with Chinese involvement.

The Trump administration is chaotic, reflecting the mental state of the man at the top. While the president has claimed he has a “great relationship” with President Xi, on Thursday he announced what could be the opening shot in a trade war, calling for a 25 percent tariff on imported steel and 10 percent on aluminum. This could lead to retaliation against the U.S., hardly the stable foundation the Alaska project requires. Trump’s presence at the signing ceremony in November could be irrelevant.

Meanwhile, President Xi has moved to strengthen his authoritarian rule and extend his ability to remain in office, which will make relations with the U.S. more uncertain and confrontational in the years ahead.

For Alaska, getting the gas line project moving quickly is important for political and financial reasons, which gives the potential investors, who don’t face that same time pressure, a significant strategic advantage in negotiations.

The power to proceed or not with an Alaska project has never been more subject to centralized government control, but until we see what agreements, if any, are produced we won’t know if this pipeline project is real and what Alaska would be asked to give up in exchange.

Asked to offer advice to the Alaska Legislature on the Chinese connection, Alberta consultant Wenran Jiang said there is a potential market for Alaska gas and China has been innovative in developing big projects.

Perhaps the most important thing he said was that Alaska should expect hard negotiations.

“I know they’re very tough, not easy, you can expect that,” he said.

While it is certainly possible that everything will fall into place this time around and Alaskans will celebrate the results, if history has taught us anything about the gas pipeline, it’s always been easier said than done.

Dermot Cole lives in Fairbanks, Alaska. A veteran newspaper columnist and author, he can be reached at de*********@gm***.com.