Chinese-linked Australian mining company sues Greenland for $11bn over lost revenue

The US, China and the EU are all likely to watch closely as a battle over one of the world’s largest deposits of rare earths is taken to court. Australian-owned Greenland Minerals A/S wants a mining license, or compensation of up to $11.5 billion for lost revenue.

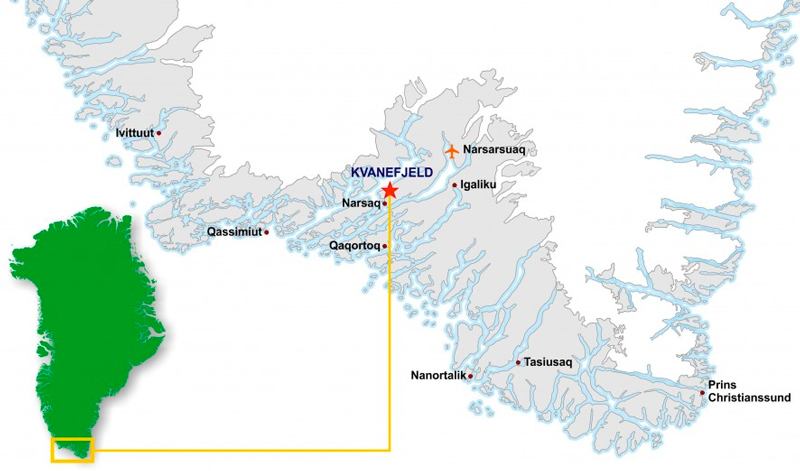

One of the world’s largest deposits of rare earth minerals is located in the Kuannersiut mountain in southern Greenland. The deposit has long been coveted by the US, China and the EU, but instead of being mined and brought to world markets, the valuable minerals are now subject to a bitter court case between the China-linked Australian mining company and the Greenlandic government.

In 2021, the government in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, passed legislation to ban uranium mining in Greenland, and this summer Greenland Minerals was refused a mining license for its Kvanefjeld project at Kuannersuit mountain. The rare earths in the area are commingled with uranium, and mining would inevitably bring the latter to the surface, a result the Greenland’s government is determined to prevent.

Legal offensive

Greenland Minerals, a subsidiary of Perth-based Energy Transition Minerals, has now mounted a counter-offensive.

The company has been engaged in exploration at the Kuannersuit mountain since 2007. In July it filed a 517-page Statement of Claims with the Arbitral Tribunal in Copenhagen. The statement includes a claim for a license to mine or, should that fail, a claim for compensation as well as an estimate of the company’s loss of investments and future earnings that could total $11.5 billion, a potentially crippling sum for Greenland.

Strong US interest

Observers in many countries are likely to follow the proceedings. Greenland is still part of the Kingdom of Denmark and the US, through its embassy in Denmark, has been keenly interested in Greenland’s rare earths for decades.

Carla Sands, a former US ambassador to Denmark, held talks with Greenland Minerals in southern Greenland not long before then-US president Donald Trump in 2019 suggested buying the country from Denmark.

The EU has also long expressed interest. However, China may be in pole position for access. Chinese mining corporation Shenge Resources owns 9% of Greenland Minerals and is represented on its board. Greenland Minerals has long been banking on financial and technical support from Shenge for the establishment of the proposed Kuannersuit mine.

On a visit to Copenhagen in late September, Greenland Minerals commercial manager Garry Frere told Arctic Today that Shenge “will support the project without a shadow of a doubt”.

The Chinese connection makes the Kuannersuit project controversial. China controls some 90% of the world’s supply of rare-earth minerals — essential for a host of green technologies such as batteries for electrical cars and wind turbines, as well as for the defence industry, which uses them in missiles, fighter jets and other equipment.

“Not a threat”

The high loss estimates by Greenland Minerals could easily exhaust Greenland’s economy, should compensation be awarded to Greenland Minerals. Even so, the company denies any wish to intimidate the Arctic country of 57,000.

“It is not a threat,” said Frere, even if he understands that others may interpret the suit that way.

“I don’t think the government or its advisors expected what they saw in our statement of claim that we lodged in July. I think that document might have come with quite a bit of surprise,” Frere said.

“It might be that when the detail of the argument we are making is properly understood by Kammeradvokaten (the government’s legal council, ed.) and the government, they will form a view that Greenland Minerals has quite a substantial argument. We might not win, but there is certainly no guarantee,” he said.

He speculated that the government in Nuuk will soon begin to weigh the potential cost of paying damages to Greenland Mineral against the possible gains from a mine at Kuannersuit. Greenland Minerals argues that Greenland would likely earn more than $20 billion in taxes and royalties on minerals over the expected 37-year life of the mine if Greenland Minerals was allowed to proceed at Kuannersuit.

Financing the case

The trial will likely be very expensive for both parties, but Frere claims that Greenland Minerals has resources to carry on for as long as it takes. According to him, Burford Capital, US-based specialists in funding legal cases, has made capital available that could make the case less painful for Greenland Minerals.

“We call it non-recourse. If we lose the arbitration, they get none of their money back. If we are successful they get a fee based on how much they have spent and they get a share of the reward. This is not unusual for small businesses like ours,” Frere said. He declined to state how large a share of the potential wins Burford Capital is entitled to.

Greenland Minerals has engaged Clifford Chance, one of the UK’s largest law firms with offices across the globe, and a reputed Danish law firm to do the legal work and handle court appearances.

Breach of contract

After a stopover in Copenhagen, Frere was set to travel to Nuuk, and he seemed unusually knowledgable about Greenland’s domestic politics.

Strong forces within Siumut, one of the two parties in Greenland’s governing coalition, want to unravel the ban on uranium mining. Frere believes that there might be a new chance for the Kuannersuit mine after a planned general election in Greenland in April of 2025.

In a 2011 add-on to Greenland Minerals’ license to explore for minerals at Kuannersuit, the Greenlandic authorities stipulated that any potential requests by the company to exploit the Kuannersuit vein could be rejected by Nuuk for purely political reasons.

The project at Kuannersuit has from the beginning been highly controversial in Greenland. The fear that mining could contaminate the nearby town of Narsaq and its surroundings runs deep, and the 2011 political clause to Greenland Minerals’ exploration license mirrored a deep split in the Greenland populace regarding the project.

Even so, Frere and Greenland Minerals maintain that the government in Nuuk is in breach of contract. The company argues that the 2011 clause has been rendered invalid since numerous other positive signals and acts by the authorities in Nuuk have made Greenland Minerals predict that in the end — despite the 2011-clause — it would receive a license to mine.

In the company’s July Statement of Claims several messages to Greenland Minerals from the authorities in Nuuk and excerpts from Greenland’s political discourse were presented. From 2014, when a previous partial ban on uranium was lifted, Greenland prepared for uranium exports and Nuuk signed on to several international uranium conventions. Greenland Minerals interpreted the combined words and deeds as binding. Frere argues that matters have not been dealt with properly by Greenlandic authorities in this process.

“We have spent 13-14 years following a certain set of rules with an expectation that if we did the right thing, produced the right pieces of paper and did the right work we would then be issued a license,” said Frere.

Greenland has less than 60,000 inhabitants and a limited economy, but Frere has no qualms raising claims that might badly hurt its economy,

“While Greenland is a small country, it is part of the Kingdom of Denmark and it chooses to encourage people to come and potentially exploit its mineral resources. By doing that you take away your right to say ‘oh, no, we are a poor country, you are a big international “ruly” boy and you have come to impose.’ We were invited, we followed the rules, we met all the requirements that were put in front of us, but at the last minute the goalposts were moved,” he said.

The minister

In Greenland funding for the court case has been allocated by parliament and on the phone from Nuuk, Greenland’s naalakkersuisoq (minister) for raw materials, Naaja Nathanielsen, expresses no desire for compromise.

“The company says that because they feel that they have received a signal this must overrule the terms that are spelled out in their license. We argue that all sorts of things might have been said politically, but that this means nothing if the terms are not changed. There can be no tampering with any given government’s right to determine terms and legislation about how the resources of its country are to be utilized. This is an important principle for us and we will follow it through to the end,” Nathanielsen said.

Greenland Minerals also argue that the ban on uranium cannot be applied to the Kuannersuit project as this would deny the company rights to which it is entitled to by Greenland’s own laws. Nathianielsen also rejects this claim.

“The company does not read the uranium law correctly. The law applies to future licenses. If Greenland Minerals had been issued with a license to extract minerals before the law on uranium came into effect, they might perhaps have been right, but they had not,” she said.

Will the offensive work?

The question remains whether fear of an expensive court case and potentially debilitating payment of damages will stir public opinion in Greenland and influence the Greenlandic government.

Mariane Paviasen, chair of Greenland’s parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs and Security, says she doesn’t fear that scenario.

“They do not scare me. This only shows once again that the company does not care at all about our society,” she said.

Paviasen is a former central figure of Urani Naamik (No to Uranium), a non-governmental organization which has spearheaded opposition to the mining project at Kuanersuit. She and other opponents maintain that Greenland Minerals conducted its business in the country in less than savory ways. Its lobbying has included hiring leading Greenlandic politicians and former high ranking public officials to further its case.

Nathanielsen said that she is convinced that Greenland has the better legal case. She recognizes though that Greenland Minerals campaign is having an effect.

“I regard it as a maneuver to create uncertainty and to target politicians, and it has worked extremely well as clickbait. A lot of journalists have reacted. I just think it is more interesting what the company is basing its case on,” she said.

Greenland’s government has until early January 2024 to react to Greenland Minerals’ Statement of Claim.

The government argues that the Arbitral Tribunal in Denmark does not have powers to handle complaints against political decisions made by the government of Greenland. Instead, the government argues, Greenland Minerals may bring their case before the courts in Greenland.

Should Greenland Minerals be awarded compensation for the losses it claims, the sums involved might exceed Greenland’s ability to pay. Greenland Minerals argues, however, that the Danish government could also be made responsible. Until 2009, the two countries shared the responsibility for Greenland’s mineral deposits.