Climate change could enable Alaska to grow more of its own food

Now is the time to plan for it.

Gardeners in Alaska know that it’s hard to grow big, juicy tomatoes here. But as the climate rapidly warms in the far North, that could change.

Anchorage reached 90 degrees Fahrenheit (32 degrees Celsius) for the first time on record in 2019. Arctic sea ice is rapidly receding, and average annual temperatures are 3 to 4 degrees Fahrenheit higher statewide (1.7 to 2.2 degrees Celsius) compared with those in the mid-20th century.

These climate shifts are triggering immense challenges, such as structural collapses as long-frozen ground thaws and risks to life and property from increasing wildfires. Agriculture is one area in which climate change may actually bring some benefit to our state, but not without stumbling blocks and uncertainties.

As a climate researcher at the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, I recently worked with other scholars, farmers and gardeners to begin investigating our state’s agricultural future. We used global climate change models downscaled to the local level, coupled with insights from farmers growing vegetables for local markets and tribal groups interested in gardening and food security. Our goal was to take a preliminary look at what climate change might mean for agriculture in communities across the state, from Nome to Juneau and from Utqiaġvik to Unalaska.

Our research suggests that planning for future decades and even future generations may be crucial for keeping Alaska fed, healthy and economically stable. We have created online tools to help Alaskans start thinking about the possibilities.

Farming in a cold climate

Alaska’s vast size is reflected in its wide range of climate zones, from the temperate and rainy Tongass National Forest to the rapidly greening but still frigid Arctic tundra. In ocean-moderated Anchorage, the first fall frost doesn’t typically arrive until late September, but historically, average July temperatures were a modest 59 degrees F (15 degrees C). Even that is warm compared with 56 degrees F (13 degrees C) for Juneau and 51 degrees F (11 degrees C) for Nome. Here in Fairbanks, July is a little more summery, but frost often strikes in August, and winter temperatures regularly drop to minus 40 degrees F (minus 40 degrees C).

With cool summers, short growing seasons and frigid winters, most farming in Alaska has long been limited by the state’s cold climate. Although home gardens are popular, with growers favoring hardy crops such as cabbages, potatoes and carrots, agriculture is a tiny industry. Recent data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture tallies a mere 541 acres of potatoes, 1,018 acres of vegetables and 22 acres of orchards in our 393 million-acre state.

View this post on Instagram

Crops of the future

Our climate modeling suggests a dramatically changing future for Alaska crops by 2100, with frost-free seasons extending not just by days, but by weeks or months; cumulative summer heat doubling or more; and the coldest winter days becoming 10 or 15 degrees less extreme.

Perhaps the most startling projected shift is in what is known as “growing degree days” — a measurement of the cumulative buildup of daily heat above a crop-specific minimum threshold, across an entire summer.

For example, barley is a cold-hardy species that can start sprouting at temperatures as low as 32 degrees F, but the speed of its growth nonetheless depends on warmth. If the average temperature on a given day is 50 degrees F, 18 degrees above barley’s threshold, that day counts as 18 growing degree days; a 60-degree day would count as 28. Barley won’t reach maturity until it experiences a total of about 2,500 growing degree days above 32 degrees F — a target that could be reached in about 138 days at 50 degrees F, or 89 days at 60 degrees F.

The math changes for other thresholds. Broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage and Indiana wheat won’t grow unless temperatures exceed about 40 F. “Warm” crops such as corn and tomatoes are even fussier, with a threshold of 50 F; for these plants, a 60-degree day represents only 10 growing degree days. Such crops have been almost entirely out of reach for Alaskans except in greenhouses.

In the past, I would have been able to expect only about 850 growing degree days above a 50 degrees F threshold here in Fairbanks over the course of a typical summer, nowhere near the roughly 1,500 that corn would require to produce mature ears. But by the year 2100, my grandchildren might anticipate 2,700 growing degree days each year above a 50 degrees F threshold — more than enough to harvest sorghum, soybeans, cucumbers, sweet corn and tomatoes.

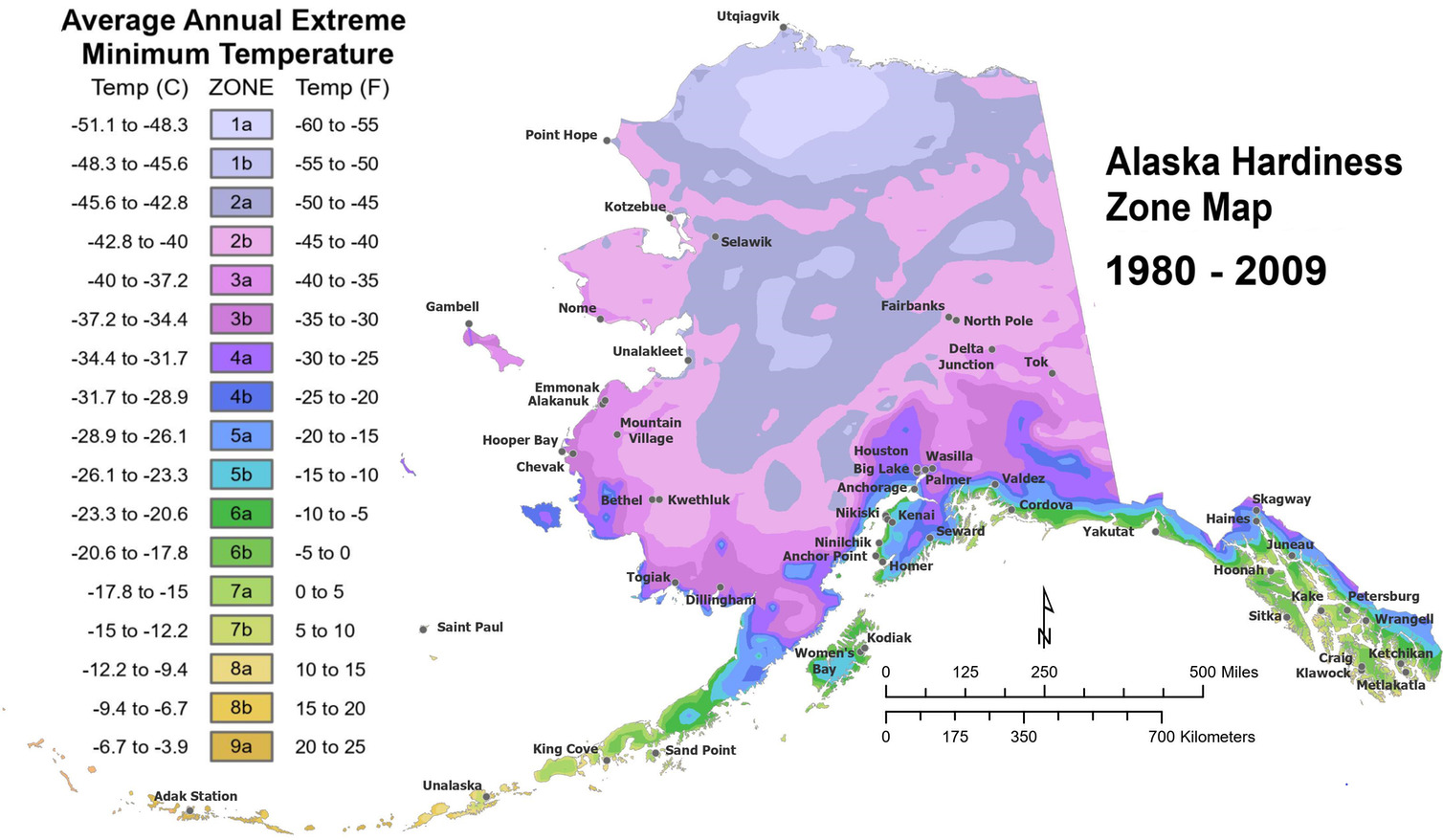

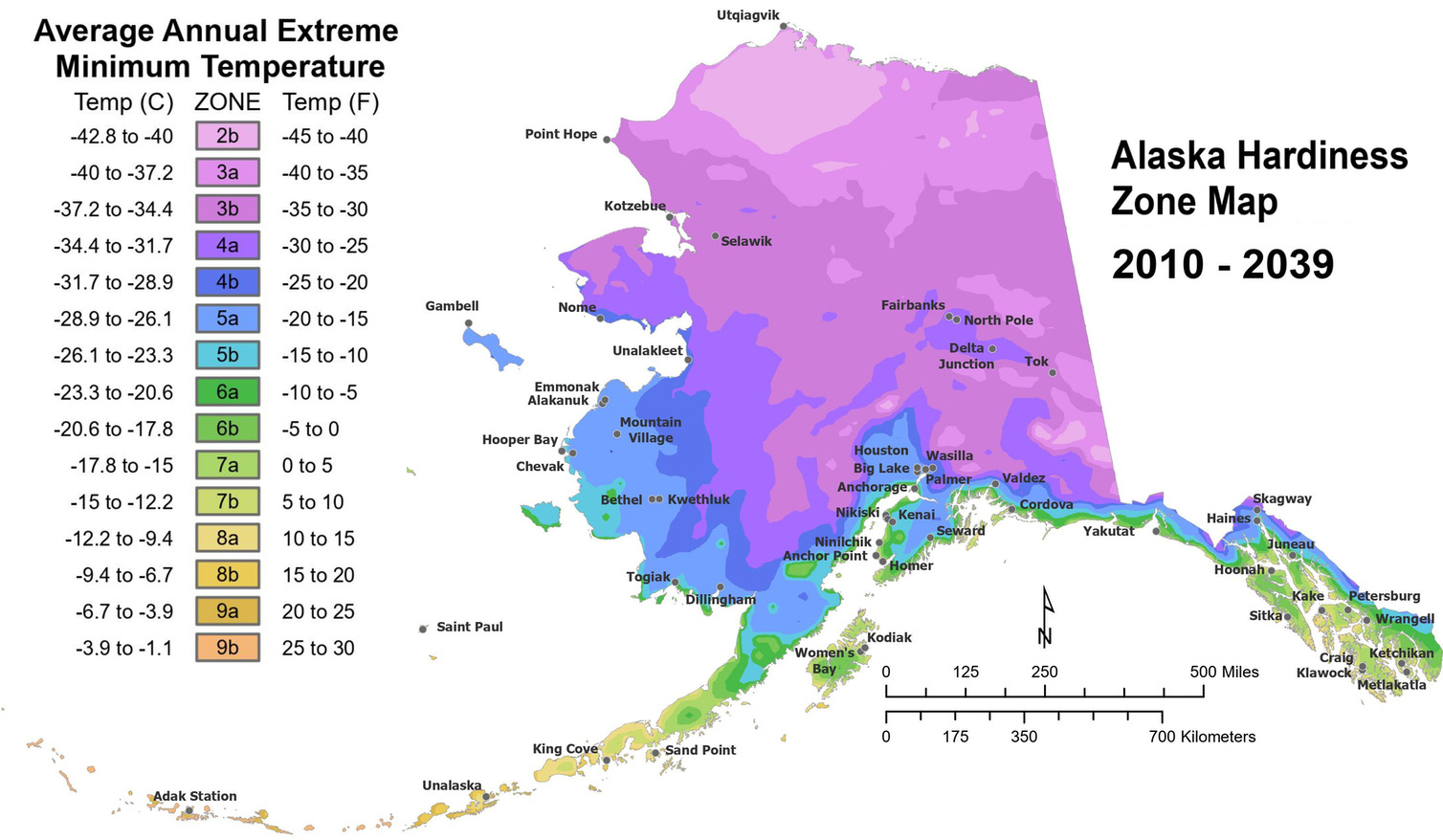

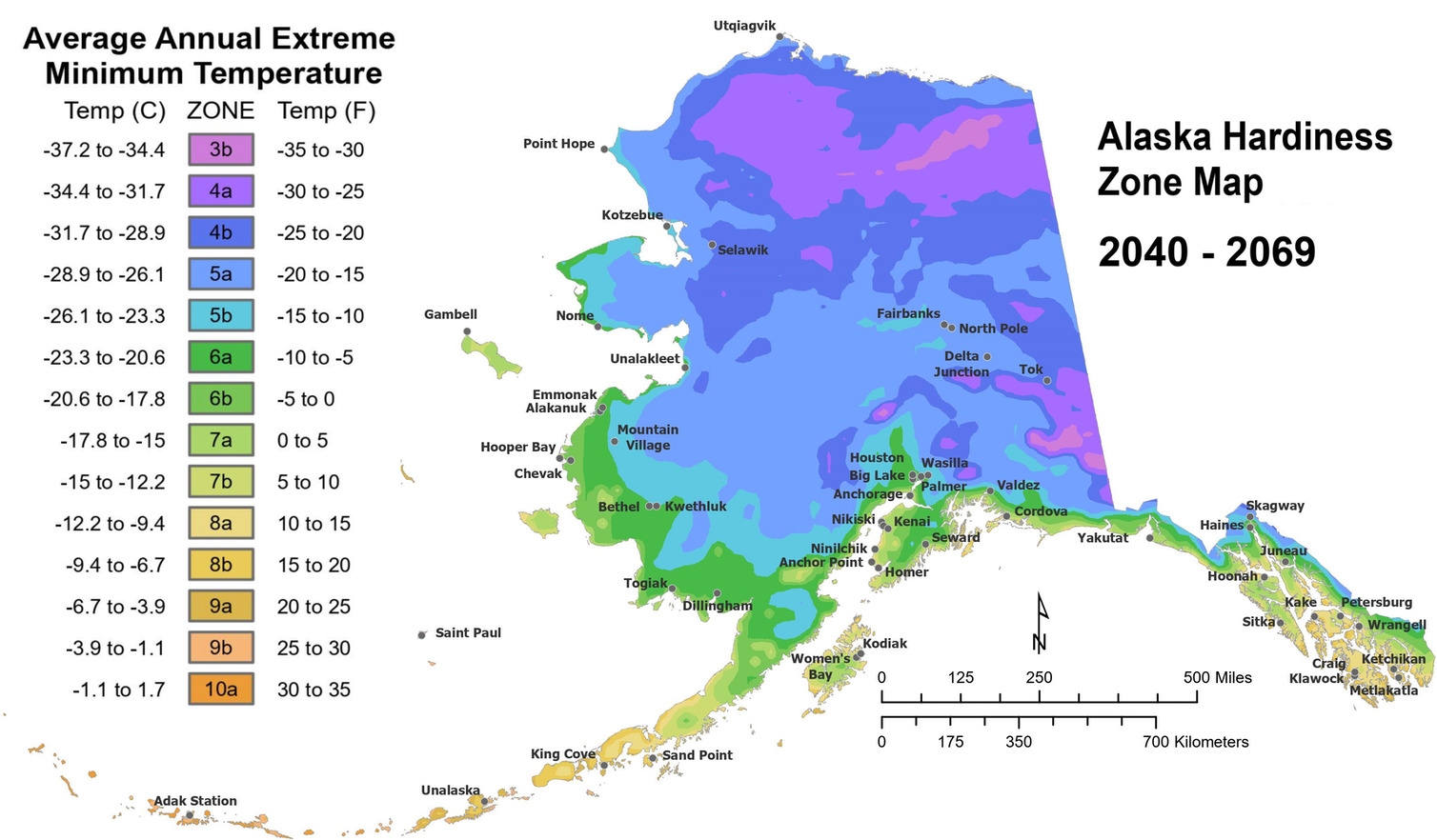

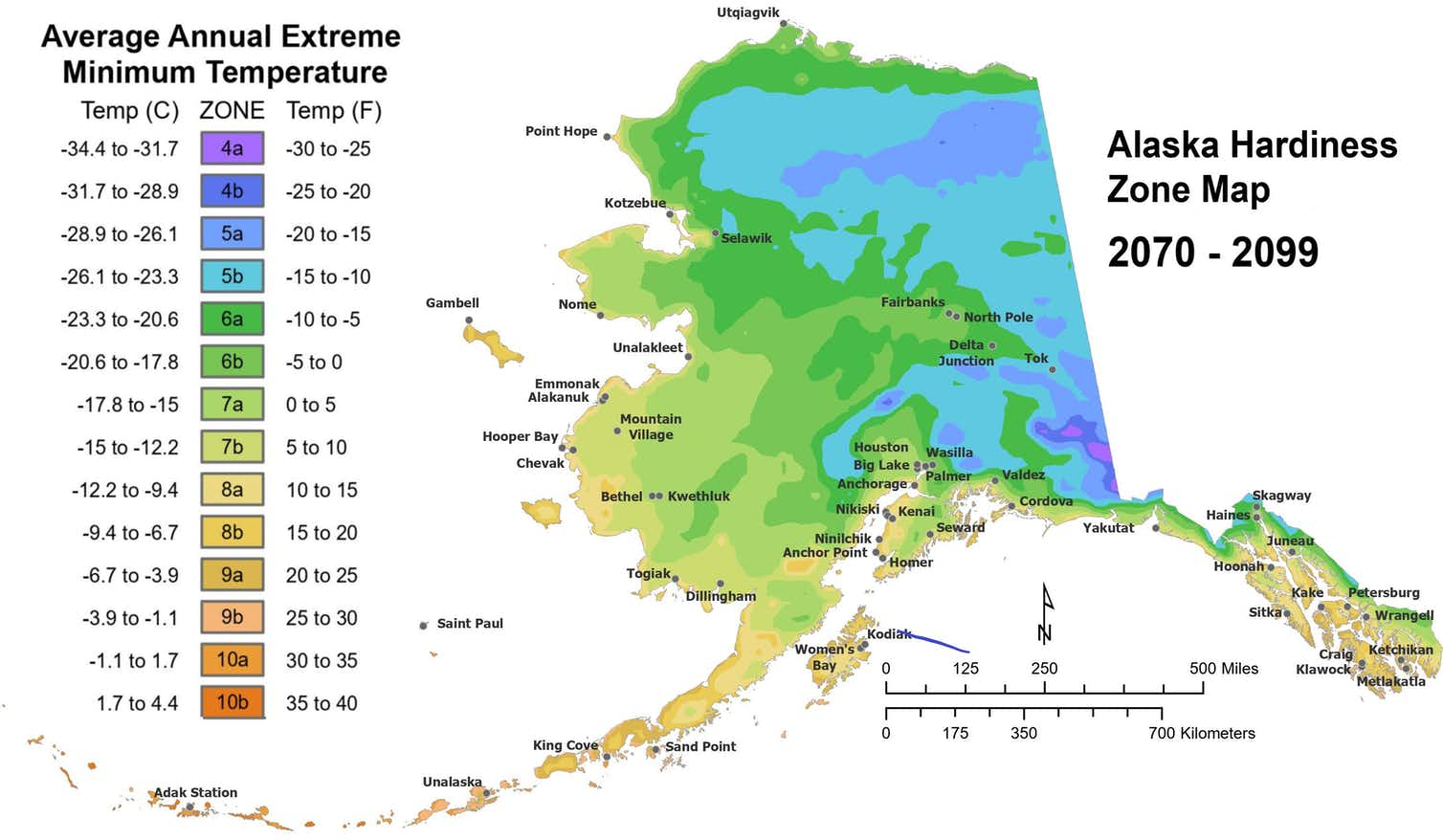

We’re also likely to see huge changes in potential perennial crops because of our loss of winter chill. Many gardeners are familiar with USDA Plant Hardiness Zones, which are based on the average coldest winter temperature for a given area. Using the same categories as the USDA, we projected Alaska Hardiness Zones.

Dramatic shifts in these maps provide a snapshot of just how profound climate change is in the far north. Historically, my Fairbanks home is in Zone 1 or 2. By the end of the century, it is projected to be in Zone 6 — the current zone in such places as Kansas and Kentucky.

Food security and supply chains

Only 5 percent of the food we consume in Alaska is grown or raised here. Shipments from the Lower 48 travel vast distances to reach our state and its dispersed communities. Alaskans are vulnerable to supply chain disruptions when even a single barge fails to arrive or one road is blocked.

Growing more fresh foods here would help Alaska economically and nutritionally — but it won’t happen automatically. To achieve meaningful long-term increases in agriculture, the Alaska Food Policy Council has recommended creating a proactive state-funded nutrition education program, developing more food storage infrastructure, offering financial incentives for expanding agriculture and teaching residents about northern growing methods. The council’s research suggests that the state could realize major benefits from investments in training, technology, support for clustered businesses such as packaging and storage, and programs to foster a farming culture.

So food prices can easily be double or more that in temperate or warmer zones. There’s only like 6 Walmarts in Alaska, 4 being in/around Anchorage. Even if you don’t shop there, it illustrates how scarce grocery stores are. There are 145 just in Alabama.

— ᏖᏗ Tedi 🪶 BLM Land Back 🌹 (@teditsodani) August 8, 2018

A tool for gardeners and farmers

To make the results of our modeling available to home gardeners and rural villages, we created an online tool, the Alaska Garden Helper, and a fact sheet. Alaskans can select their community, decide which of the above questions to explore, and choose what temperature thresholds are of interest, from “hard frost” (28 degrees F or minus 2 degrees C) to “warm crops” (50 degrees F or 10 degrees C).

The tool includes brief explanations of unfamiliar concepts such as growing degree days. It also includes lists of potential crops such as barley, beans, cabbages and corn, each with minimum values gleaned from published literature, for the summer season length and growing degree days necessary for that crop to successfully mature.

Nancy Fresco is SNAP coordinator and research faculty at University of Alaska Fairbanks.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.