Climate change thaws world’s northernmost research station

At Ny-Ålesund, on Norway's Svalbard archipelago, data is getting harder for scientists to collect — and sometimes disappearing before it can be collected.

NY-ÅLESUND, Norway — At the world’s northernmost year-round research station, scientists are racing to understand how the fastest-warming place on Earth is changing — and what those changes may mean for the planet’s future.

But around the tiny town of Ny-Ålesund, high above the Arctic circle on Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, scientific data is getting harder to access. And sometimes it’s vanishing before scientists can collect it.

Scientists hoping to harvest ice cores are finding glaciers inundated by water. Research sites are getting harder to reach, as earlier springtime melt leaves the ground too barren for snowmobile travel.

Researchers have been studying the polar region for decades — with Ny-Ålesund’s weather records going back more than 40 years. But their work has become vitally important as climate change ramps up. That’s because what happens in the Arctic can impact global sea levels, storms in North America and Europe, and other factors far beyond the frozen region.

While the Arctic is warming about four times faster than the rest of the world, in Svalbard temperatures are climbing even faster — up to seven times the global average.

Last summer was the hottest on record. August temperatures in Ny-Ålesund were on average 5.1 degrees Celsius degrees, about 0.5 degrees C warmer than normal for the month.

Polar bears — left hungrier due partly to the loss of sea ice, their hunting grounds — are more often seen prowling nearby islands in search of food.

Jean-Charles Gallet, a glaciologist with the Norwegian Polar Institute who has been coming to Ny-Ålesund for about 12 years, said that, whereas scientists could once travel into June, they cannot plan fieldwork after mid-May now.

“The snow in the valley is gone, and you are stuck in town, and your snowmobile is in the garage.”

The weather around Ny-Ålesund has become wilder. A few decades ago, snow typically began falling in October, while February and March were the year’s coldest and calmest months. Not anymore.

This winter saw snowfall only from January, with storms intensifying the next month. “We’re on storm No. 9 since early February. Wow. I’ve never seen that,” Gallet said in his office this month, as rain drizzled from a gray sky. “Even today, we are in early April, and it rains.”

Life at 79 degrees North

Established as a mining settlement in 1916, Ny-Ålesund became a hotspot for international researchers after several deadly mining accidents shuttered operations in the 1960s.

Norway was granted sovereignty over Svalbard during the Versailles negotiations at the end of World War I. This arrangement allows citizens from any of the 46 countries that have signed the treaty to reside in the archipelago.

The European Space Research Organization (ESRO) put up a ground station in 1967 to help track orbiting satellites. Geologists and geophysicists also began setting up field camps around Kongsfjord, the large fjord that borders Ny-Ålesund.

Today, 11 countries, including China and India, have a presence in Ny-Ålesund. But the town has only about 35 year-round residents.

Daily life centers around the town’s diversions — a sauna, a sled dog yard, and a weekly nighttime gathering called “Strikk og Drikk,” or “Knit and Sip,” during which residents stitch sweaters over a glass of wine.

In summer, Ny-Ålesund’s population swells to more than 100 as scientists fly in from across the world. They gather in the glass-fronted canteen overlooking Kongsfjord, where a taxidermied polar bear presides over meals.

“One of the special things about this place is there are a lot of different scientists. I’m a chemist. There are biologists, geologists,” said visiting researcher Francois Burgay of the Paul Scherrer Institute in Switzerland. “It’s one of the few places in the world where these kinds of exchanges are so informal and so spontaneous.”

That cross-disciplinary collaboration is important for climate research. Svalbard is warming faster than almost anywhere else in the Arctic and cooperation can be critical for understanding how climate impacts will ripple through the polar ecosystem, from ocean to atmosphere, plants to animals.

But even Ny-Ålesund itself is unstable. Last year, Kings Bay AS, the state-owned company that manages the town, closed a laboratory where scientists processed samples from fish, snow and ice. Thawing permafrost had cracked its foundation.

Four buildings damaged by thawing permafrost have seen repairs over the past decade, Kings Bay AS operations manager Espen Blix told Reuters, including the town store, which contractors are fixing this year on a budget of 6.9 million Norwegian kroner ($658,000). Another five are in need of repairs.

Still intact are the town’s sauna and jacuzzi, giving residents a chance to relax.

“The dark season is really nice,” said town safety instructor Christer Amundsen, who has lived in Ny-Ålesund full-time since 2019, referring to the October to February period when the sun never crests the horizon, bright stars fill the sky and blue-green auroras shimmer over the settlement.

Chasing ice

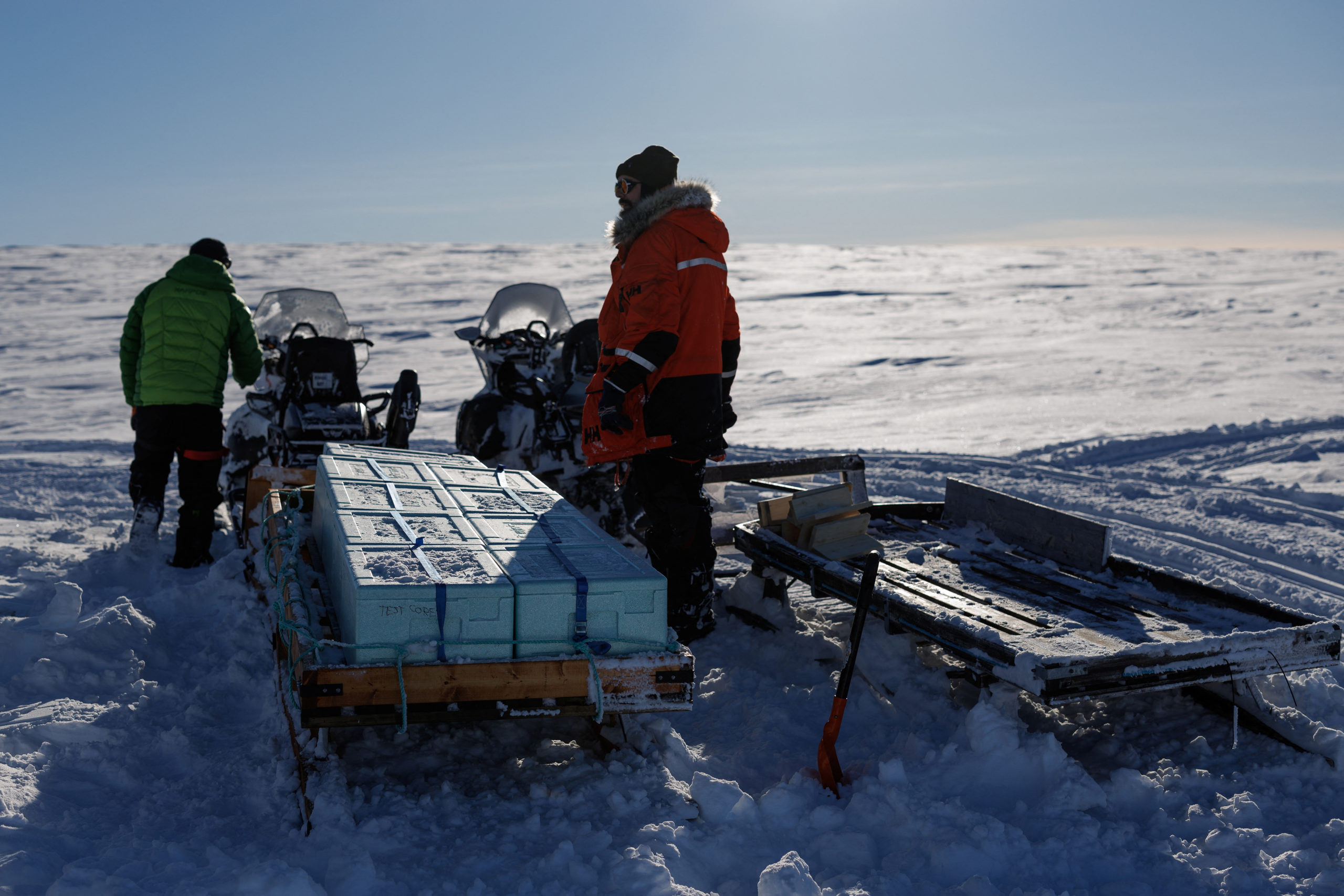

Bracing against wind gusts up to 15 meters per second (34 miles per hour), a team of scientists pitched camp this month on the Holtedahlfonna icefield, a 3-hour snowmobile drive from Ny-Ålesund riven with dangerous crevasses.

The team hoped to drill 125 meters into Dovrebreen glacier, hoping to collect two ice cores for studying 300 years of climate records — part of an effort by the non-profit Ice Memory Foundation to collect and preserve ice cores from melting glaciers around the world.

“We must drill now because we might not have time in the future to do it again,” said expedition leader Andrea Spolaor, a geochemist with the Italian National Research Council.

Dovrebreen glacier, which feeds the icefield, was chosen partly because of its high elevation, 1,100 meters (3,600 feet) above sea level, where temperatures are cooler. That boosted the chance of finding good cores with the ice still intact.

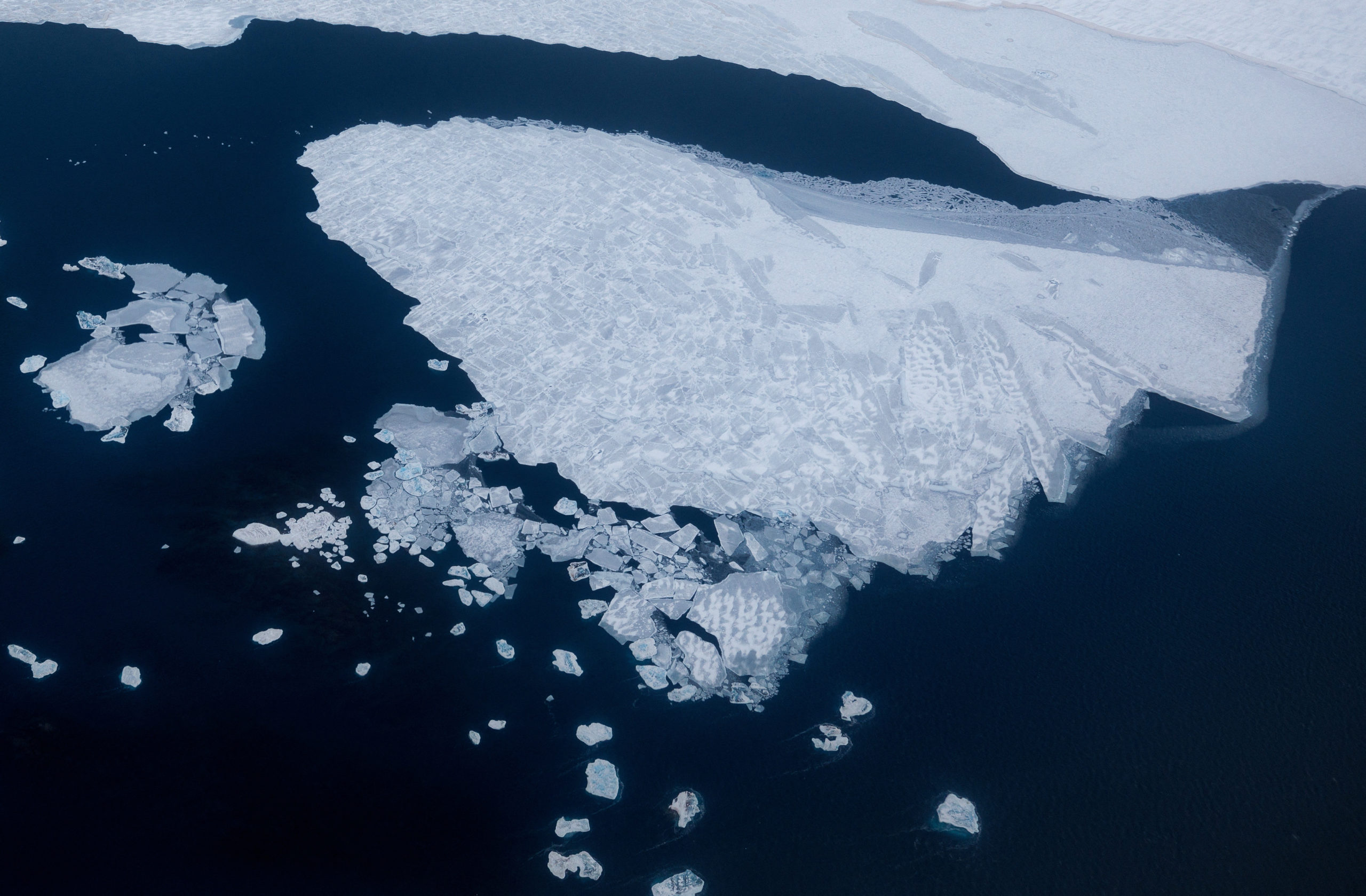

They were shocked when the drill, at only 25 meters deep, suddenly sloshed into a massive pool of water. “We did not expect such a huge water flux coming out from the glacier, and this is a clear sign of what is happening in this region,” Spolaor said. “The glacier is suffering.”

When scientists last drilled at the Dovrebreen site in 2005, the area was completely frozen.

Paleoclimatologist Carlo Barbante, vice chairman of the Ice Memory Foundation, said melting ice can distort the evidence in glaciers from years past: “It’s like putting water on a book and having all the ink diluted so you can’t read what is written.”

The water meant the team could only gather one incomplete ice core from 52 meters down. After nearly two weeks of operation, and two drill motors broken by the aquifer, Spolaor and his team decided to move their site some 150 meters southwest and to a slightly higher elevation, where they ultimately collected 3 ice cores from 73 meters down.

Bears around town

On a snowfield a kilometer south of Ny-Ålesund, the chemist Burgay filled plastic test tubes with snow, looking for chemical signals from marine algae blooms which travel from the ocean to the atmosphere and are deposited with the snow.

Once these signals are identified, he hopes scientists will be able to use them to understand how Arctic waters have changed in the past, and project how they might change in the future.

But even collecting such data is becoming riskier as polar bears roam nearby.

“In winter, you don’t see anything,” said Burgay. “Just the light from your headlamp, maybe the eyes of the reindeer, and some footprints in the snow.”

Eight watchmen take turns patrolling the perimeter of Ny-Ålesund for polar bears — scaring away approaching bruins.

The idea is to “try to avoid it getting to the center of Ny-Ålesund,” said Jakob Weiset, a polar bear guard who pulls double-duty as the town plumber.

Last summer, bears were spotted near town on 13 occasions, he said.

Polar bear sightings in Kongsfjord over the past four years “have been higher than ever before,” said Maarten Loonen, a migratory bird biologist with the Arctic Centre of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands who has been coming to Ny-Ålesund every summer since 1990.

Resting harbour seals alongside nesting seabird colonies are drawing the hungry carnivores closer, said Joanna Sulich, a biologist with conservation nonprofit Polar Bears International.

“For many researchers who are studying those birds, it’s something of concern,” Sulich said.

She’s helping Kings Bay AS design safety brochures for Ny-Ålesund scientists, who must undergo training to learn how to act around polar bears. Scientists are also taken to a shooting range to practice using a rifle, a must-have when traveling outside of town.

“If you work along the coast long enough, even taking all the precautions, you’re likely to eventually see a polar bear,” Sulich said. “Your training and understanding of behavior is essential.”

This article has been fact-checked by Arctic Today and Polar Research and Policy Initiative, with the support of the EMIF managed by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Disclaimer: The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the author(s) and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.