Climate-driven changes in the Arctic are interconnected, says 2020 annual report card

Big changes caused by climate change in the Arctic are linked to one another, NOAA's annual snapshot says.

The Arctic continued a streak of record or near-record climate events over the past year — racking up the second-highest average air temperatures in a century-long history, the second-lowest sea-ice minimum, a record heatwave in Siberia, warm sea-surface temperatures and other disruptions, said an annual report issued Tuesday.

The lesson of the 15th annual Arctic Report Card, a wide-ranging assessment overseen by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration that was released Tuesday, is the “interconnectedness of it all,” said Rick Thoman, one of the report’s main editors.

“All this stuff — the ocean, the atmosphere, the biological, terrestrial activity — all of it is interconnected,” said Thoman, a climate scientist with the Alaska Center for Climate Assessment and Policy at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

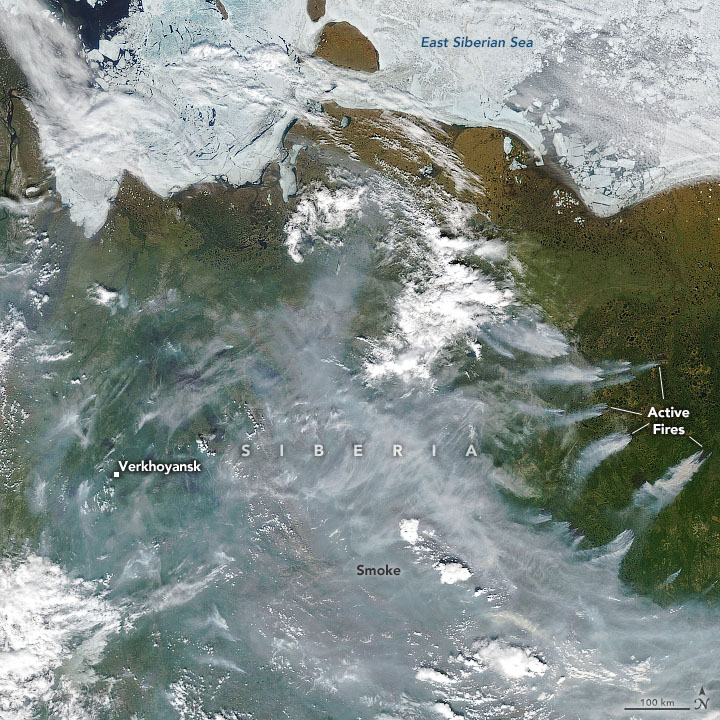

The Siberian heatwave of the past year is a prime example of that, he said. Warm waters in winter led to an early melt of ice in the sea and snow on land, which led to cascading effect like the massive wildfires, he said. “The Siberian wildfires didn’t occur in isolation,” he said.

The 2020 Arctic Report Card was issued at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, which is being held online this year because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The dramatic Arctic changes impact the rest of the world, the report card said. These are effects that were not fully understood when the first Arctic Report Card came out in 2006, the 2020 report said.

Researchers who wrote the first report card, for example, “were just beginning to see signals of rapid changes in the Greenland Ice Sheet,” the new report says. Now they know that the Greenland Ice Sheet is losing mass at nearly quadruple the rate at the start of the 21st century and that it is the biggest contributor to global sea-level rise, adding 0.7 millimeters per year, the report card says.

Greenland and the melting glaciers and ice caps elsewhere in the Arctic, which are adding another 0.4 millimeters a year, are the top contributors to global sea-level rise, outpacing Antarctica for now, the report card said. Alaska glaciers in particular were important contributors, with a record mass loss measured in 2019, the year with the most recent available data.

That rise is “already acutely felt by coastal communities during storms, storm surges and high tides.”

But it is the rest of the world’s carbon emissions that are the root cause of Arctic accelerated warming and the cascading effects, scientists who compiled the 2020 report card stressed in an online news conference hosted by AGU on Tuesday.

And because Arctic thaw and melt in the Arctic feeds into a system of positive reinforcement, Arctic warming will continue to outpace the global rate for decades, Jim Overland, an oceanographer with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Research Laboratory and a co-author of the Arctic Report Card, said in the news conference.

“While we may be able to hold the globe down to a 2-degree increase, the Arctic will be more like 4 or 5 degrees warming before midcentury,” Overland said, referring to a 2-degree Celsius target set in the 2015 Paris climate agreement. “That’s pretty much locked in. What we do now will greatly impact what happens in the second half of the century.”

Some highlights of this year’s report card:

– The average Arctic air temperature from October 2019 to September 2020 was the second-highest in a record going back more than 100 years. The past year in the Arctic was 1.9 degrees Celsius above the 1981-2010 average, surpassed only by the record-hot 2016. For nine of the past 10 years, average Arctic air temperatures were at least 1 degree Celsius above the 1981-2010 standard, the report card said.

– Sea-surface temperatures soared in much of the Arctic Ocean, hitting an August average that was 1 degree Celsius to 3 degrees Celsius above the mean recorded from 1982 to 2010. Temperatures were exceptionally high in the Laptev and Kara seas, where ice loss occurred particularly early.

– Arctic sea ice extent reached its second-lowest minimum in September, larger only than the record-low reached in 2012. In addition to the extreme minimum extent, the ice pack at its seasonal March maximum has changed composition: About a third of it was once ice that was four years old or older, but now it is mostly one-year ice, with that very old ice making up only 4.4 percent.

– Permafrost coastlines are being eaten away in bigger chunks, and the erosion hotspot is the Beaufort Sea coastline stretching from Alaska to western Canada. In the first two decades of 21st century, sites along the Alaska and Canadian Beaufort had erosion rates 80 percent to 160 percent higher than those recorded in the last two decades of the 20th century.

The changes are not uniformly negative. Bowhead whales in Alaska and Canada appear to be reaping some benefits of the warming ocean, at least for now, the report said.

Loads of zooplankton flowing north through the Bering Strait into Arctic waters have increased substantially, a product of dramatically increasing heat flux through the strait. The result, the report’s chapter on the whales said, has been an expansion over the last 30 years in the Pacific population, though the Atlantic and Sea of Okhotsk populations are still struggling.

But even that good news has caveats. As ice retreats, dangers are moving in, the report warned. Sea ice retreat has allowed orcas to move north and prey on bowheads. Human activity that can harm bowheads — such as industrial shipping, commercial fishing and petroleum exploration — is also expanding north as ice retreats, the report said.

For indigenous Alaska residents who hunt bowhead whales, conditions have changed dramatically, said Craig George, the retired North Slope Borough wildlife biologist who was the lead author of the bowhead whale chapter.

“There’s been significant changes to the hunting platform, the shorefast ice in the Arctic. in fact here in Utqiagvik, it hasn’t even set up yet,” said George, who was speaking from the northernmost U.S. community, where he lives. That is two months later than the ice used to form up, he said. “The hunters have had to adapt their methods,” with a lot of hunting from shore, he said in the news conference.

Another piece of good news in the report was evidence of growing international attention on the Arctic. One chapter in the report recapped accomplishments of the year-long Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate, known as the MOSAiC Expedition. In that project, scientists spent full year in the ice pack collecting data.

“MOSAiC is an experiment that as a scientist you dream about. It is an incredible opportunity to spend a year on the ice watching the seasonal transitions from fall to winter to spring to summer and back to fall. It is an opportunity to study the Arctic Ocean as part of an interdisciplinary team examining the interactions of the Arctic system between atmosphere, sea ice, ocean, biogeochemistry, and ecosystems,” Donald Perovich, one of the expedition scientists, said by email.

Perovich, of the Thayer School of Engineering at Dartmouth College, served on the sea ice team and is the principal investigator on a product studying sunlight and mass balance. Now that the fieldwork is completed, he said, scientists are examining MOSAiC data.

At the same time, however, scientists including Thoman are concerned about the loss of more routine data. While MOSAiC is “cool” and “the biggest Arctic experiment ever done,” it was a one-time expedition, he said. Meanwhile, budget cuts at the National Weather Service have forced automation of rural Alaska weather stations that used to be staffed by people. Without human observers at those sites, some information needed to track climate — for example, records indicating whether precipitation is snow or rain — is being lost, he said.

This story has been updated to include comments from report authors made during an online news conference introducing the report.