Coast Guard crew trains in Greenland for an Arctic maritime crisis

Exercise Argus focused on search-and-rescue and pollution response off the coast of Greenland.

Crews from first responder agencies of several nations, including the U.S. Coast Guard, conducted a major search-and-rescue and pollution management exercise off the coast of Greenland earlier this month.

Exercise Argus 2022, led by the Kingdom of Denmark’s joint Arctic command, comes at a time of heightened geopolitical tensions, increasing traffic in the north and rapid environmental change.

Law enforcement and military services from Greenland, Denmark, France and the U.S. participated in the annual exercise, which ran from July 4 to July 9 in Sisimiut and Nuuk. Exercise Argus began in 2018 as a search-and-rescue training and expanded last year to include maritime environmental response.

This year, the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Oak participated, while the USCGC Maple participated last year — offering the Coast Guard an opportunity to train a new crew.

“A lot of the folks that are up here now would be the same people that could potentially be deployed for a real-life event,” commander Daniel Schrader, a spokesperson for the U.S. Coast Guard, told ArcticToday in early July. “Making those connections and working alongside everyone now — it’s a lot easier if we have to come back” to respond to an emergency.

The U.S. Coast Guard only has two functional icebreakers, both homeported on the West Coast. Seasonal exercises like these allow vessels that aren’t ice capable, such as cutters, to expand their range and abilities.

International collaboration is another key part of exercises like these and through organizations like the Arctic Coast Guard Forum. Working with partners has long been an important part of operating in the Arctic, with its harsh conditions and long distances.

Although U.S. Arctic territory lies on the Pacific side of the Arctic, the nation has a continued interest in the Atlantic Arctic for strategic and commercial reasons.

“We have territory in the Pacific side, but we still have an interest, we still are a key player in the Atlantic Arctic,” Schrader said. “All the other Arctic nations, except for Russia, have territory on the Atlantic side, so being able to coordinate with all of them is key to any success we have.”

The division in partnerships isn’t just geographic.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, international action in the Arctic — as in other parts of the world — was disrupted.

Although the U.S. paused its work on the Arctic Council, the U.S. Coast Guard continued emergency cooperation with Russia in the Bering Strait. But other partnerships with Russian counterparts have been put on hold, while collaboration with other Arctic nations has gained force, particularly as Sweden and Finland work to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

A changing Arctic could bring conflict to the region, U.S. President Joe Biden said at a U.S. Coast Guard change of command ceremony in June.

Environmental threats are also gaining more attention in the Arctic.

As sea ice diminishes, more vessels are entering the Arctic, increasing the chances of an emergency, including ships in distress and oil or fuel spills in an ecologically sensitive region.

Even as this year’s Argus exercise was underway, three cruise ships visited Nuuk, each with 1,000 to 1,400 passengers — underscoring the importance of emergency response, Schrader said.

If a ship runs into trouble — if, for instance, the engines stop working or the ship runs aground — “you could find yourself quickly in a scenario where you have 1,000-plus passengers that are on life rafts in the Arctic, in addition to the vessel sinking and the pollution response for that. So it’s important for us to get ready now for things that may happen in the future.”

Such crises would be devastating to people and the environment, yet it can be difficult to respond quickly to such complex crises.

Drift modeling is one such challenge. It can be difficult to understand how pollution or ships could drift in the currents because of data gaps on weather and tidal flows.

And the icy environment of the Arctic presents challenges for cleaning up pollution in a vulnerable ecosystem.

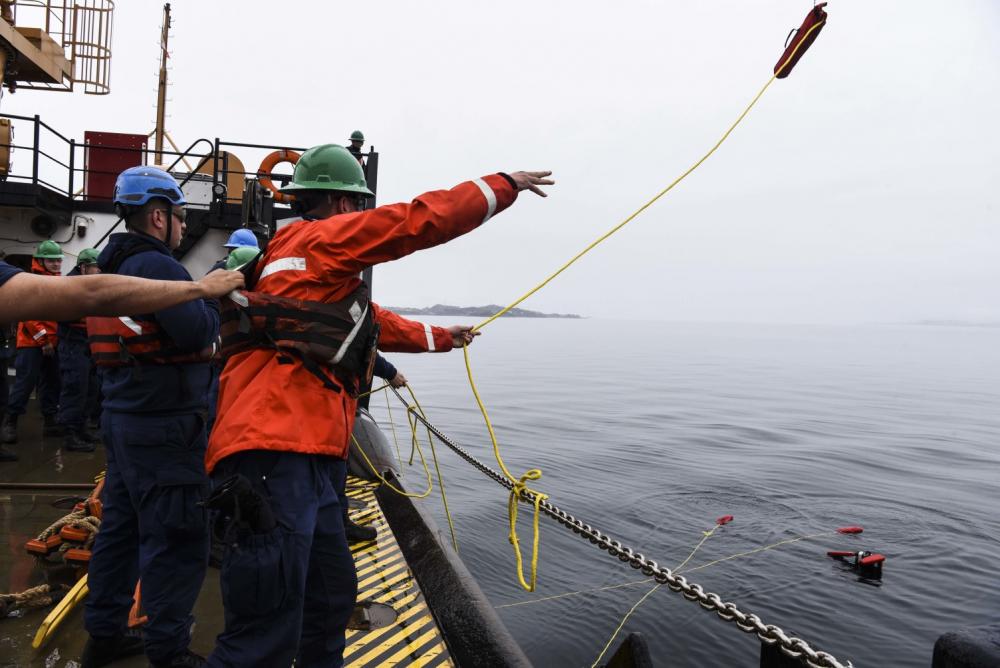

Pollution responders practiced deploying oil containment booms, inflatable rubber walls that can encircle contaminants in the water.

“The equipment that they have in Greenland is really cutting edge,” Schrader said. “It’s really effective and inflates on the ship — they inflate it and it is ready to go.”

And participants also get creative with the conducting the drills in an ecologically sensitive way.

Last year, the Danish command brought large drums full of popcorn to use as an environmentally friendly stand-in for contaminants – to see how it would shift on the currents and how to maneuver the equipment to clean it up.

The Danes were relieved when the exercise was over and their offices were no longer filled with popcorn, participants said.