The Coast Guard is launching small satellites for Arctic search and rescue

Communications in the Arctic are “woefully inadequate,” experts say — so the Coast Guard is launching new satellites for search and rescue.

Ice melt is opening the Arctic up to new maritime activity, from shipping routes to tourism. Yet only a small fraction of the region — less than 5 percent — has been charted to modern standards. And despite the warming conditions, it remains one of the most extreme environments in the world.

“What if a vessel transiting encounters a seamount that’s not charted, and now we have a vessel run aground up there?” Paul Zukunft, the U.S. Coast Guard’s outgoing admiral, asked in a recent address at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

The Coast Guard doesn’t just patrol American shores to stop trafficking and maintain security; its vessels also perform important search-and-rescue activities. Yet according to a recent report on homeland security, ineffective communications systems could make such missions in the Arctic much more dangerous than elsewhere, “given the vast distances, risky operating conditions, small population, and very limited infrastructure.”

Communications, the report’s authors say, are “square one” of all missions; little can be accomplished without them. Yet experts consulted for the report called the current systems “woefully inadequate,” with patchy, unreliable voice communications and extremely limited data transmission.

“Right now, our communications hover just above the horizon,” Zukunft said.

Currently, the Coast Guard relies upon radio communication and some limited satellite capabilities. Cell phones rarely work in the region, and transmitting data is even tougher. The experts called for better methods to transmit audio, text, images, video and more anywhere, anytime.

Enter tiny satellites.

“The United States Coast Guard is investing in CubeSats to improve our persistent coverage for search and rescue for distress beacons,” said Zukunft.

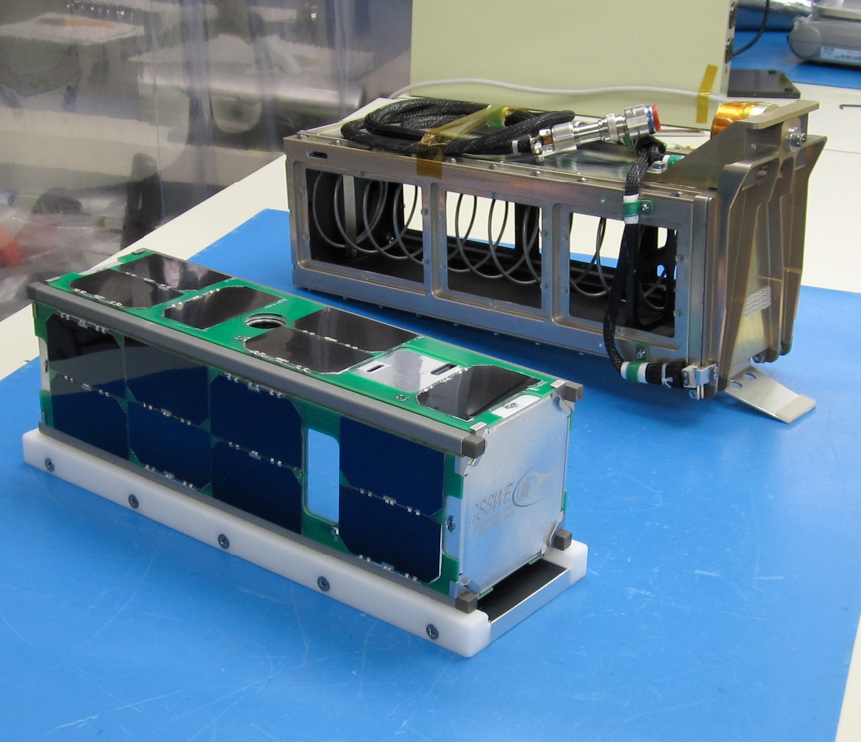

CubeSats are small satellites—in this case, about the size of shoeboxes—often used for space research. Because of their diminutive size, they can be launched with other, larger satellites, and they only cost about $25,000 to build — making them much more affordable, compared to other orbiting systems.

“One of the benefits is the cost to launch, because you’re sharing a ride,” says lieutenant commander Samuel Nassar at the Coast Guard’s research and development center in New London, Connecticut. “Almost like they’re carpooling together.”

The Coast Guard’s two CubeSats will catch a ride on the Department of Homeland Security’s Polar Scout mission, set to launch on or after September 30.

The systems will detect signals from those in distress and alert the nearest command center to deploy a rescue mission. The signals, called emergency position indicating radio beacons (EPIRBs), are carried on board vessels to transmit distress in the case of a crisis. Last fall, a mobile command-and-control station was established in Fairbanks, with another CubeSat ground station coming to New London next month.

Essentially, the satellites will make the search part easier in order to conduct rescues more effectively.

The two CubeSats will provide approximately three hours of Arctic coverage every day, passing over the North Pole 15 or 16 times a day for about 12 minutes at a time.

Of course, communications can only go so far in keeping the Arctic safe. The authors of the RAND report highlight the importance of preventing threats and hazards in the first place.

“Once a response is needed, however, ensuring that the right people and assets are available and can be deployed rapidly will be key,” they write.

The report’s authors worry that their advice to strengthen communications won’t be heeded until it’s too late.

“I fear that as in so many other cases around the world,” says Abbie Tingstad, lead author of the report, “it takes a crisis to motivate action.”

It’s not that decision-makers aren’t aware of potential problems, she says, but more urgent short-term issues are often addressed first. The challenge will be demonstrating the urgency of strengthening Arctic communications before crisis hits.

Nassar says the CubeSats could be a “game-changer” for both commercial and military communications.

“CubeSats could be a solution,” he says. “This mission is to explore that possibility.”