Combine diesel, renewable energy for big savings, Nunavut study says

Cleaner, greener energy could mean millions of dollars in savings for Nunavut communities and more self-reliance from the South, according to a new study by a team of researchers from the University of Waterloo.

And the “stars are aligning” in Nunavut for just such a move towards renewable energy sources, said Paul Crowley, the World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic director, on Jan. 4.

The WWF sponsored the study, which was researched and written by the Waterloo Institute for Sustainable Energy.

“Knowing Nunavut’s energy infrastructure is in need of renewing, and there has to be investment in that infrastructure soon, we can invest smartly in our future. The smart investment would be into renewable hybrid energy sources,” Crowley, a longtime Iqaluit resident, told Nunatsiaq News from Ottawa Jan. 4.

That’s the same conclusion reached by the Waterloo researchers, who issued a joint news release with WWF in December 2016.

The researchers studied five Nunavut communities they believe hold the greatest potential for benefiting from a move to renewable energy.

Those communities are Arviat, Baker Lake, Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet and Sanikiluaq.

Over 20 years, communities could cut down on greenhouse gas emissions by a range of 26 percent (Iqaluit) to 74 percent (Baker Lake), according to the study.

And those communities could save between $9.3 million (Arviat) and $29.7 million (Iqaluit) in energy costs, the researchers said.

The study used factors like the age of current energy infrastructure, the availability of local renewable energy, future demand for energy and the cost of transporting fuel.

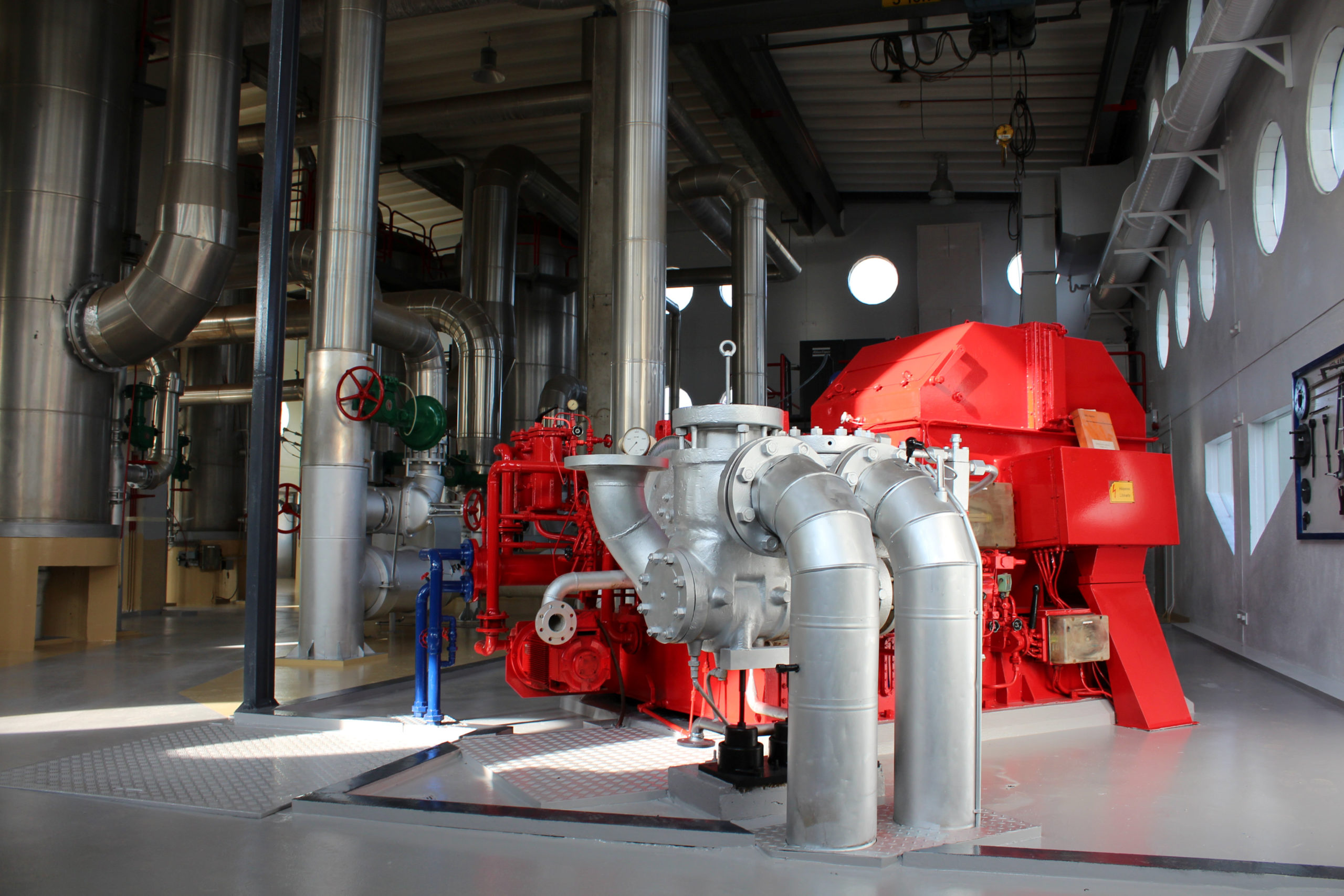

For each community, researchers designed a potential hybrid energy system, drawing on local renewable sources and existing diesel generating plants.

But those plants are near the end of their life in almost every Nunavut community.

With such a strong business case for renewable energy, the economic benefits of moving to greener energy “are too significant to ignore,” WWF’s president, David Miller, said in the Dec. 22 release.

“We know it leads to massive savings… and we know it’s better for the environment. What communities need now is funding to support rapid renewable-energy deployment,” Miller said.

How to finance new energy projects in Nunavut was one of the main issues raised at the pan-Arctic renewable energy summit the WWF co-hosted with governments in Iqaluit in September, Crowley said.

Public funds from the federal government should play an important role in Nunavut, where funds for capital projects are especially hard to find, he added.

That’s why the WWF has lobbied Ottawa to set up a renewable energy fund similar to one the United States government has created in Alaska.

“That really prompted the transition to renewable energy in Alaska,” Crowley said.

Over 60 communities in Alaska, whose climates and remote locations are comparable to Nunavut communities, use some form of renewable energy.

“It’s not experimental — the transition can be done in a systematic way that has already been proven to work in other places under very similar conditions.”

But the Government of Nunavut should look at running pilot projects in a few Nunavut communities in just such a systematic way, said Crowley.

It would make more sense to study the potential for local renewable energy sources before running a hydro line from Manitoba into the Kivalliq region, as has been long proposed, the director said.

And Crowley pointed out that the Waterloo researchers found renewable energy can be just as reliable as more popular energy sources like diesel.

“We feel very confident that our studies show that Arctic communities can technically and economically depend on renewable energy,” the study’s chief investigator, Claudio Canizares, said in December.