Continuous satellite coverage in the Arctic could help predict extreme weather around the globe

Despite its importance to global weather, satellite coverage of the Arctic is often insufficient — or simply unavailable.

This past winter, the Arctic didn’t stay put. A polar vortex bulge brought extremely low temperatures to the U.S. East Coast; Niagara Falls began to freeze, and even Florida saw snow.

This past winter, the Arctic didn’t stay put. A polar vortex bulge brought extremely low temperatures to the U.S. East Coast; Niagara Falls began to freeze, and even Florida saw snow.

These events will only become more common as the climate in the Arctic and around the world changes rapidly. Yet it’s becoming harder to predict weather like this.

But if meteorologists had access to continuous satellite monitoring of the Arctic, they say, predicting the next polar vortex bulge — and more — would be much easier.

“That’s exactly the kind of thing where you could benefit if you had a highly elliptical system in place,” says Juhani Damski, director general of the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

[Danish military’s first satellite will keep eye on ships in Arctic]

“Weather is the boss,” he adds. Weather affects all parts of life, and weather in the Arctic is particularly important — and, he says, satellites are key to observing those Arctic conditions.

“Satellite information is often the only way to get good coverage of the area,” he said recently at the Woodrow Wilson Center. However, he pointed out, such coverage is often insufficient or unavailable. Currently, there is no continuous monitoring of the Arctic.

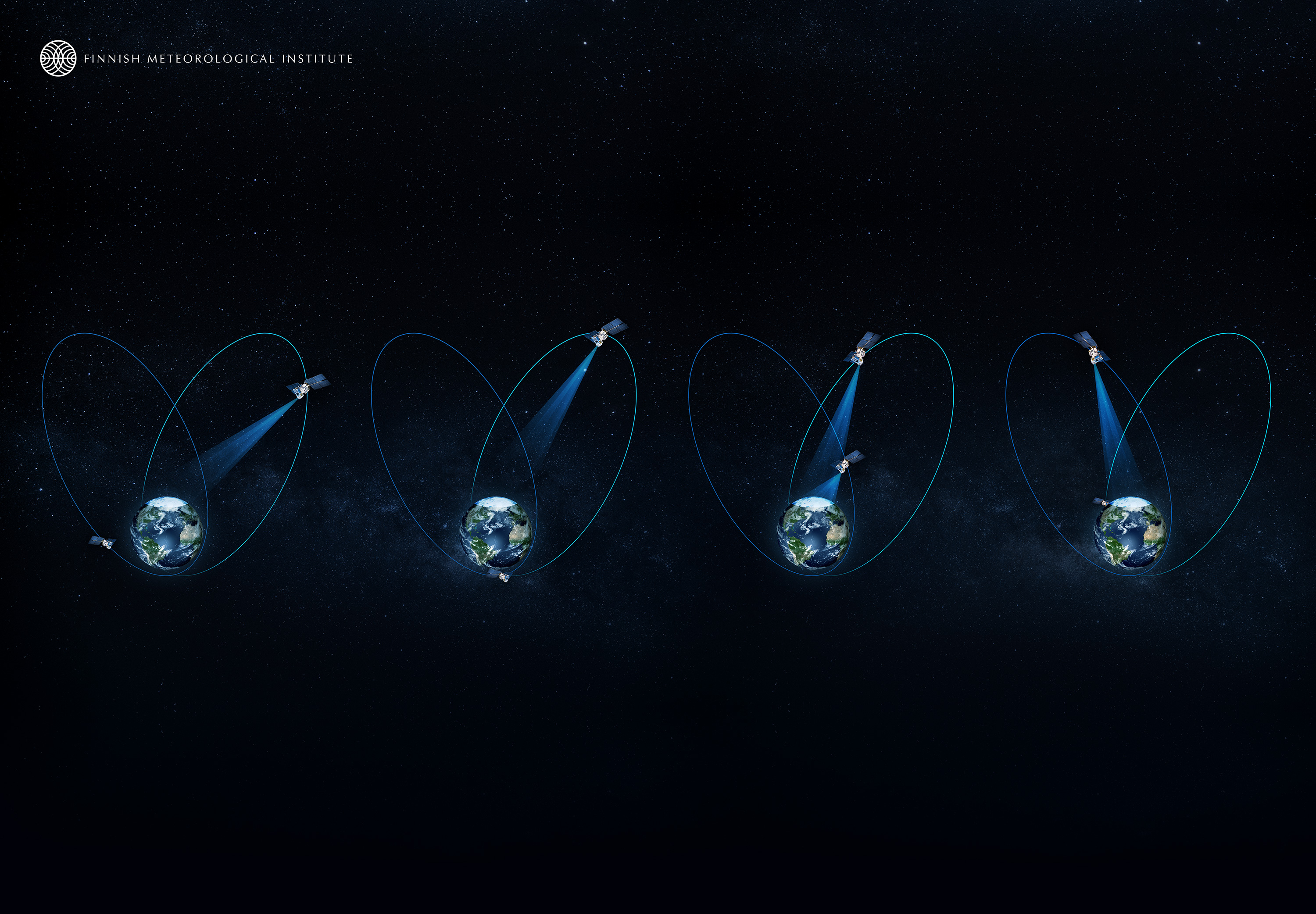

But the dream, he says, would be something called a highly elliptical orbit mission: Two or three satellites positioned to keep an eye on the Arctic at all times as the earth travels its elliptical path.

Two or three satellites in highly elliptical orbits could keep a continuous eye on the Arctic. (Finnish Meteorological Institute)

The data collected wouldn’t just benefit Arctic researchers and decision makers; as observers are fond of saying, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. Weather patterns observed in the circumpolar have enormous consequences all over the globe.

Yet the lack of continuous satellite monitoring, particularly in a rapidly warming region, means forecasters often fly blind, or work with incomplete data.

“If you look at the whole scene, there are critical pieces missing,” says Árni Snorrason, director general of the Icelandic Meteorological Office.

“We need observations — and in Arctic areas, we don’t have all the observations we need,” Damski adds.

And, he says, timing is critical when it comes to long-term analyses. “We have to do the measurements today; we can’t go back to yesterday to do the measurements.”

[Meteorologists urge closer collaboration to improve safety, climate assessments]

Launching new satellites is a staggeringly expensive endeavor. However, Juhani Damski and Jouni Pulliainen at the Finnish Meteorological Institute outlined in an interview the ways in which meteorologists could achieve this dream.

The Canadian Space Agency is looking into expanding telecommunications above the Arctic, the Finnish meteorologists say, and could be a good candidate for adding a weather-tracking satellite or imager as well.

“The easy way would be to add a relatively simple imager into this kind of communications satellite that can be used for monitoring the clouds and their movements,” Pulliainen says. Such an imager wouldn’t add much to the mass — and therefore the expense — of the satellite.

“That would already give us a very big impact in meteorological monitoring,” Pulliainen adds — and it might provide the momentum and data needed to support a larger, more complex satellite for Arctic meteorology.

The European Space Agency has explored options for launching a highly elliptical mission focused on meteorology; the next challenge is moving from exploration to reality.

There are also a number of small companies and start-ups experimenting with micro-satellites, Damski points out. “There are huge possibilities in space,” he says. Such possibilities may match the huge changes happening on Earth.

As Arctic transportation, from shipping to cruise ships to flights, increases in the circumpolar region, situational awareness also needs to improve — including information on weather and environmental challenges.

“When there is an increase of activity in the high latitudes,” Pulliainen says, “there should be better information sources, better forecasts available.”

The meteorologists hope that by combining what these satellites can do — from improved telecommunications to GPS positioning, as well as meteorology — the benefits will become attractive enough that the larger agencies (such as the European Space Agency, the Canadian Space Agency, NASA and NOAA) will want to move forward on them.

“In order to make a new satellite mission, it’s a big, big thing,” Damksi says. “This is a catch-22 in a way. You know that there are benefits, but you are unable to show them.”

He pointed to Finland’s focus on meteorology during its chairmanship of the Arctic Council and highlighted the importance of collaboration among Arctic countries — and countries with an interest in the region — to share knowledge, research and resources.

“We know it will take a long time,” Damski says. But, “in the future, there will be even greater need for such a thing.”