Coronavirus isn’t the only serious respiratory illness threatening Arctic residents

Preventable diseases such as RSV and the flu grip Northern communities in North America every year, straining already limited health systems.

So far, there have been zero confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Nunavut. But experts are also worried about the spread of other respiratory illnesses, including tuberculosis and RSV (respiratory syncytial virus), which appear in the territory every year and have long-lasting health effects.

RSV is particularly dangerous for young children.

It’s the most common cause of lower respiratory infections in children around the world, and the top reason why infants are admitted to hospitals in the developed world, researchers say. Even among children not considered at risk for RSV, it can be a dangerous illness, causing significant stress for families no matter the outcome.

For many adults, the symptoms are similar to a common cold. But for young, vulnerable babies, RSV is a serious ailment that can land them in the hospital.

Those most at risk for the virus are babies born prematurely or those with heart or lung conditions. And, research in Canada has shown, babies born in Inuit communities are also at much higher risk than other young children in the rest of the country.

[How the Arctic’s limited infrastructure could make coronavirus deadlier in the region]

Every year, particularly from about March to June, RSV infections rise throughout communities in Nunavut. (RSV isn’t widely tested for, so it’s difficult to determine yet whether lockdown measures and distancing guidelines introduced to slow the coronavirus have also slowed RSV’s spread this year. But health providers in Nunavut have reported at least some new cases this year.)

Nearly all Inuit infants in Canada admitted to the hospital have lower respiratory tract infections, said Anna Banerji, a pediatric infectious disease specialist and a professor at the University of Toronto’s faculty of medicine. RSV is the leading cause of those infections, Banerji told ArcticToday.

Inuit children living on Baffin Island have the highest known rates in the world of bronchiolitis, a condition resulting from RSV that requires hospitalization, according to a 2012 study by Thomas Kovesi, a pediatric respirologist at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario and professor at the University of Ottawa’s faculty of medicine.

About half of Inuit infants in Nunavut had serious cases of RSV in their first year of life, compared to 2.7 percent in southern Canada and the United States, Kovesi found.

In the United States, RSV is the most common cause of bronchiolitis — when the small airways in the lungs become inflamed — and pneumonia in infants under the age of one.

Rates of RSV are higher among Alaska Native communities than among non-Natives, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Alaska Native infants have one of the highest hospitalization rates in the country for lower respiratory tract infections and RSV.

Alaska Native infants from the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta are hospitalized because of RSV three times more than other infants in the United States, and the “RSV season” is twice as long, one study found.

Inuit and Alaska Native children also “often experience repeated, severe RSV infections in the same season, which is unusual elsewhere,” Kovesi wrote.

More than one in 10 infants admitted to Qikiqtani General Hospital in Iqaluit subsequently need to be transferred to pediatric intensive care in a southern hospital. And in many cases, that’s after first being medevaced to Iqaluit from their home community.

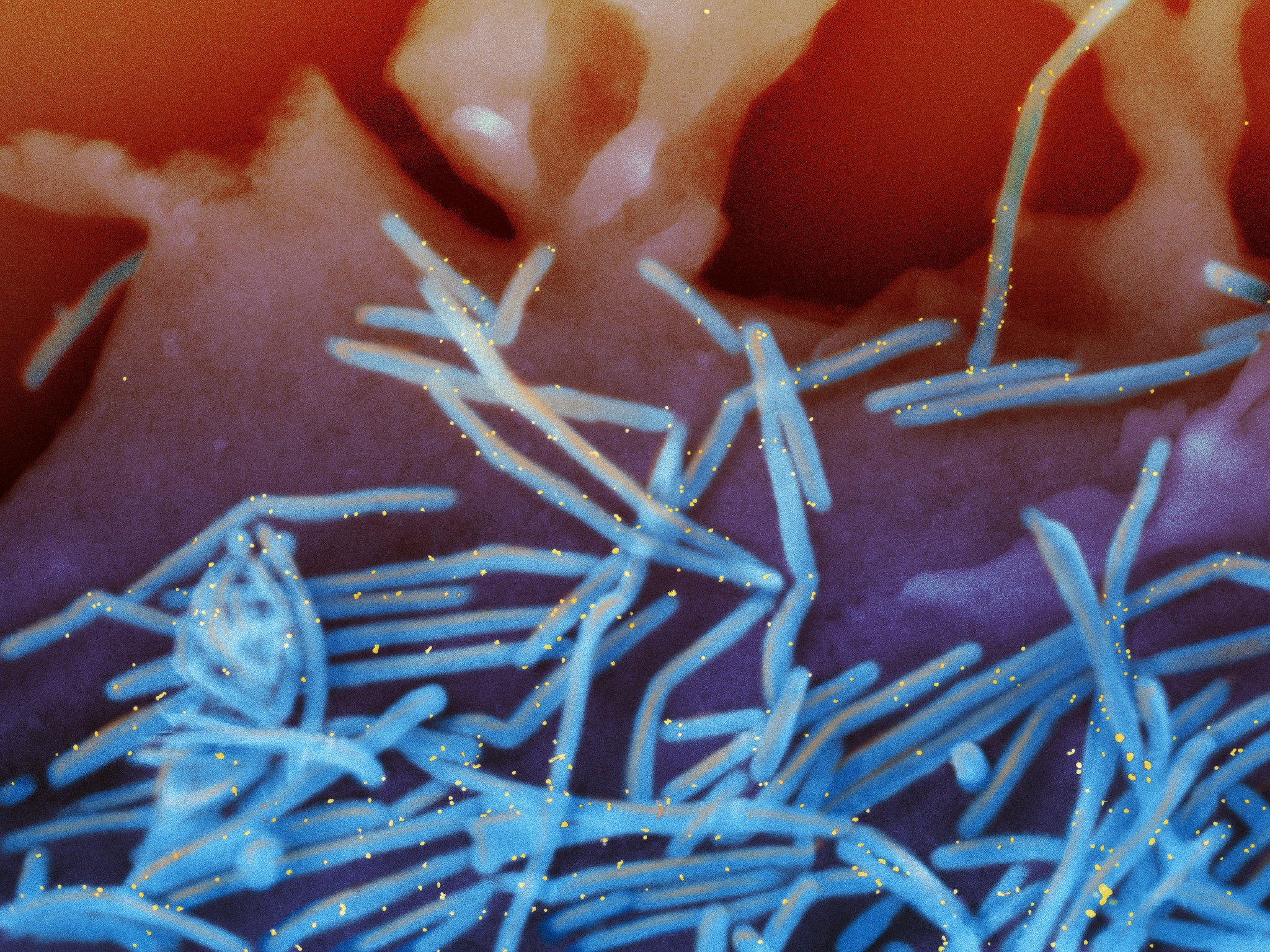

Indigenous communities are also at higher risk for certain other respiratory illnesses, such as influenza and tuberculosis. These infections can cause long-term issues, such as asthma and lung damage, that create other health challenges.

There are a number of reasons for the disparity, Banerji and Kovesi say, including poverty, poorly ventilated and overcrowded housing, under-nutrition and exposure to tobacco smoke. There’s also limited access to health care; for example, Nunavut has seven ventilators for the entire territory.

In Alaska, a lack of running water has been linked to an increased risk of respiratory infections, likely because of the difficulty in washing hands regularly.

But there are established ways to prevent RSV and other respiratory infections from taking hold in the first place.

A medication called palivizumab (brand-name Synagis) is an antibody already given to preemies and infants particularly vulnerable to RSV. It could also be given to Inuit infants to reduce hospitalizations, long-term complications and deaths.

“The thought of having these young babies in the hospital or in the intensive care unit when there’s something that can be done, it seems not to make a lot of sense,” Banerji said.

The children’s geographic isolation and lack of access to prompt medical services can mean longer hospital stays and worse outcomes, she said.

“A baby could be in the community and it could be a two-day wait before they end up coming down to a children’s hospital,” Banerji said. “Because it’s hard to get the air ambulances up into these remote Arctic communities.”

[Inuit infants need access to medication to prevent respiratory illness]

Banerji’s work prompted a petition asking the government to offer the medication to Inuit infants; the petition now has more than 128,000 signatures.

She’s hoping to raise awareness in Nunavut that an effective antibody exists.

“Part of it is letting the people in the communities know,” she said. “And if it’s important to them, if they think it’s a major issue, then really it needs to be the people in the communities, the grassroots rising up, saying to the government that this is something that we want.”

The cost of Synagis is between $5,000 and $9,000 per child each year. But providing the medication, though expensive, would actually help save money on medical costs, Banerji’s research has indicated.

Each medevac in Nunavut costs about $20,000, Kovesi said.

Nunavut is one of the most cost-effective places to give the medication to infants, Banerji said, “because the medevacs from these communities down to the regional hospitals and the children’s hospitals are so expensive, and the rates of the RSV are so high.”

Michael Patterson, Nunavut’s chief medical officer, has said that there isn’t enough evidence that the antibody prevents RSV-related hospitalizations and deaths. (The government of Nunavut did not respond to inquiries for this story.)

Yet the medication has proven effective for other vulnerable babies who receive it, which makes it worth conducting the research necessary to assert its effectiveness among more infants in Nunavut, Banerji said.

A similar study is currently underway in Nunavik.

In 2011, the Canadian Pediatric Society recommended vaccinating Inuit infants with palivizumab. However, in 2018, they clarified their position, stating that improving housing, among other measures, would be more effective.

Kovesi sees these two solutions as complementary.

“We’re trying to deal with the problem in kind of two different directions,” he told ArcticToday. “They’re totally complementary. I think they both need to happen.”

In his work, he’s focused on housing and indoor air quality.

Houses in Nunavut are usually tightly sealed to keep the cold out and to maintain energy efficiency. They’re also small and typically very crowded. While the average southern Canada house has three people, Nunavut homes have double that — and they tend to be smaller, as well.

“The more people you have crowding, the more likely kids are to catch respiratory infections such as RSV and tuberculosis,” Kovesi said.

There are two primary ways to make sure a house in Nunavut is ventilated properly: a heat recovery ventilator (HRV) and kitchen and bathroom fans. But most homes didn’t have HRVs, and many of them had broken or malfunctioning fans.

About two-thirds of Nunavut housing was not properly ventilated, Kovesi found in his research.

“If you have a house that is very tightly sealed, and you don’t have a working HRV, you’re basically living in a plastic bag,” he said.

Kovesi suspects that ventilation plays a role in how respiratory illnesses are spread. Typically, the flu or RSV is transmitted via cough or sneeze droplets, or contact with a contaminated object, like a doorknob.

But in a tightly sealed house, droplets from coughing and sneezing could become aerosolized, Kovesi said. “If you sneeze in the house in Nunavut, perhaps it forms a kind of like aerosol cloud of virus that everybody breathes in,” he said.

In addition to being more infectious, this form of transmission could affect how severe the illness is. With the flu, for instance, those who are infected with droplets or contact usually get the typical symptoms — fever, chills, coughing.

“But if you catch influenza through the aerosol route, you get pneumonia,” Kovesi said. The same may be true of RSV, he said, which could explain the severity and ubiquity of the virus in Northern communities.

High rates of tuberculosis are similarly linked, in part, to poor ventilation, he said. “There’s very strong evidence that lower rates of ventilation in a building increases the risk of TB.”

“The importance of dealing with ventilation is, you’ll also reduce risk of infection with all the other common respiratory bugs, be it influenza, or TB, or likely even coronavirus.”

According to Kovesi’s research, installing HRVs in Nunavut homes led to fewer respiratory illnesses.

Since his findings were published, all new housing in Nunavut is now built with HRVs.

But retrofitting older houses with the ventilation systems can be costly. It’s about $6,000 to install a new system if a house already has ductwork — more if ductwork needs to be installed as well.

Homeowners also have to clean them twice a year — especially in places with dusty, unpaved roads.

Reducing overcrowding is another way to prevent illnesses, and Nunavut also needs more housing, he said.

And those who smoke in their enclosed porches should consider going fully outside, Kovesi said. “That enclosed porch is where the air intake is for your furnace. So if you smoke inside the porch, it’s going to re-circulate the smoke all around your house.”

Both Kovesi and Banerji pointed to a number of other issues resulting in poor health outcomes. At the root of these inequities in health care, Banerji said, is discrimination.

“There’s a huge difference in the way that Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are treated,” she said. “When you have Inuit babies that have at least as much risk of RSV infection as the premature or the cardiac kids, if not more, but they’re not eligible for the same treatment or equitable treatment — it’s part of a broader systematic issue that occurs in Canada.”

Banerji calls it “a different standard of care” for Indigenous communities — one that will continue to strain Canada’s health system.

The coronavirus pandemic could add pressure to an already fragile system, she said.

“If it’s a really bad RSV season and all these babies are being medevaced out, and all these elderly people potentially are at risk for coronavirus — it could be a real disaster.”

Lowering cases of RSV, she pointed out, would be one less demand upon an overstretched health system.

Right now, as families practice physical distancing amid school closings and travel restrictions, there may be a temporary drop in respiratory illnesses.

But viruses like RSV return every year, proving difficult to shake without serious intervention, the experts said.