Could a warming Arctic unleash the next pandemic?

Perhaps. But a more likely scenario would see new pathogens emerging in temperate regions and moving north, researchers say.

As the land and waters of the Arctic warm — potentially releasing pathogens — and as more species migrate toward the poles in a changing climate, those conditions could create more opportunities for viral spillover, according to recent studies.

But while it’s possible that pathogens could emerge from a thawing Arctic, there is a greater risk of new threats emerging elsewhere and then moving into the Arctic, experts say.

In one study, a preprint that has not been peer-reviewed or published yet, researchers resurrected 13 new viruses from the permafrost after thousands of years. These viruses, which only infect amoebas, “can survive up to 50,000 years in deep, ancient permafrost,” Jean-Michel Claverie, emeritus professor of medicine at Aix-Marseille University School of Medicine and one of the study’s authors, told ArcticToday in an email.

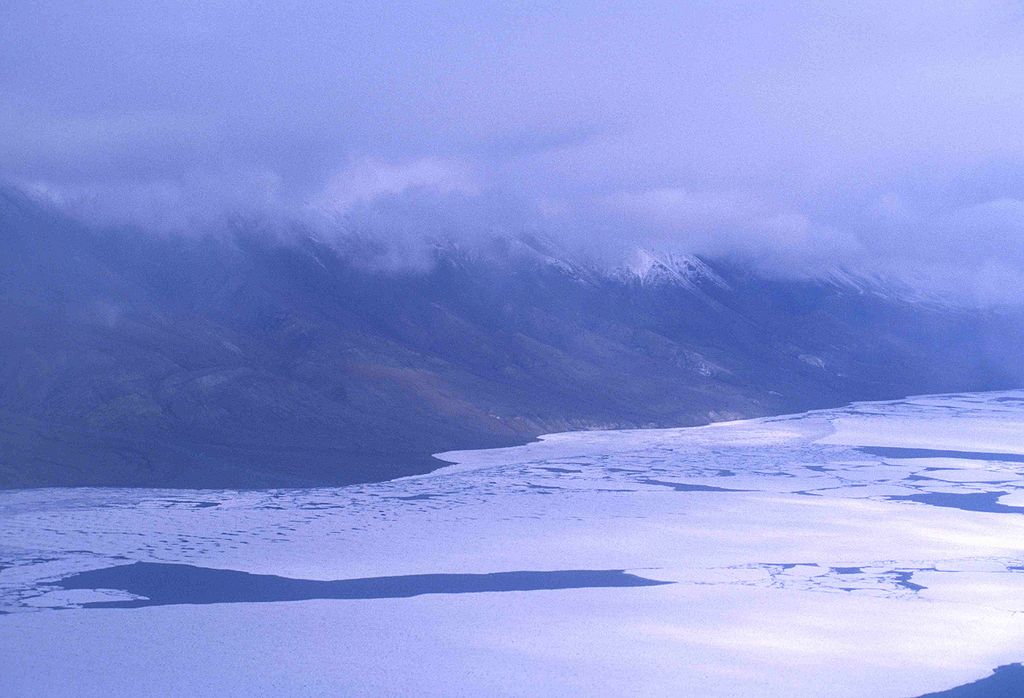

In another study published in October, researchers looked at the viruses in sediments from the soil and water of Lake Hazen, the largest-volume freshwater lake north of the Arctic Circle, located on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada.

Then they looked at the usual hosts for those viruses, as well as their close relatives. Viral spillover occurs when a virus infects a new host, which effectively allows viruses to expand their range.

In a warming world, that study found, Arctic viruses could have more opportunities to infect new hosts, which might then spread novel diseases.

At the same time that the Arctic environment is undergoing dramatic changes — in the second study, the researchers used glacier melt rates as a proxy for wider climate change — these global changes are also forcing species to migrate toward the poles, other researchers have found.

“Should climate change also shift species range of potential viral vectors and reservoirs northwards, the High Arctic could become fertile ground for emerging pandemics,” the researchers of the second study conclude.

But even if new viruses emerge, the possibility of such spread in the Arctic is theoretical at this point.

“We don’t know,” said Morten Tryland, a professor of infection biology and One Health at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences. “That’s the short answer.”

It is also unclear from this and other research whether there are pathogens hidden in the Arctic that could wreak widespread havoc, since not all viruses cause pandemics and the effects of bacterial infections would be limited to those who come in direct contact with them.

And while the Arctic is home to the thawing remains of victims from viral epidemics such as the 1918 flu and smallpox, it is unlikely for these viruses to remain viable for long periods of time, especially in unstable conditions that regularly thaw and refreeze.

In the preprint study, the revived viruses were able to infect amoebas, not people. There may be other viruses stored deep within permafrost that could be better suited for infecting plants, animals, and people, the authors argue.

Yet while the permafrost can serve as a freezer for pathogens, it is increasingly unstable. The very conditions that may cause it to release ancient viruses — cycles of thaw and refreeze triggered by climate change — could also kill the viruses before they locate hosts.

“Fortunately, the probability that these viruses would encounter their proper host is small,” Claverie wrote, because heat, light, and oxygen cause them to decay rapidly.

“We are definitely going to find more viruses as permafrost thaws out,” said Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan. “But viruses have to have a host to persist for a long period of time.”

It’s unclear whether viruses frozen for tens of thousands of years could even find a compatible host now, she said. Even if someone were to come into contact with a viable, human-infecting virus from the permafrost, they might not get sick, and they might not spread the virus. “It’s possible, but I don’t think it’s particularly likely.”

The other study, focused on spillover, warns of what may happen in a region where climate change is already happening quickly, especially in places with vast viral reservoirs and close mixing with animals and people.

The Arctic is ground zero of climate change, making it a particularly interesting case of what is already happening with animals, humans, and pathogens in a changing world. With this research, Tryland said, “I think they use the Arctic more like a model that can be used in other places.”

Climate change doesn’t just reshape environments. It also pushes animals into new places in an effort to survive — an effect that is accelerated by the ways humans use land, including agriculture, housing, and logging.

“We are destroying the natural habitats of the animals, so that is creating a lot more contact with wildlife,” Tryland said — which can mean more animal-human spillover. “So wildlife is really changing quite a bit. And they’re on the move, in a way, which also brings pathogens with them.”

While species are migrating toward the poles in a warming world, much of that migration is taking place closer to the equator, with spillover events more likely in these regions.

Pandemic threats are more likely to come from outside the Arctic than inside it. Insects and animals moving north, including birds, could spread deadly viruses like influenza, and changing human behavior in an increasingly accessible Arctic could also contribute to the spread of pandemic-potential viruses.

“We’re starting to see diseases that were restricted by that geography appearing in [new] places, and that’s only going to continue on a slow march northward and southward,” Rasmussen said.

A scenario that sees new viruses moving into the Arctic is “much more likely” than on where ancient viruses escape it, Rasmussen said. “Getting a virus that has never been seen before, by animals that are living in the Arctic, could be potentially really serious.”

Studies have also detected hundreds of thousands of viruses in ocean harbors, with the Arctic Ocean identified as one of the “virus diversity hotspots.” In fact, diminishing sea ice may be escalating the introduction of new viruses from the other oceans; a rapid increase in phocine distemper virus in Alaska marine mammals were closely linked to years with low sea ice.

But just because a virus is present in the water doesn’t mean it’s capable of infecting humans or animals. “We’re surrounded by viruses all the time, and the vast, vast majority of them don’t cause any infection in us at all,” Rasmussen said.

Many of the most concerning viruses aren’t spread by the water or soil itself but by increased contact during new interaction patterns. Animals that were once surrounded by ice may mix with each other more easily now, for instance.

“That might be even more of an immediate concern than the permafrost melting and viruses emerging from there,” one researcher told ArcticToday in 2020. “Not to say that couldn’t happen, but the thing that is happening right now is that animals and people are changing their behavior, coming into contact, and that’s leading to increased distribution of viruses as well as spillover of viruses.”

That has consequences not only for human health but also for the health of the animals that Arctic residents depend upon, such as for subsistence hunting and fishing. If pathogens disrupt food chains, for instance, it wouldn’t take a pandemic to affect the well-being of people in the Arctic.

A study from 2020 examined the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, spreading to new hosts. The researchers identified animals, including in the Arctic, that could be susceptible to the coronavirus. This potential scenario was particularly alarming because if animals were to fall prey to new viruses, they could affect subsistence hunting and food security in the North.

Other pathogens such as anthrax could potentially emerge from thawing permafrost. In 2016, thousands of reindeer were sickened and one boy died in an anthrax outbreak in Russia’s Yamal-Nenets region.

The outbreak followed two unusually hot summers in the region, and the surface of the tundra and riverbanks may have thawed and released anthrax spores from an outbreak in the 1940s.

“The permafrost is basically a natural freezer for storing those organisms. And because they’re a spore-former, they can withstand a lot of environmental strain,” said Jason Blackburn, a professor of medical geography and a principal investigator in the Emerging Pathogens Institute at University of Florida. “As a spore-former, they can survive for years or decades probably in the soil.”

Climate change can also affect where herds go, as changes in permafrost can close off or open up grazing areas and migration routes, offering potential exposure from more recent anthrax outbreaks. And it’s prolonging the thawing and growing seasons in the North, which may extend the time when animals encounter anthrax.

“These changing climatic conditions are opening up new migration routes to grazing areas and that might be putting animals at risk. It may not be a 10,000-year-old pathogen — it may be something that happened in more recent history — but it was an area that was being avoided and now it’s being used,” Blackburn said of the ways that new migration patterns may affect anthrax outbreaks.

Other environmental conditions could also spur outbreaks.

“If you’ve got a large number of animals and they’re putting a high demand in an already hot, stressful year and grasses are stressed and the animals are eating more soil — those are all recipes for anthrax in any year,” Blackburn said. Biting flies — which may flourish in warmer temperatures — could also amplify anthrax transmission.

And the 2016 outbreak could have been caused, or at least accelerated by, the introduction of unvaccinated reindeer into the herd.

“Before the 2016 outbreak, they stopped vaccinating because of the cost and all the effort and the disease was not there. So you had this sort of perfect storm — you have a population that is not immune to the bacterium, and you had these warm summers that were thawing the tundra and also uncovering old carcasses from 70 years back,” Tryland said. It’s a “dramatic theory, but it’s not impossible.”

The good news is, there is a very effective and relatively inexpensive anthrax vaccine for animals. “Getting vaccine out to those reindeer is probably the most effective, in terms of really reducing disease,” Blackburn said. When “you increase vaccine, you decrease human disease.”

While bacteria like anthrax are a serious concern for those who come into direct contact with grazing animals, it’s unlikely to spark a global outbreak, experts said.

“It is a localized disease,” Blackburn said. Anthrax outbreaks are usually limited to grazing animals and those who come into contact with them. In those cases, bacterial infections are usually treatable with antibiotics, and they are unlikely to spread on a wide scale.

As the Arctic becomes more accessible and more people enter permafrost-rich regions for industries like mining and oil drilling, companies should establish protocols for detecting and handling new pathogens, Claverie said.

Viruses and other pathogens can always surprise us, Tryland said. A few years ago, most virologists expected the next outbreak to be a deadly flu, but instead SARS-CoV-2 emerged.

“The next pandemic could be a lot of things,” Tryland said. “Everything is possible.”

But other global changes — inside and outside of the Arctic — are a greater concern to our well-being, he said.

For instance, animal populations across the globe have plummeted by nearly 70 percent since the 1970s, the World Wildlife Fund reported earlier this year. That’s a striking decrease in biodiversity that will have enormous ripple effects, including on environmental and human health.

“I’m a lot more worried about that than a new pandemic from the Arctic,” Tryland said.

The debate over whether the next pandemic will come from a warming Arctic can take oxygen from important conversations that are far more pressing, Rasmussen said — such as climate change and the risks it already poses around the globe.

“We should try to minimize this from happening. But do we really need to worry about stream runoff and virus transmission? Or should we worry more about the cause of the stream runoff, and the many other impacts that has?”

This article has been fact-checked by Arctic Today and Polar Research and Policy Initiative, with the support of the EMIF managed by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

Disclaimer: The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the author(s) and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.