Debris from another rocket launch is headed for Baffin Bay

Debris from a rocket launched in Russia to place a European Space Agency satellite into orbit is expected to land in Baffin Bay — and possibly pose a risk to local residents and wildlife.

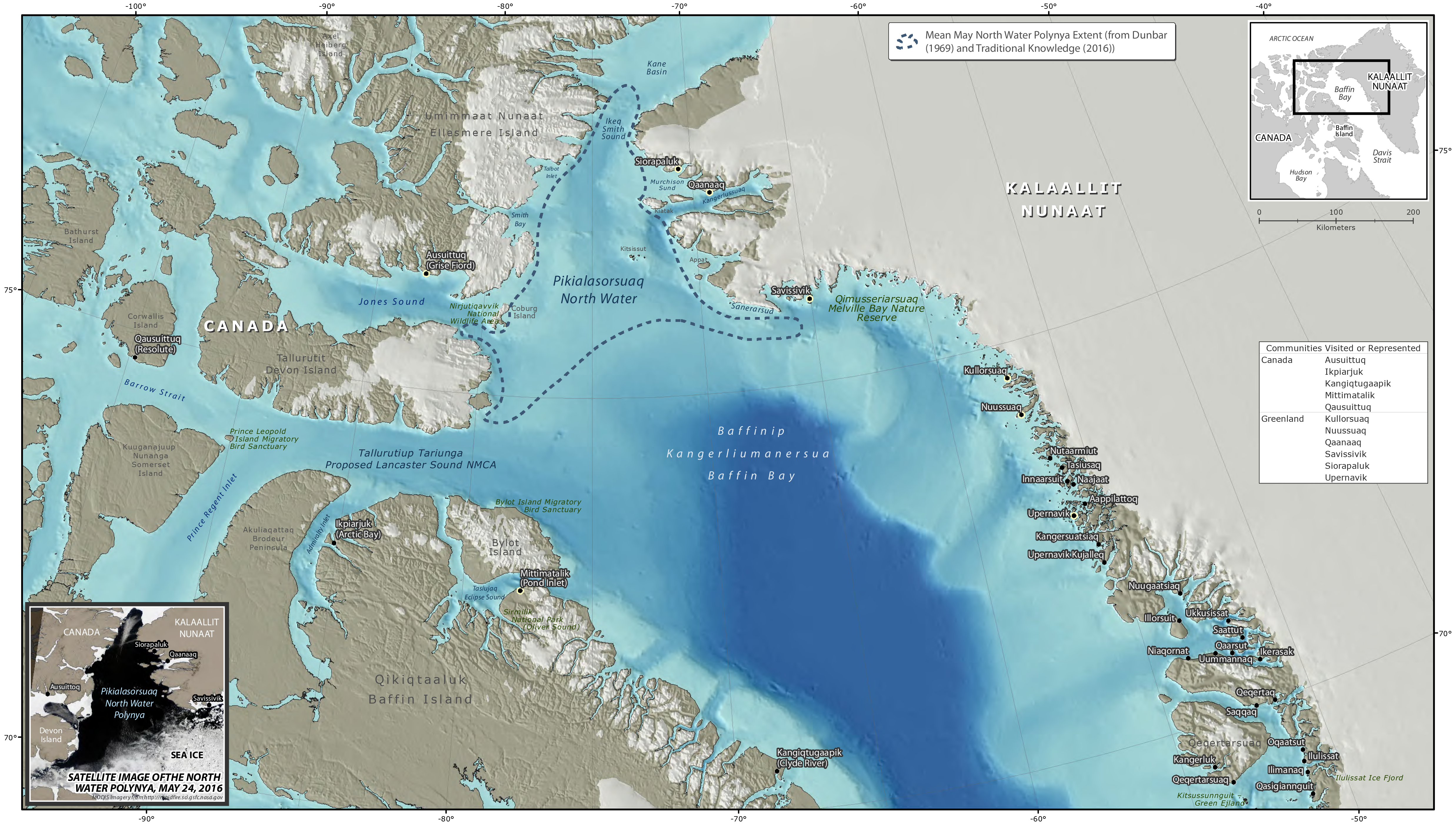

When the European Space Agency launches its newest satellite into orbit on Wednesday, one section of the Russian rocket propelling it into space is expected to splash down into Baffin Bay, between Nunavut and Greenland.

It’s similar to other recent launches, which have prompted protests by Inuit leaders who worry that debris crashing back to Earth could carry with it highly toxic fuel.

It would be especially concerning if the rocket stage landed in the North Water Polynya, or Pikialasorsuaq. Its year-round open waters are an important refuge for narwhal, beluga, walrus and bowhead whales, among other species.

“This is the most biologically important maritime zone in the entirely circumpolar Arctic, so, unintentionally, they have picked the worst possible place to drop these rocket stages,” said Michael Byers, a political scientist professor at the University of British Columbia who published a scholarly paper on the subject this past autumn.

[How debris from rockets launched far away is a risk to Inuit food security]

The rockets in question are relics of the Cold War: repurposed Russian SS-19 intercontinental ballistic missiles. By Byers’s count, more than 15 similar launches have followed the same trajectory over the past decade or so, with their spent second stages dropping into Baffin Bay. These drops so far seem to have avoided either Canadian and Danish territorial seas.

The big concern is the fuel used by these aging rockets, hydrazine.

“It’s a known carcinogenic,” said Byers. “It’s so toxic that anyone who’s working with it needs to use a pressurized Hazmat suit.”

Russia has offered reassurances that this fuel is burnt up as rocket debris falls back to Earth. Byers says he has good reason to think otherwise.

Scientific research has documented the health and environmental damage of hydrazine in places in Kazakhstan and Russia where similar space debris has landed, as Byers’ research paper notes.

“It’s absolutely devastating,” he said. “Entire populations of the Steppes of Kazakhstan who have liver cancer rates more than twice the regular level. Entire lakes that are devoid of fish because of residual hydrazine coming back to Earth in rocket stages.”

“No one has done any science into the effects of Arctic waters of this fuel. But you can extrapolate from the damage done in Russia and conclude that there must be a significant risk.”

[Toxic fuel from Russian rockets in Arctic waters raises environmental and legal issues]

As well, Byers cites an amateur video shot by United States Air Force employee in Thule that appears to show a rocket stage returning to Earth.

“You can see the light coming down to Ellesmere Island,” said Byers. “The light then separates into two parts. The stationary part is almost certainly a cloud of vaporized hydrazine. This is consistent with what happens in Kazakhstan and Russia: the stage makes it through the atmosphere but breaks up as it’s coming down.

“The residual fuel vaporizes and drifts down over hundreds of square kilometers. That hydrazine drift is what’s causing elevated cancer rates in places like Russia and Kazakhstan.”

The concern, said Byers, “is not the fact that the fuel is making its way into the ocean. It’s the fact the fuel is breaking out of the rocket stage and vaporizing and turning into a cloud, which then drifts down upon the Earth.”

The Canadian government has protested Russia’s practice of dropping its space debris into these waters, to no effect. Byers suggests other routes could be taken.

“It could be more cooperation with Russia to encourage them to use their newer, non-toxic rockets,” he said. “The Russians have non-toxic rockets. They’re just using these old ones because they’re cheaper.”

[Nunavut premier condemns Russian rocket launch, demands it be halted]

As well, Canada could apply pressure to the European Space Agency.

“We’re an affiliated member,” said Byers. “We must have more leverage there than we’ve been exercising so far—particularly because the European Space Agency prides itself on being the most environmental space agency in the world. And this is an environmental monitoring satellite that’s being launched.”

Canada could also do more to study the space debris’ potential impacts on the environment and human health.

“I wish the Canadian government would go and take water and air samples after one of these re-entries,” said Byers.

“They’d have to do it fairly quickly afterwards. Hydrazine doesn’t bioaccumulate like mercury or persistent organic pollutants. It’s there for a couple of weeks and then it’s gone. But it’s during those couple of weeks that the carcinogenic effects take place and the damage is done.”

A health study of nearby residents, meanwhile, could offer “a smoking gun, in terms of these launches actually causing problems,” said Byers.

In the meantime, Byers has a word of caution for residents of Grise Fiord on Ellesmere Island.

“It’s important that people realize that the risk is probably very small. But having said that, if I was living in Grise Fiord, I would spend 24 hours indoors, starting at 4 p.m.”

“Even if it’s a tiny risk, it’s an avoidable risk, if people were to just take shelter for 24 hours. And I certainly wouldn’t go out on the ice near the North Water Polynya [that] afternoon.”

The Government of Nunavut, however, does not seem worried.

“It is expected that the debris will fall outside of Canadian territorial waters and is considered a very low risk event. There should be no harmful effects to any community, the environment or animals near the impact area,” the GN said in a statement yesterday.

The GN said that, as a precaution, they are in contact with the federal government regarding the event and that the Nunavut Emergency Management office is monitoring the situation.

“Although very unlikely, if wreckage falls on land, there will be a coordinated effort to notify the public and recover the debris,” the GN said.