Decades-old documentary films preserve snapshots of Alaska Native cultures

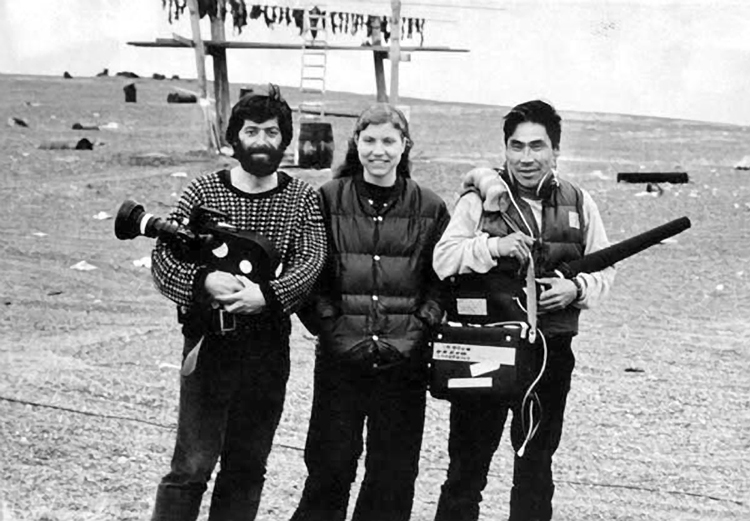

When Sarah Elder and Leonard Kamerling, two documentary filmmakers, met at a film festival more than 40 years ago, they were both searching for something new.

“We both had ideas about collaborative filmmaking, which was almost unheard of,” Elder said in a phone interview. “We couldn’t go to anyone as examples — there weren’t people doing it.”

This type of filmmaking — where the subjects of the films collaborate with the filmmaker in what is shot, how it is shot, who is interviewed, as well as the final edited piece — differed greatly from the anthropology films of different cultures shown in Elder’s college classes.

“The people never spoke for themselves,” she said.

Kamerling and Elder, now a professor of film at State University of New York at Buffalo, set out on a radical filmmaking mission, focusing on different Alaska Native communities.

Decades of collaboration have now produced over 10 films and hundreds of hours of video and audio recordings from Yup’ik, Inupiaq and Aleut communities. Today, this assemblage is now part of the Alaska Center for Documentary Film at the University of Alaska Museum of the North in Fairbanks, where Kamerling works as its curator of film.

The movies, shot in the 1970s and 1980s, show hunting, events, elders dispensing traditional knowledge, and everyday conversations between community members. They tackle serious topics, like alcoholism and domestic violence, and joyous ceremonies and lighthearted teasing among friends.

“The films never take a position of authority,” Kamerling said in a phone interview. “There’s no narration, no voice, no facts that teach you. You are there, you are with the people and you have to make that connection — we tried to give the audience the tools to make that connection.”

But without a model to follow, this new type of filmmaking was difficult at first. As Kamerling details in a recent article in the journal Arctic Science, the process of collaboration was “too informal and therefore often chaotic” in his first film shot in Tununak in the early 1970s, which Elder helped edit.

The team ironed out decision-making during subsequent productions, including how subjects and communities would participate in crafting the film.

“I began to understand that the films were indeed authored by us, and by our vision, and that the communities were not so much ‘determining’ the films but collaborating with us,” Elder wrote in a 1995 article in Visual Anthropology Review.

After making a few more films, Elder approached the village of Emmonak, a Yup’ik community at the mouth of the Yukon River in Southwest Alaska, with a film project. Elder had already lived and worked in the community for a year as a teacher, where she learned traditional Yup’ik dancing in the village dance house.

“When I walked in, I will never forget it, I was overwhelmed by its beauty and the sacred feeling in the room and the skills of the dancers and singers,” Elder said. “I said, ‘I want to make a film here, but I don’t want to make it until I’m a really good filmmaker,’ because I hadn’t made films yet.”

Elder’s connection to the village, as well as previous footage of other Alaska Native villages and the idea of collaborative filmmaking, helped her get approval from the community to shoot the 90-minute “Uksuum Cauyai: The Drums of Winter.”

Elder and Kamerling received special permission to film in Emmonak’s main dance house, considered a sacred place that didn’t allow photography or lights. While political leaders in their 40s and 50s opposed the idea of filming in the dance house, the older generation of leaders disagreed, according to Elder.

“They said, ‘No, you are wrong. We have seen more change that you have in our lifetime and this is a good way to document our culture,’ ” said Elder.

Elder and Kamerling started filming “Drums of Winter” in 1977 in Emmonak, where they lived and worked for multiple months. While the editing process for all their films was lengthy, “Drums of Winter” took the longest. It was completed in 1988.

The film features Emmonak elders talking to the camera in Yup’ik, which was translated into English subtitles by bilingual speakers.

Walkie Charles, now an assistant professor of Yup’ik at UAF and a native of Emmonak, helped with the language when some interpreters couldn’t capture vocabulary and grammatical concepts unique to the community.

“Things people would have missed, I caught because I’m from Emmonak and related to people (in the film) and know how they talk,” Charles said in a phone interview. “So when I came on, Len (Kamerling) was all like, ‘Where have you been?’ ”

The specific words and phrases were precious to the community, which throughout filming — and in years since — has experienced critical social and cultural changes due to outside influences.

Charles said he has seen the separation between generations grow as time progresses and there is more access to the English in the village. For Kamerling, this change came, in part, with the introduction of television.

“When we were in Emmonak, the first television satellite switched on,” Kamerling said. “Everyone already had television and it changed the social fabric literally overnight.”

In May, Kamerling went back to Emmonak for a showing of “Drums of Winter,” 40 years after the original production of the film began. He said many young people in the audience were using the English subtitles to understand what their relatives in the film were saying.

Still, for Charles, “Drums of Winter” is a good starting point to address how the Yup’ik people can strengthen their identity, who they are as a people.

“Some people say that culture died, but I like to say it went to sleep,” Charles said. “It’s up to us to wake it up.”

According to Elder, the team’s documentaries are also popular with indigenous audiences outside Alaska, including the Navajo and Hopi of the Southwest, and Polynesian groups.

Clips of videos also play in the Museum of the North’s Gallery of Alaska, next to exhibits depicting artifacts from Southwest Alaska.

“The intention was to show that these aren’t just some dusty things in a museum but part of someone’s culture,” said Kamerling.

In 2006, “Drums of Winter” was one of 25 films added to the National Film Registry. This prestigious honor led to funding opportunities from the National Film Preservation Foundation and Rasmuson Foundation to do a digital, scene-by-scene restoration of the film. With the help of Bob Curtis-Johnson, a film preservationist in Anchorage, the team also produced new duplicates of the film that will never be shown.

Kamerling and Elder hope to replicate the undertaking for the rest of their Alaska documentary collection.

“For film preservation, film is the only thing we know will last a hundred years or more if taken care of,” Kamerling said. “We don’t know that about everything else.”

But the process is expensive and laborious. According to Kamerling, restoring and preserving “Drums of Winter” took more than a year.

While the best way to preserve a film is to copy it onto another length of film, Elder said that many people will resort to making a digital master — with the hope that someone else comes along and remasters those films once the digital technology becomes obsolete.

But no matter what process they choose, leaving the films to time is a nonstarter.

“We’re not ready to die until we get all the films remastered and all the audio remastered,” Elder said.