Denmark finishes application to make ancient Greenland hunting ground a UNESCO World Heritage Site

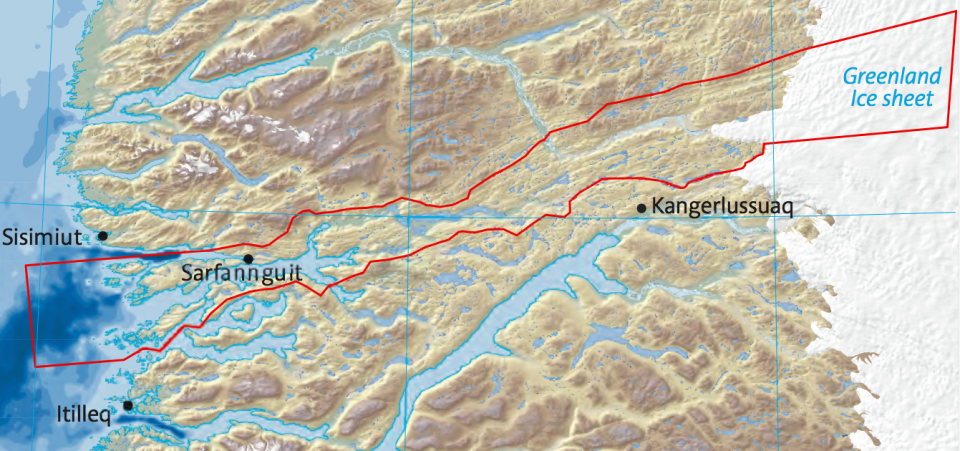

Denmark has undertaken the final step in the process of applying for World Heritage Site status for a 4,000-square-kilometer (more than 1,500-square-mile) swathe of land just north of the Arctic Circle, stretching from Greenland’s icecap, to Baffin Bay.

The area, known as Aasivissuit-Nipisat, was first used by Paleo-Eskimos around 2150 B.C., followed by successive cultures – including Saqqaq, Dorset and Thule – and first went out of use in the 1950s, when increasing modernisation led to the end seasonal migration.

In addition to its natural beauty, the site, according to the application, is worth recognition because it includes remains that “testify to the annual cycle and the conditions which were so special for the Greenland hunter culture.”

Those remains show clearly that hunters living in the area spent winters along the coast, where they hunted marine mammals, including whale, walrus and seal, before moving to encampments along inland fjords and streams to conduct spring trout-fishing.

In late summer, they moved further inland to hunting grounds where they carried out organised reindeer hunts that involved the use of inussuk cairns as a form of scare-crow to steer reindeer towards traps.

It is up to UNESCO, the UN cultural agency, to evaluate whether Aasivissuit-Nipisat is significant enough for the history of human development that it can be designated a World Heritage Site. Once a site is listed, countries are required by international treaty to protect it for future generations.

Of the 1,052 World Heritage Sites, 16 are in the greater Arctic. Given its size and variety of wildlife and cultures, the region, conservation groups have suggested this is too few. In order to close the gap, and to help protect the region’s environment, the IUCN, a Switzerland-based NGO, proposed last year a list of 12 maritime areas it believes ought to be considered. Before that, a 2007 report looked at ways to ensure the region had its fair share of sites.

In addition to conservation, Danish and Greenlandic authorities also see World Heritage designation of sites in the Kingdom of Denmark as an economic opportunity.

In Greenland, for example, Ilulissat Icefjord, which became a World Heritage Site in 2004, is the country’s leading tourism destination, and draws heavily on its status in its marketing efforts. Local officials said they hoped being named a World Heritage Site would also lead to more visitors to Aasivissuit-Nipisat.

The area is fortunately placed for this to happen. Kangerlussuaq, Greenland’s main international airport for the time being, and a busy cruise-ship port, is located at the southeastern corner of the proposed area. Sisimiut, the country’s second largest city, lies outside the north-western boundary.

The two towns are linked by a 200-kilometer trail, and plans to build a two-lane gravel road, Greenland’s first road connecting two settlements, has long been discussed, by are stranded due to a lack of funding and uncertainty about Kangerlussuaq Airport’s future.

The next important phase in the selection process will come this summer, when a team of UNESCO inspectors visits Aasivissuit-Nipisat. Their decision is expected in 2018.

Another Greenlandic site, the Kujataa Viking farming settlement in southern Greenland, has been reviewed by UNESCO. A decision about whether it will be added as a World Heritage Site is expected this summer.