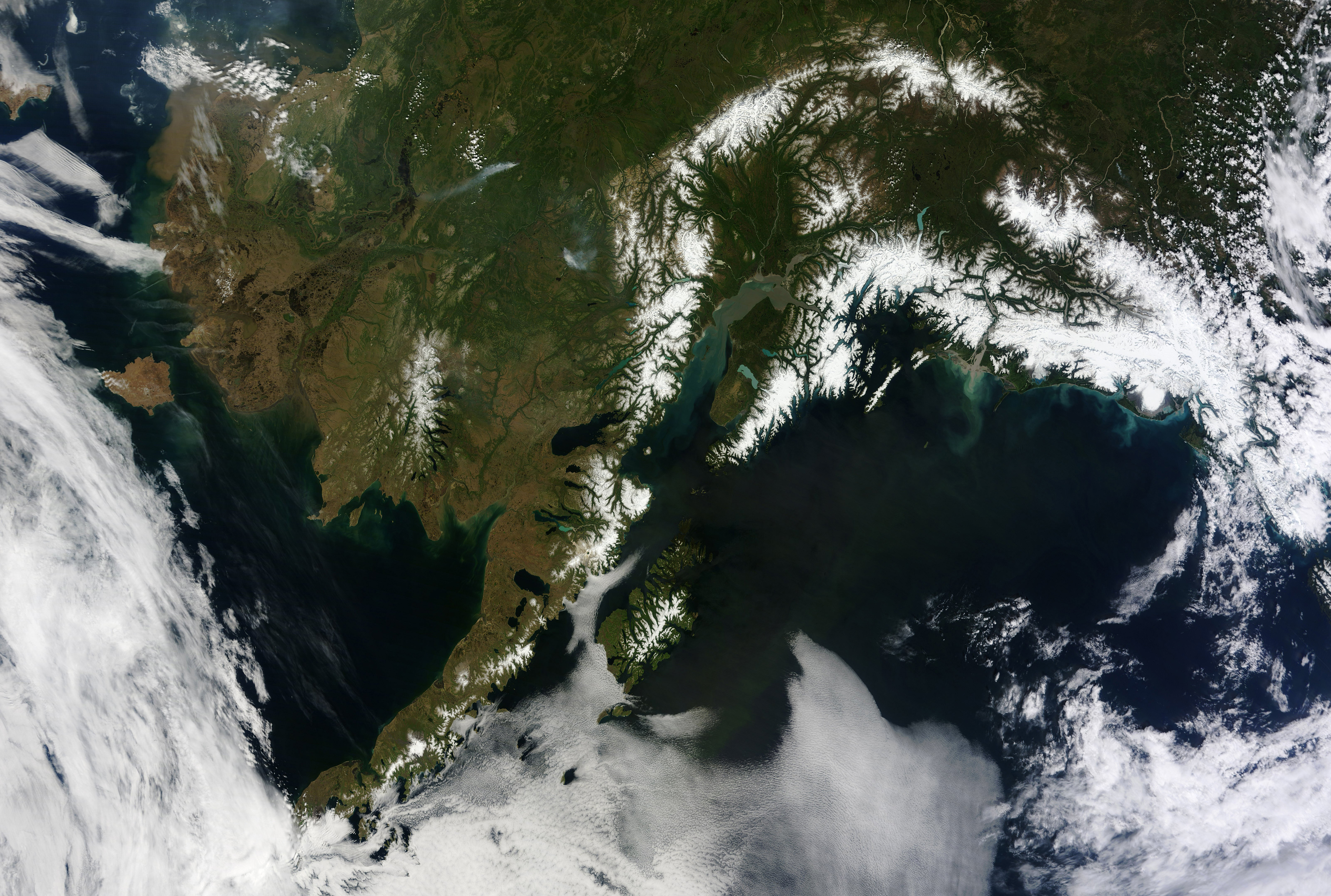

Does the ‘Blob’ foretell the North Pacific’s future? A scientist says yes.

There is good news and bad news about the big warm-water “Blob” that has wreaked havoc on the North Pacific for the past three years, an expert told fellow scientists at the Alaska Marine Science Symposium in Anchorage.

The good news: The unusual warm conditions that have persisted in the waters off Alaska and the West Coast now appear to be diminishing, said the climatologist who named the water mass the “Blob.” Seasonal forecasts are calling for only a slightly warmer-than-normal Gulf of Alaska for next summer, “suggesting this event is winding down,” said research meteorologist Nick Bond of the University of Washington. “So I think that’s good news for many aspects of the ecosystem.”

The bad news: The higher temperatures that emerged at the end of 2013 and seemed so remarkable could become the norm in future decades.

If carbon emissions continue on their current path, average April-to-June sea-surface temperatures in the second half of this century are expected to be 3.2 degrees Celsius (5.8 degrees Fahrenheit) higher in the Gulf of Alaska than they were in the second half of the 20th century, said Bond, who also serves as the Washington state climatologist.

In the Bering Sea, where sea ice is expected to disappear even in winter, average sea-surface temperatures in summer are expected to be 4 degrees Celsius (7.2 degrees Fahrenheit) higher than they were in the second half of the 20th century with those carbon emissions, Bond told the symposium audience.

“You can see that (these kinds) of sustained temperature increases are going to be even greater than what we just experienced here with this event,” he said.

The unusually warm waters in the North Pacific are believed to be linked to a series of animal illnesses and deaths, big algal blooms and marine oddities over the past few years.

Dozens of large whales were found dead in 2015 and 2016 in the Gulf of Alaska, an occurrence that federal regulators formally designated as an “unexplained mortality event” warranting detailed examination.

Tens of thousands of dead common murres have been found since last spring on Gulf of Alaska beaches — and in unusual inland areas — in what is believed to be the biggest die-off of that species.

An unprecedented die-off of tufted puffins was discovered this past fall when more than 200 emaciated carcasses washed up on St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea.

Sea otters in Kachemak Bay were found sick or dead in 2015 from what appeared to be algal-produced toxins; misshapen and dead sea stars were also found that year in Kachemak Bay, a site once thought to be too cold to harbor the wasting disease that has been killing sea stars in more southern waters.

Problems emerged all the way down the West Coast; thousands of starving sea lion pups have turned up stranded on the California coast, prompting another unusual mortality event designation.

The warm water believed to be linked to these ecosystem problems was not just at the top layer of the sea, Bond said. It reached about 80 meters in depth off Alaska and 200 meters in some spots off the West Coast, he said.

“These warm temperatures weren’t just a thin puddle of water right near the surface,” he said.

The Blob was not the direct product of climate change, Bond said. The warm conditions resulted from a series of unusual weather patterns, including a high-pressure system over the West Coast that blocked storms and winds one year and a low-pressure system another year that brought warm air into coastal Alaska, he said. “That’s why we’re calling it a climate event. It’s not a slow warmup like we’re going to see and are seeing with climate change,” he said.

But the long-term warmup is likely to make the climate event of the past three years a preview of what is to come in future decades, he said. “This recent one is kind of going to be more typical of what conditions are going to be in the ’40s and ’50s,” he said.